Investing in the African electricity sector Ghana

advertisement

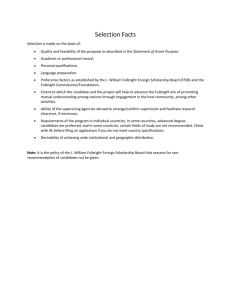

Financial institutions Energy Infrastructure, mining and commodities Transport Technology and innovation Life sciences and healthcare Investing in the African electricity sector Ghana Ten things to know Attorney advertising Investing in the African electricity sector – Ghana – ten things to know Investing in the African electricity sector – Ghana 01 | Why consider Ghana? The power sector in Ghana has approximately 2,443MW of installed capacity, of which a proportion is already provided by independent power producers (IPPs). Demand is predicted to exceed 5,000MW by 2016, primarily as a result of the Ministry of Energy’s objective of becoming a major exporter of electricity into the West Africa Power Pool, coupled with an increase in demand domestically, as the government seeks to increase the electrification rate to 80 per cent by 2016. This is further fuelled by a high annual GDP growth rate (14.4 per cent in 2011). The Government recognises the importance of IPPs to the achievement of these international and domestic expansion objectives. In terms of renewable energy projects, Ghana has wind and solar energy resources, as well as biomass and hydropower. Around 65 per cent of Ghana’s installed capacity is currently provided by the large-scale Akosombo and Kpong hydropower projects. Biomass also makes a significant contribution to the energy mix. The government is targeting to increase the contribution of wind and solar power to 10 per cent of the country’s capacity by 2020 and has recently enacted the Renewable Energy Law to support this objective. 02 | What is the structure of Ghana’s power sector? The Ministry of Energy is responsible for setting energy policy, including in the power sector. Prior to 2008, the Volta River Authority (VRA) was the state utility responsible for electricity generation, transmission and distribution throughout Ghana. The VRA is wholly owned by the Government of Ghana and was established in 1961 under the Volta River Development Act. Through its subsidiary company, the Northern Electricity Department (NED), the VRA remains responsible for (and is the sole distributor of) electricity in the northern regions of Ghana (being the Brong-Ahafo, Northern, Upper East, Upper West, and parts of Ashanti and Volta Regions of Ghana). As a result of the unbundling process completed in 2008, another state utility, the Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG), was established for the purpose of purchasing electricity from the VRA at a bulk tariff and distributing power in the southern regions. ECG is a private limited company that is wholly owned by the Government of Ghana. As part of power sector reforms implemented in 2005, the VRA’s mandate was restricted to electricity generation and the electricity transmission functions of VRA have been transferred to the Ghana Grid Company Limited (GridCo) 02 Norton Rose Fulbright (a process completed in 2008). GridCo is responsible for operation of the National Interconnected Transmission System (including dispatch), bulk power purchase of electricity from generators and sale to NED and ECG. It is also intended that the VRA’s distribution functions in the northern region of Ghana, currently vested in NED, will be transferred to the ECG, thereby creating a national distribution utility. Generators wishing to be connected to the transmission system must enter into an electrical connection agreement with GridCo. Ghana has two regulatory entities for the electricity sector. Generation licences are granted by the Energy Commission, which is also responsible for formulating electricity policy and rules governing the electricity sector, including a grid code. The Energy Commission is essentially a technical regulator. The Public Utilities Regulatory Commission (PURC) is responsible for the economic regulation of the electricity sector in Ghana (as well as gas and water), including the setting of tariffs. 03 | Does the Government participate in IPPs? The government has interests in most of the four IPPs in Ghana, indirectly, as a result of the participation of VRA or the Social Security and National Insurance Trust in the equity of the project. However the government’s main role in IPPs is as the power purchaser. Whilst VRA, GridCo and ECG all have the ability to purchase power from IPPs, none of them has sufficient covenant strength to facilitate the financing of a project where they are the offtaker without some form of government support. There is no consistent approach to providing government support for the IPPs that have been developed in Ghana to date. The issue has been approached in slightly different ways on two of the more recent IPPs for which power purchase agreements (PPAs) have been signed. In one case the Ministry of Energy entered into the PPA directly with the project company. In the other case the PPA was entered into by ECG and the