Principle 7: Living locally – A `20 minute` city

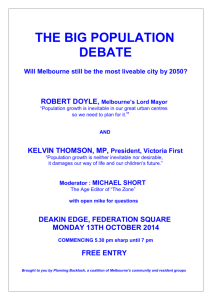

advertisement

7 Principle 7: Living locally – A ‘20 minute’ city Accessible, safe and attractive local areas where people can meet most of their needs will help make Melbourne a healthier, more inclusive city. Having a range of services close to home and work frees people up to do more of the things they enjoy. By ‘locally’ the Committee means travel distances of 20 minutes as rule of thumb. Living locally can be achieved by adding services (and the population to support those services) to existing areas and improving transport connections (especially walking, cycling and local buses) to existing services and jobs. It is at the local level that the Strategy can deliver choice and opportunity to people. The first five principles identified a number of implications for how local areas could be managed: ›› provide places and shared public environments to foster social contact including transforming roads that no longer carry as much traffic into more attractive urban places ›› support local services, local clubs, organisations and networks ›› provide settings for artistic, cultural and sporting endeavours ›› address affordable living ›› promote innovation in design and construction ›› support a variety of housing needs at a local level ›› establish Melbourne and Victoria as leaders in building environmental resilience into urban areas ›› promote the retrofitting and re-engineering of Melbourne’s existing suburbs – reducing energy use, water use and waste production. As our population ages, and household structures change, our social, educational, recreational and health needs also change. If services are to be delivered to areas where they are most needed in the future – rather than where they were most needed in the past – the infrastructure required to deliver these services must also change. Key issues raised in research and consultation Can living locally be achieved? A number of people the Committee spoke to thought that a ‘20 minute city’ might be an aspirational goal that could not be achieved in reality. The range of services available within a 20 minute walk is much less than a 20 minute drive. We recognise that in some areas achieving this principle will require more change than in other areas, but we think this principle can be achieved by locating new housing close to services and jobs, improving the delivery of services, and improving local accessibility. Whether the 20 minute travel distance is by walking, cycling, bus or car will depend on the area and the habits of its residents. Better services and cheaper travel alternatives will provide more choices for residents. Different people have different needs Creating a 20 minute city will mean different things at different life stages: the needs of young families will be different to the needs of the elderly. The 20 minute city means distributing services, facilities, jobs, education and entertainment across Melbourne’s suburbs so they are accessible. It does not mean creating an artificial hierarchy of local centres. Uses may be clustered in certain places but the 20 minutes should be measured from the front door to a number of locations (and these locations could differ from neighbour to neighbour), rather than from one central node outwards. This is a departure from the way planning has occurred in the past but is achievable. 64 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper ST KILDA ROAD APARTMENTS source: DEPARTMENT OF PLANNING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT In the past six years, one in 20 new dwellings in established areas of Melbourne have been constructed within 600 metres of the Route 8 tram, which travels from Moreland to Toorak. Are we providing enough land for sub-regional employment hubs? 65 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper Principle 7: Living locally – A ‘20 minute’ city Some areas have obvious potential Much of inner Melbourne most likely already delivers a ‘20 minute city’. The real challenge we see is how the middle and outer suburbs of Melbourne can be adapted to provide more services closer to people, and better access to those services that are already there. A number of councils have plans to bring more jobs and better services to their residents. These councils observe that the ‘choice rich’ areas of the middle and inner eastern suburbs serve as a good model for a pattern of development that provides a range of facilities in a diverse range of locations, with good access for residents. Housing supply and local areas The Strategy must develop some ideas about how to get more diverse housing in more locations at a reasonable price in established areas of Melbourne. The Central City is growing about as fast as the growth areas on the fringe. Within established areas, some suburbs are suitable for redevelopment and some are not, and only a relatively small proportion of land area would be required to accommodate a significant proportion of Melbourne’s growth. It costs an average of $131,400 more to build an ‘infill’ dwelling compared with a new subdivision in a growth area. Achieving more development in established areas would require a reduction in this price difference. The Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute’s (AHURI) recently published report ‘Delivering diverse and affordable housing on infill development sites’ identified barriers to infill development as well as suggestions to enable more diverse and affordable housing on infill development sites. Several of the AHURI’s ideas warrant consideration in the context of the new