The Economic Benefits and Tourism Impact of Rails

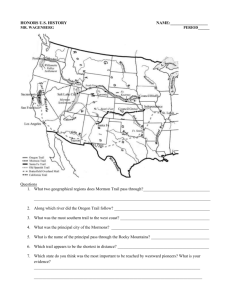

advertisement