Government of Ghana entered into a support agreement with the project company to augment the risk allocation and credit profile of the project. The Ministry of Energy has recently commented, in the context of renewable energy projects, that it is reluctant to provide government guarantees to support power projects. Instead it prefers developers to seek World Bank support Investing in the African electricity sector – Ghana – ten things to know in the form of MIGA/partial risk guarantees. It remains to be seen whether this signals a shift in policy and, if so, whether it is confined to the renewable sector or will apply to thermal power projects as well. 04 | How are tariffs established? Historically, one of the disincentives to private sector investment in power generation projects in Ghana was the prevailing level of tariffs, which were considered to be too low to be economic. This was partly due to the legacy by which the majority of Ghana’s power was generated by hydropower projects, as the costs per kilowatt hour are lower for hydropower than for a thermal power project. Tariffs have been increased on numerous occasions by PURC, with the aim of moving towards a more cost reflective tariff. However there is competing pressure to keep consumer tariffs as low as possible, which hampers the establishment of fully cost-reflective tariffs that would support IPPs. IPP developers have preferred to enter into power purchase agreements directly with the Government of Ghana or with the ECG, in order to establish an economic tariff. Notwithstanding this, the continued move towards costreflective tariffs by PURC will be a key factor in the growth of the IPP sector in Ghana. 05 | What are the fuel supply risks? Possibly the biggest constraint to the development of thermal IPPs in Ghana, as is the case in many emerging markets, is the availability of a reliable fuel supply. Take for example, the privately developed Sunon Asogli 560MW power plant at Tema. The project is a Ghanaian and Chinese joint venture which was not project financed and therefore not subject to the usual bankability requirements of a project financed IPP (such as a secure long-term fuel supply). Although construction of the first phase of the project was completed in mid-2009 it is not currently generating electricity, as it is reliant upon gas supply from the West African Gas Pipeline (WAGP). It had been anticipated that WAGP would play a major role in delivering Ghana’s energy security and is encouraging the development of gas fired IPPs. However, the supply of gas through WAGP has been repeatedly delayed or suspended through a combination of vandalism in Nigeria and other Nigerian supply constraints. It is unlikely that developers, lenders and indeed the Ghanaian government acting as offtaker would be willing to assume the supply risk that would be inherent in relying on the delivery of gas from WAGP until a regular and reliable supply of gas through WAGP is established. The only alternative supply of gas, being associated gas from the Jubilee field development in the West of Ghana, is unlikely to come on-stream for at least two years and is dependent upon the construction of suitable processing and pipeline infrastructure. The lack of a reliable gas supply has resulted in a number of existing power plants being configured to operate on both gas and liquid fuel, such as the 340MW Cenpower project in Tema and the nearby Kpone Project being developed by African Finance Corporation and Infraco. 06 | What is the typical risk allocation for IPPs in Ghana? As discussed earlier there is no standard form of PPA in the Ghanaian market. Nevertheless, the power sector is relatively small and the negotiation of new PPAs tends to be supervised from the government’s perspective by staff who have been involved in earlier PPA development and negotiations. Some of the PPAs that have been entered into to date have provided developers with a robust risk allocation that is in line with project finance norms for emerging markets. Therefore developers should be able to achieve a bankable risk allocation. The tariff structure under precedent PPAs in Ghana (which are for thermal plants) provides for the payment of capacity charges for dependable capacity and energy charges for electrical energy delivered. Fuel is sometimes tolled by the offtaker, therefore the need for fuel costs to be passed through the project company is avoided. However, a fuel adjustment payment/deduction is included to ensure that the project company takes the energy conversion risk. It has been customary for the government to accept responsibility and to provide revenue protection to the project company for risks typically classified as “political risks” (ie, by paying capacity charges on the basis of a deemed available capacity during periods when the project company (or offtaker, where applicable) is adversely affected by political risks). This includes risks such as war, civil commotion, expropriation, embargo, changes