Strategy. Infrastructure in established areas A number of people expressed concerns about the capacity of infrastructure in established areas of Melbourne. A review of Melbourne’s utility infrastructure was undertaken to better understand current and future capacity. This work covered water supply, sewerage, stormwater drainage, electricity, gas and telecommunications. It was found that utility companies are generally satisfied that their infrastructure meets current capacity requirements, and while metropolitan Melbourne’s infrastructure may experience localised constraints as development progresses, in general, utility companies are wellplaced to complete planning and mitigation measures as required. Ideas and aspirations for change The Committee has identified three initial ideas for strategic priorities that might help make Melbourne a ’20 minute city’. Idea 8: Delivering jobs and services to outer area residents Services need to be provided in a more timely manner to urban growth areas and established outer areas of Melbourne. The problems of few jobs and a lack of services in these areas are complex, and solutions will require new ways of thinking to maximise growth opportunities and economic participation by residents in outer urban areas. Melbourne has developed an efficient development industry for delivering housing and shops to growth areas but we have not delivered enough local jobs to support this housing. In some places this 66 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper New employment opportunities in a growth area - Melton ShiRe CounCil - ABOuT ThiS REPORT This Annual Report documents Melton Shire Council’s performance over the 2010/2011 financial year. It meets our obligations under Section 131 of the Local Government Act 1989 (Vic) and provides information on performance against the 2010/2011 Annual Plan and Budget. SOURCE:GROWTH AREAS AUTHORITY CAROLine SPRINGS civic centre library SOURCE: MELTON SHIRE COUNCIL Melton Shire Council - Annual Report 2010/11 - 3 67 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper Principle 7: Living locally – A ‘20 minute’ city is because land has not been set aside for employment – no land was identified for industrial uses or activity centres did not provide land for local offices and employment. Employment uses might not be viable on ‘day one’ but recent and past experience shows that as the community matures the demand for local office and employment spaces rises, especially in the service sector. While there is debate about what the future demand for employment in outer areas will be, there is concern that poor planning stifles the early growth of jobs rather than it being a fundamental lack of demand. Planning for new areas needs to be seen as more than urban design and traditional land use planning and needs to involve stronger partnership between government and developers to support the growth of viable local communities. This approach could consider active programs for attracting jobs. Not all jobs for growth area residents will be provided in growth areas themselves. Some employment might be better encouraged towards existing middle and outer areas of Melbourne that are convenient to growth areas. An overall vision for the economic development of middle and outer areas needs to be developed. For example, in Melbourne’s west a new university and regional hospital could anchor new jobs although these may require government investment. The Outer Metropolitan Ring transport corridor and the Regional Rail Link project provide opportunities for jobs growth in highly accessible locations around stations and interchanges. Employment areas should be considered for locations around key interchanges along the Outer Metropolitan Ring corridor. Local planning policies and zoning reforms could encourage new neighbourhood centres and small supermarkets to ‘fill the gaps’ in existing networks, and help bring services closer to people. Bringing local services closer to people requires more flexibility and creativity at a local planning level. Small urban renewal sites, such as transitioning industrial sites in inner and middle suburbs, may present opportunities to provide more local services. Idea 9: Providing diverse housing in the right locations at a reasonable price The debate about infill housing in Melbourne must move beyond the impact of villa units on suburban streets and address how we can deliver different types of housing, in the right locations, at a reasonable price. Neighbourhood character is certainly important and areas identified as having valued characteristics should be protected. However, neighbourhoods that are in need of, and will benefit from, urban regeneration, as well as former industrial areas suitable for renewal should also be identified. The real issue in housing is this: how does Melbourne ensure its citizens have access to appropriate housing at an affordable price that supports affordable living? A key aspiration could be to create, over the next 10 years, a housing model that can deliver a three bedroom townhouse or apartment in the middle suburbs that is affordable to a median income household. The Committee was told this would mean reducing the price of such a dwelling by at least $100,000. Local area planning could support a mix of uses in new developments – for example, a ‘vertical village’ where a number of land uses are delivered in the one building (even three or four storey buildings) and not just apartments. There is a need to better target areas for more diverse housing development, to identify the type of dwellings needed to cater for local housing needs, and to develop