in law, etc. Whilst revenue protection is not provided for natural force majeure events (as is customary in project financed transactions in emerging markets), some PPAs provide for an extension to the term of the PPA that is sufficient to enable the project company to receive capacity charges that it was not able to earn as a result of a natural force majeure event together with any increased costs suffered as a result of such natural force majeure event. Norton Rose Fulbright 03 Investing in the African electricity sector – Ghana – ten things to know PPAs have also imposed a requirement on the offtaker to provide a stand-by letter of credit in an amount equal to three months’ capacity and energy payments on a revolving basis. This provides increased credit enhancement for projects. service costs and distributions of equity following the winding up of the business are freely convertible without restriction. An authorised dealer bank must be used to execute the conversion. 07 | What governmental approval is required for PPAs? 09 | What is the scope of a typical Ghanaian security package? Article 181(5) of the Ghanaian Constitution provides that any international business or economic transaction to which the State is a party requires parliamentary approval before it can become effective. Prior to May 2012 it was generally considered by Ghanaian lawyers, in the absence of judicial interpretation, that Article 181(5) applied to transactions to which the State and international companies were parties. Therefore, where the Government of Ghana contracted with a Ghanaian project company, albeit one that was majority owned by international sponsors, the general view was that such contracts did not constitute international business transactions and therefore parliamentary approval was not required for them to become effective. However, in the case of Attorney General v Balkan Energy Co. LLC (a project company supplying power generated by a power barge to the Government under a PPA), the Supreme Court of Ghana found that the PPA constituted an international business transaction for which Parliamentary approval was required but had not been obtained. As a result of the decision in the Balkan case, developers and investors are advised to obtain either: (a) Parliamentary approval for the transaction; or (b) certification by the Attorney General in respect of the particular transaction, post structuring of the transaction, to confirm that the substance of the transaction is not international and the transaction is an ordinary commercial transaction rather than a major transaction that could fall within Article 181(5) of the Constitution. It is possible that future legislation will clarify the scope of Article 181(5) of the Constitution. However, in the interim, developers and investors should take a cautious approach to ensuring that any contract with the Government is binding on the Government. In our experience the typical Ghanaian law security package on a project financed power project in Ghana has included: • legal mortgage over the land forming the site (which can also be granted over leasehold interests in land, including sub-leases which are commonly encountered, particularly on projects located in the Tema industrial area, as well as freehold interests); • fixed charges over movable assets, account balances, book debts, contractual rights, goodwill and intellectual property rights; • floating charge over the entire undertaking of the project company; and • a pledge of shares in the project company (usually a Ghanaian limited liability company). A legal mortgage is a registrable security interest under the Land Titles Registration Law 1982 (in the case of land situated in a registration district) and under the Land Registry Act 1960 (in the case of other land). It creates a right for the mortgagee to take possession and to obtain an order for the sale of the mortgaged property in the event that the mortgagor defaults on the loan secured by the mortgage. If a legal mortgage is not registered it will be void. Certificates of registration take a significant amount of time to be obtained, therefore the practice is for lenders to allow financial close to occur in reliance on evidence that the document creating the mortgage has been lodged for registration with the relevant registry. Ghana’s exchange controls were relaxed substantially in 2006, so that now it is only necessary for the repatriation of funds to be done by authorised dealer banks. These banks report foreign exchange transactions to the Bank of Ghana, but no exchange controls are imposed. Fixed and floating charges over assets of a company are subject to registration with the Registrar of Companies pursuant to the Companies Code 1963 and also with the Collateral Registry maintained by the Bank of Ghana under the Borrowers and Lenders Act 2008. Filing must be completed within 28 days of creation of the charge, failing which the charge will be void (and all monies secured by it become immediately due and payable). Businesses with foreign investment in Ghana are required to register with the Ghana Investment Promotion Centre, which guarantees that dividends, foreign debt A share pledge is created by an agreement requiring the chargee to deposit share certificates and an executed share transfer form with the chargor to enable the chargor to 08 | What protections do foreign investors receive? 