clear criteria for selecting locations for medium or higher density housing. There is also a need to devise appropriate 68 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper Figure 13: The benefits of trees Reinforces sense of place and city identity Improves community cohesion Reduces sun exposure providing shade and cooling Enables energy savings Enables health savings Reduces air pollution Provides habitat and greater biodiversity Encourages outdoor activity Reconnects children with nature Reduces heat-related illnesses Reduces flows and nutrients in stormwater Improves mental wellbeing Increases property values Assists in carbon trading Avoids costs of infrastructure damage SOURCE: adapted from the woodland trust, uk Instead of a costly upgrade to the Ringwood Main Sewer to reduce spills into Brushy Creek after heavy rains, a series of smaller interventions across the catchment will achieve a better environmental outcome at a lower cost. What are your ideas for creating the 20 minute city? 69 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper Principle 7: Living locally – A ‘20 minute’ city planning tools to deliver more affordable and diverse housing choices. Even if housing affordability is dramatically improved, there will still be a need for more effort to deliver social housing, and below market price housing, across a range of locations. This will be needed to avoid concentrations of disadvantage, and in some more expensive areas to ensure that ‘key workers’ – such as police officers, nurses, teachers – can afford to live locally. A cooperative approach is required to plan for higher density development. Simply put, councils as a regional group, need to work with their communities to identify enough opportunities to cater for more diversity of housing types in established areas. Developing a process that can properly balance the aspirations of different local communities with State Government concerns about housing supply and infrastructure investment will require partnership and leadership. Idea 10: Improving the environmental performance of suburbs Melbourne is a suburban city and that will not change. The environmental performance of its suburbs can be dramatically improved. With a likely increase in distributed energy systems, and the need to address environmental issues across metropolitan Melbourne, local areas can be the focus for efforts on making Melbourne more environmentally resilient. While individuals can act to address the sustainability of their own houses, encouraging a neighbourhood approach to sustainability has the potential to make the process easier and more effective. A host of small-scale interventions can help avoid the need for large infrastructure investment. For example, rainwater tanks can help reduce the need for new water mains. Improving the energy efficiency of existing houses will require retrofitting and renovation. This process will be improved by shared knowledge in the community about how this is best achieved and a local building industry that is familiar with the challenges this presents in their local area. Initiatives such as local energy generation need to be planned as part of renewal or redevelopment processes. Waste recycling programs and area-wide tree planting need to be tackled on a neighbourhood basis. Better use of stormwater and stormwater treatment requires an area-wide approach as does the introduction of a ‘third pipe’ for recycled water supply. Trees are highly valued in Melbourne’s suburbs. The tree canopy of the city could be increased with significant environmental and aesthetic benefits. Melbourne could increase tree cover in parkland and along waterways and by planting more street trees, including fruit bearing trees, throughout its neighbourhoods. A program of ‘green neighbourhoods’ could help address all aspects of sustainability. Much of this effort could be community-based, with activities to bring people of diverse ages, ethnicities, abilities and life stages together. Already the greatest take-up of solar panels is in the middle suburbs. This positive trend could be extended beyond individual houses to the development of community programs. 70 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper 71 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper 5 Making it happen The Metropolitan Planning Strategy must move away from regulation as the primary means of achieving planning outcomes. Instead, we need to invest more heavily in vital infrastructure to support city growth and social cohesion, and foster stronger partnerships between government, the private sector and the community. It is important that the community endorses the Strategy and expects successive state governments and councils to work toward its delivery. Private development can often recognise opportunities government has not considered and systems should be established to better respond to these initiatives. The planning system needs to be flexible and responsive to changing ideas, business practices, and living preferences. The final two principles outline how the Strategy could be implemented. Principle 8 - Infrastructure investment that supports city growth Principle 9 - Leadership and partnership 72 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper FIGURE 14: investment in transport infrastructure declined 1970–2001 3.5% Transport infrastructure investment as a proportion of GDP 3.0% 2.5% 2.0% 1.5% 1.0% 0.5% 0.0% 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 Source: abs, 2002; asna, cat no. 5204.0, abs NOTE: transport and storage gross fixeD capital formation as a proportion of gdp (1970-2011) FIGURE 