04 Norton Rose Fulbright Investing in the African electricity sector – Ghana – ten things to know effect a transfer of the shares upon an enforcement event under the share pledge agreement. Share pledges must be registered with the Collateral Registry. The chargor should also serve notice on the company of its interest in the shares to ensure that the company is required to note the security interest in its register of members. Following notice, the company is prevented from registering any transfer of the secured shares without the chargor’s consent. Stamp duty is payable on any instrument executed in Ghana, or which relates to property in Ghana. Documents creating security over assets in Ghana are therefore subject to stamp duty. The rate of stamp duty varies, but can be up to 1 per cent of the value of the secured property. The effect of a failure to have a document stamped is that it cannot be used as evidence in any proceedings in Ghana and, in the case of a security document, it cannot be registered. projects (such as VRA’s 2MW solar PV plant that has been constructed in the north of Ghana). The lack of clarity on the level of the feed-in tariff and the determination of renewable energy procurement targets would appear to somewhat undermine the effectiveness of the Renewable Energy Act in the short term. Prepared by Norton Rose Fulbright LLP in conjunction with Oxford & Beaumont Solicitors (Ghana). Ghanaian law security can be held on trust for the secured finance parties. Enforcement of security is subject to a minimum 30 days waiting period pursuant to the Borrowers and Lenders Act 2008, following the expiry of which the security trustee can take possession of the charged asset and dispose of it without the need for court enforcement proceedings. 10 | Are incentives offered to renewable energy producers? The Renewable Energy Act 2011 introduces a feed-in tariff and provides for the establishment of a renewable energy fund which will be used to pay for the promotion and development of renewable energy sources as well as to fund the feed-in tariff. Ghana already has extensive hydropower and biomass generation capacity but it is intended that the Renewable Energy Act will stimulate a significant increase in the country’s solar, wind and biomass installed capacity. The Act provides renewable power producers with rights of grid access. The feed-in tariff levels are being established by PURC on the basis of, among other things, the technology and the installation costs. The Renewable Energy Act also imposes minimum renewable energy purchase quotas on the distribution companies, however the actual quantification of the quotas is under development by PURC. The government is looking to pay for the renewable energy fund through a mixture of a levy on biofuels exports, government money and EU funding. In addition to providing fiscal incentives, the fund will be used to pay for capacity building in the renewable energy sector, grid expansion and the development of technology and pilot Norton Rose Fulbright 05 Investing in the African electricity sector – Ghana – ten things to know Total package We have been active throughout Africa as legal advisers on transactions in the power sector for many years. Power generation and transmission projects are a core part of our business. We have extensive experience working with and advising sponsors, lenders, developers, bilateral and multilateral organisations and governments in Africa. We also advise on the regulatory changes which are being introduced in the energy sector of many African countries. More generally, teams from across Norton Rose Fulbright have worked on a wide range of project and trade financings, mergers and acquisitions, securities offerings, investment trusts, privatisations and dispute resolutions. Most of these transactions have involved substantial due diligence and extensive dealings with the relevant governmental authorities, companies concerned and local counsel. Accordingly, we are familiar with the requirements and structures usually sought by project sponsors, lenders and governments alike. Awards and accolades “This is a top firm – the lawyers have a reputation for being hands-on, and have an innovative and client facing approach.” Tier 1 Projects and Energy, Africa wide Chambers Global 2012 “They cover all asset classes and have exceptional strength in numbers.” Tier 1 Asset Finance, Global wide Chambers Global 2012 Tier 1 Projects and Energy, Power Chambers Global 2012 “The team has a real focus on climate change, and has