15: Major city shaping projects identified in victoria’s 2012 submission to infrastructure australia Project Description East West Link Construction of a freeway-standard link connecting the Eastern Freeway to CityLink, the Port of Melbourne and to the M80 Ring Road Melbourne Metro Construction of a nine-kilometre rail tunnel between South Kensington and South Yarra, including five new stations at Arden, Parkville, CBD North, CBD South and Domain and improved services across a broader area Port of Hastings Planning for and construction of the Port of Hastings as an international container port, including planning for transport links such as the Western Port Highway Dandenong Rail Capacity Program Staged construction of a series of projects along the Dandenong Rail Corridor, including priority grade separations, signalling upgrades and platform lengthening to allow the running of high-capacity trains Western Interstate Freight Terminal Construction of an interstate freight terminal and freight precinct in Melbourne’s west at Truganina, including a standard gauge rail link to the interstate rail line M80 Upgrade Completion of the staged upgrade to the M80 Ring Road between Laverton North and Greensborough Source: VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT, 2012 73 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper 8 Principle 8: Infrastructure investment that supports city growth A single integrated land use, transport and social infrastructure strategy means ensuring that infrastructure investment supports sustainable land use patterns and drives productivity. The type, quality and capacity of urban infrastructure influences how well a city performs economically and the opportunities and capabilities of its citizens. Infrastructure is not simply roads and railway lines, ports, airports, pipes and cables. It also includes social and community infrastructure such as schools, health and welfare facilities, sports facilities and learning hubs. Infrastructure needs to be provided to Melbourne’s growing suburbs in a timely manner. The cost of servicing needs to be considered when identifying areas for development. Leveraging urban renewal and development off existing infrastructure and transport investment makes infrastructure provision more effective, efficient and affordable. The nature and location of Melbourne’s infrastructure requirements will change over time. The amount of infrastructure we need depends on how we behave. For example, the demand for water is less now due to changes in people’s attitudes and behaviour. Comprehensive planning and evaluation processes are required to prioritise competing demands. We must optimise the use of existing infrastructure to take full advantage of its value. Key issues raised in research and consultation Historic under-investment The provision and maintenance of infrastructure and services, particularly on Melbourne’s urban fringe, has lagged behind population growth for some years. Reductions in expenditure have contributed to a substantial transport backlog, increased traffic congestion and peak crowding on trains and trams. It is expected that we follow the broad Australian trend. Figure 14 shows the reduction in the share of Gross Domestic Product spent on transport infrastructure over time. Shaping the city The lack of an Infrastructure Development Plan is seen as a major shortcoming of ‘Melbourne 2030’ – the strategy for metropolitan Melbourne adopted in 2002. Commonwealth funding will be needed to help deliver required infrastructure, particularly transport infrastructure. The key transport projects needed in Melbourne are of national economic significance, justifying Commonwealth funding. The Victorian Coalition Government has developed plans for a number of major infrastructure projects and has made submissions for funding to Infrastructure Australia for possible Commonwealth funding. Smaller infrastructure projects – such as a program of bus priority works – may possibly have a better cost-benefit ratio than some larger projects. Working infrastructure harder In a budget-constrained environment Melbourne needs to get the most value from its existing services and infrastructure. This applies to all infrastructure, from community and health facilities to transport. A critical shift in thinking is to measure the efficiency of roads by the number of people or the amount of goods they move, rather than the number of vehicles. The SmartRoads Program is addressing these issues. A more creative approach to managing roads – for example, by reconfiguring two parallel roads to a pair of one way roads – could free up road space improvements for public amenity and allow trams to have a dedicated reservation. 74 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper southern cross station SOURCE: Public transport victoria Average tram speeds in Melbourne are 16 kilometres per hour. However, they are as high as 25 kilometres per hour where trams are separated from other traffic. Increasing the average tram speed across the network to 21 kilometres per hour could eliminate the need to buy just over 60 trams (and build associated infrastructure), saving about $600 million. How can we unlock the capacity of our existing urban infrastructure? 75 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper Principle 8: Infrastructure investment that supports city growth Some public transport services are constrained by outdated technology such as signalling systems, road congestion and service design. Making better use of existing rail infrastructure by reviewing land use planning around key railway stations could help to maximise the strong investment that has been made in this important infrastructure. Looking to the fringe One of Melbourne’s challenges is the lag in infrastructure provision on the city fringe that limits employment, community services and social opportunities for people living in these areas. Some councils want to slow the rate of development to better align with infrastructure and service delivery. Others see high growth as a leveraging opportunity for increased infrastructure and services funding. There is a need to ensure education opportunities, at all levels, are spread across Melbourne to conveniently serve citizens and provide social, health, recreational and public transport services in a timely manner to growth areas. Many community and charitable organisations cannot provide services in growth areas because of a lack of local accommodation. Providing service hubs that can house community and charitable organisations, when an area is being developed, would help address this problem. Who should pay for infrastructure? More infrastructure will be required to meet the needs of a growing Melbourne, and this will require hard choices and political leadership. All levels of government can assist in the development and funding of infrastructure programs. Better funding of maintenance and operation of existing infrastructure is also required. The State Government’s average expenditure on infrastructure over five years to 2015–16 will be 1.4 per cent of Gross State Product. This is more than the 1.3 per cent recommended by the Independent Review of State Finances. But this alone will not address the backlog and growing needs of Melbourne. If Melbourne is to deliver much-needed infrastructure at a faster rate, it may need to explore a range of alternative funding sources. Decisions about how new infrastructure is funded can affect when that infrastructure is delivered and who has access to it. A number of issues need to be considered: ›› ›› ›› ›› ›› ›› the benefits of more timely delivery of much-needed infrastructure efficient use of infrastructure efficient use of government funds equity – is there a fair distribution of benefits and charges on households community attitudes the economic and administrative feasibility of collection. New sources of funds could increase investment, send better price signals to the market, influence people’s behaviour in beneficial ways, and facilitate public-private partnerships. Possible funding mechanisms include: ›› ›› ›› ›› development contribution charges user pays and beneficiary pays assets sales such as surplus government land or infrastructure assets value capture including special or differential rates. 76 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper FIGURE 16: Planning scheme reserves from 1968 and built freewayS and parks SOURCE: land victoria CURRENT AERIAL of Melbourne looking south SOURCE: Department of planning and community development 77 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper Principle 8: Infrastructure investment that supports city growth Having determined how infrastructure is to be funded there is also a need to determine how it will be financed. The Growth Area Infrastructure Contribution (GAIC) applies to growth area land brought inside the Melbourne Urban Growth Boundary or within a growth area zoned for urban development. The GAIC is used to help fund State Government infrastructure and is applied uniformly to eligible land on a per hectare basis. Recently the Victorian Coalition Government has moved to provide for a ‘Works in Kind’ model to see the early delivery of State infrastructure projects. This is one example of how changes to current funding systems can facilitate infrastructure provision. Current planning provisions allow councils (and the Government) to introduce Development Contribution Plans so that developers pay for certain infrastructure. Development Contribution Plans are widely used in growth areas but could be better designed to apply in ‘infill’ locations. In NSW and other jurisdictions, contributions are required from different types of development across the whole of the municipality without the need to apply local provisions. A review of the Victorian development contribution system is underway. The review will develop a new ‘off the shelf’ model for local development contributions and set up a range of standard schedules for different development settings across Victoria. Most infrastructure has some form of user charge. We all pay for water, telephones and power. But unless we travel on one of Melbourne’s tolled freeways we do not pay directly for road use. The mix of tolled and untolled roads in Melbourne does not derive from any explicit policy about how roads ought to be managed and therefore can create inefficient travel patterns and inequities as to who pays and who doesn’t pay. Any recourse to a new revenue stream or increased return from an existing stream will be easier to implement with community support. Such support is often higher when the revenue is earmarked for a particular purpose – a process called ‘hypothecation’. Rezoning or infrastructure investment can raise the value of land. This increase can be ‘captured’ directly by broadening the scope of infrastructure projects to include a land development component, or indirectly by differential rates on the increase in value that flows to the property owner. Finding the money Governments have a range of options for financing infrastructure if it is not paid for directly out of the budget: ›› borrowing ›› private equity or debt through public-private partnerships ›› project-specific bonds. Government bonds are a form of borrowing. However, they can be used to earmark borrowing for specific projects, providing a degree of transparency as to how the project is financed. The general desire to see a tight link between funding and delivery is illustrated by much higher community support for Government bonds compared to more general borrowing to fund infrastructure. Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) have been used for many years to deliver infrastructure and will continue to be an important means of delivering new infrastructure. Determining how to fund increased investment will involve identifying the most appropriate way to fund particular projects as part of the planning process. Facilitating the use of superannuation funds as a potential source of infrastructure funding could also be investigated. 78 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper the melbourne metro project could transform the Arden precinct SOURCE: arden-mcauley structure plan, city of melbourNe 79 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper Principle 8: Infrastructure investment that supports city growth Proper consideration should be given to providing greater flexibility for councils to source suitable funds to enable delivery of much-needed local services and facilities. Ideas and aspirations for change Infrastructure investment is critical to effective delivery of the Strategy. The Committee has identified three initial ideas to guide delivery. Idea 11: Using investment to transform places Major infrastructure investment results in transformative land use changes. In Melbourne, planning for major infrastructure investment needs to ensure that the best public outcomes – new jobs, housing choices, new open space and facilities – result from such projects and embed these in the delivery arrangements. Some major infrastructure projects will be delivered by public agencies and some by private firms. Regardless of how they are delivered, maximising positive, city-shaping effects needs to be a central concern from the outset of the project. Until recently cost-benefit studies for transport projects focused on travel time savings whereas some of the wider economic benefits can be more significant. These include giving people more choices about the places and people they can access, and supporting redevelopment of under-utilised areas. Idea 12: Moving to a place-based focus for programs In the past, many State Government programs have focused on meeting a specialised need or delivering one type of service. This has been the case for a range of projects, from transport to social services. There is a need to increase the focus on integrated place-based programs that focus on the needs of a particular area or community, instead of narrowlyconceived functional programs. Infrastructure Australia processes should foster this more integrated approach. The Committee sees a need to move thinking beyond individual projects, focused on narrow objectives, to a wider focus on a series of desirable outcomes. This means, for example, a grade separation project for a rail crossing could also involve an urban development component that aims to improve the public realm. Such projects require agencies to work beyond their usual scope or in partnership with each other and the private sector. Bundling a number of projects together might make them more attractive for private investment. Idea 13: Identifying a long-term framework for metropolitan infrastructure We need a long-term framework for metropolitan infrastructure that includes transport, community, health, education, recreation and open space, and utilities. This framework should reinforce achievement of the Strategy and address how infrastructure will respond to a changing climate. How we manage waste, and whether we continue to view it as waste or another resource, also needs to be considered. A works program needs to be developed as part of the metropolitan infrastructure framework. This would need to be flexible and not act as a handbrake on investment. A three or four-year funding program would provide much-needed certainty while a 10-year program would encourage private sector and community initiatives. 80 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper map 14: VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT submission TO INFRASTRUCTURE AUSTRALIA 2 East West Link 5 3 Dandenong Rail Capacity Melbourne Airport Port of Hastings and Tran Western Interstate Freigh 1 Central Melbourne M80 Ring Road Melbourne Metro Monash 4 Long-Term Planning 1 2 3 4 5 Avalon Airport Doncaster Link Study Outer Metropolitan Rin Melbourne Airport Link Rowville Link Study North East Link Features Major Roads Railways Regional Rail Link (under Airports Shipping Ports 2 Urban Area SOURCE: Department of planning and community development, 2012 East West Link 5 3 Dandenong Rail Capacity Program Melbourne Airport Port of Hastings and Transport Corridor Western Interstate Freight Terminal 1 Central Melbourne M80 Ring Road Melbourne Metro Monash 4 Long-Term Planning 1 2 3 4 5 Doncaster Link Study Outer Metropolitan Ring and E6 Melbourne Airport Link Study Rowville Link Study North East Link Features Major Roads Railways Regional Rail Link (under construction) Airports Shipping Ports Urban Area 81 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper Principle 8: Infrastructure investment that supports city growth There appears to be a broad consensus on the type of transport infrastructure improvements needed over the life of the Strategy. An expanded Central City will require an increase in transport capacity for access to and movement within the city – this can only be achieved by public transport with cycling and walking playing increasing roles, and would involve: ›› moving to a metro style train system (where train lines run independently of each other) to build network capacity; ultimately this could mean not all trains pass through Flinders Street Station and new inner Melbourne rail tunnels such as Melbourne Metro are required ›› building a rail link to Melbourne Airport as a gateway to Melbourne, and as part of the development of an employment cluster ›› expanding the tram network and moving towards a light rail system ›› improved cycling paths and an improved public realm for pedestrians. In inner Melbourne: ›› retrofitting cycling and walking opportunities into existing areas ›› moving towards a light rail system, with traffic delays addressed by dedicated rights-of-way or priority treatments ›› improving road capacity for traffic bypassing the Central City, including the East West Link ›› investigating options for Hoddle Street that acknowledge its important traffic distribution and public transport roles. For global competitiveness: ›› providing an alternative east-west bypass link to the West Gate-M1 corridor for a more efficient freight and logistics system ›› supporting the growth of Avalon Airport for air freight in addition to passengers, and investigating options for a new airport to the south-east of Melbourne ›› developing new freight precincts and gateways as part of a more decentralised network, including: -- rail freight increases where possible -- exploring new longer term port development options in the west of Melbourne, in addition to possible development of the Port of Hastings in the medium term -- new and more efficient terminals in outer areas close to national and international trade routes – such as the Western Interstate Freight Terminal -- a connected network of freight corridors including the Outer Metropolitan Ring transport corridor and the East West Link. To unlock capacity in middle and outer suburbs an integrated program of transport improvements could include: ›› using buses as the backbone of new public transport routes, with priority given to: -- improved local services and orbital SmartBus services linked with rail -- better transport interchanges at stations and activity centres -- better service coordination -- progressive delivery of disability access -- removal of bottlenecks 82 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper SMARTBUS in MELBOURNE SOURCE: BUS AUSTRALIA What new opportunities for business, investment, public transport and housing would the East West Link provide? 83 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper Principle 8: Infrastructure investment that supports city growth ›› grade separating critical railway crossings to reduce road congestion and support high frequency train services ›› extending train and tram lines and services ›› retrofitting cycling and walking opportunities to existing areas ›› more targeted management of roads and other assets, using the SmartRoads approach, to achieve local amenity improvements ›› investigating water-based transport routes on Port Phillip and the Yarra River, possibly providing a new public transport service from Melbourne’s west to the Central City ›› building new connections across physical barriers such as creeks, rivers and railways to improve local connectivity for walking, cycling, cars and buses. The south-eastern suburbs of Melbourne have a strong grid of arterial roads, whereas the road network in the west is less interconnected. Improvements will be required over the life of the Strategy. An integrated program of new roads, public transport, cycling and walking improvements will be required in Melbourne’s growth areas, coordinated with the sequence of land development. This will include constructing the Outer Metropolitan Ring transport corridor. Bus Rapid Transit corridors could operate within designated future rail reservations until the rail network is extended to these areas. Planning should be undertaken to improve links to regional cities by: ›› ensuring sufficient road and rail capacity between regional cities and Melbourne, and between regional cities ›› reserving land for Very Fast Train services to regional Victoria and interstate. The East West Link would provide a new east-west cross city connection north of the Central City. It would close the gaps between the major metropolitan freeways to the east, west and north and provide a much needed alternative to the Monash-West Gate freeways, including the West Gate Bridge. The project would: ›› provide an east-west alternative: relieving pressure on the West Gate–M1 corridor, and providing an alternative to the West Gate Bridge ›› improve freight efficiency: catering for growth at the ports of Melbourne and Hastings and improving productivity by improving travel time reliability for freight ›› enhance Victoria’s competitive advantage: improving the output of key industry centres and supporting the knowledge precinct in Carlton and Parkville ›› cater for population and economic growth: servicing key growth areas, supporting urban renewal opportunities and catering for forecast increases in freight movement ›› alleviate congestion: completing missing links between freeways to alleviate congestion and ensure travel time reliability for families and freight ›› improve public transport services and liveability: relieving congestion on inner city streets, allowing prioritisation for on-road public transport and providing opportunities for sustainable urban development. 84 | Melbourne, let’s talk about the future: Discussion Paper