invested hugely in it. ‘The firm is definitely up there when it comes to international emissions trading.’” Tier 1 Climate Change Law Firm of the Year City AM Awards 2012 Middle East & Africa Renewables Deal of the Year, Lesadi & Letatsi PV Project Finance Awards 2012 Chambers Global 2012 African Solar Deal of the Year, KSolar CPS Tier 2 Projects Project Finance Magazine 2012 Chambers Global 2012 African Renewables Deal of the Year, Addax Bioenergy Tier 2 Power Project Finance Magazine 2011 Legal 500 African Power Deal of the Year, Kivuwatt Tier 1 Banking and Finance: Project Finance, South Africa Project Finance Magazine 2011 IFLR 1000 2012 Rankings, awards and accolades included in this publication pre-date the combination of Norton Rose and Fulbright and Jaworski LLP on June 3, 2013. 06 Norton Rose Fulbright Investing in the African electricity sector – Ghana – ten things to know Contacts If you would like further information please contact: Beijing Tom Luckock Partner Norton Rose Fulbright LLP Tel +86 (10) 6535 3135 tom.luckock@nortonrosefulbright.com Cape Town Matt Ash Director Norton Rose Fulbright South Africa (incorporated as Deneys Reitz Inc) Tel +27 (0) 21 405 1200 matt.ash@nortonrosefulbright.com Dar es Salaam Adam Lovett Director Norton Rose Fulbright South Africa (incorporated as Deneys Reitz Inc) Tel +255 767 962 308 adam.lovett@nortonrosefulbright.com Durban Gary Rademeyer Director Norton Rose Fulbright South Africa (incorporated as Deneys Reitz Inc) Tel +27 (0)31 582 5810 gary.rademeyer@nortonrosefulbright.com Johannesburg Julian Jackson Director Norton Rose Fulbright South Africa (incorporated as Deneys Reitz Inc) Tel +27 (0) 11 685 8583 julian.jackson@nortonrosefulbright.com London Simon Currie Partner Norton Rose Fulbright LLP Tel +44 (0)20 7444 3402 simon.currie@nortonrosefulbright.com Madhavi Gosavi Partner Norton Rose Fulbright LLP Tel +44 (0)20 7444 3578 madhavi.gosavi@nortonrosefulbright.com Richard Metcalf Partner Norton Rose Fulbright LLP Tel +44 (0)20 7444 3482 richard.metcalf@nortonrosefulbright.com Bayo Odubeko Partner Norton Rose Fulbright LLP Tel +44 (0)20 7444 2745 bayo.odubeko@nortonrosefulbright.com Arun Velusami Partner Norton Rose Fulbright LLP Tel +44 (0)20 7444 2553 arun.velusami@nortonrosefulbright.com Charles Whitney Partner Norton Rose Fulbright LLP Tel +44 (0)20 7444 3171 charles.whitney@nortonrosefulbright.com Chris Down Senior associate Norton Rose Fulbright LLP Tel +44 (0)20 7444 5642 chris.down@nortonrosefulbright.com Paris/Casablanca Anne Lapierre Partner Norton Rose Fulbright LLP Tel +33 (0)1 56 59 5290/ +2126 0007 0060 anne.lapierre@nortonrosefulbright.com Arnaud Bélisaire Partner Norton Rose Fulbright LLP Tel +33 (0)1 56 59 52 17 arnaud.belisaire@nortonrosefulbright.com Poupak Bahamin Partner Norton Rose Fulbright LLP Tel +33 1 56 59 5438 poupak.bahamin@nortonrosefulbright.com Singapore Nick Merritt Partner Norton Rose Fulbright (Asia) LLP Tel +65 9618 3224 nick.merritt@nortonrosefulbright.com Tokyo George Gibson Partner Norton Rose Fulbright Gaikokuho Jimu Bengoshi Jimusho– Norton Rose Fulbright (Asia) LLP Tel +81 (0)3 5218 6823 george.gibson@nortonrosefulbright.com Norton Rose Fulbright 07 nortonrosefulbright.com Norton Rose Fulbright Norton Rose Fulbright is a global legal practice. We provide the world’s pre-eminent corporations and financial institutions with a full business law service. We have more than 3800 lawyers based in over 50 cities across Europe, the United States, Canada, Latin America, Asia, Australia, Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia. Recognized for our industry focus, we are strong across all the key industry sectors: financial institutions; energy; infrastructure, mining and commodities; transport; technology and innovation; and life sciences and healthcare. Wherever we are, we operate in accordance with our global business principles of quality, unity and integrity. We aim to provide the highest possible standard of legal service in each of our offices and to maintain that level of quality at every point of contact. Norton Rose Fulbright LLP, Norton Rose Fulbright Australia, Norton Rose Fulbright Canada LLP, Norton Rose Fulbright South Africa (incorporated as Deneys Reitz Inc) and Fulbright & Jaworski LLP, each of which is a separate legal entity, are members (‘the Norton Rose Fulbright members’) of Norton Rose Fulbright Verein, a Swiss Verein. Norton Rose Fulbright Verein helps coordinate the activities of the Norton Rose Fulbright members but does not itself provide legal services to clients. This publication was produced prior to June 3, 2013 when Fulbright & Jaworski LLP became a member of Norton Rose Fulbright Verein. References to ‘Norton Rose Fulbright’, ‘the law firm’, and ‘legal practice’ are to one or more of the Norton Rose Fulbright members or to one of their respective affiliates (together ‘Norton Rose Fulbright entity/entities’). No individual who is a member, partner, shareholder, director, employee or consultant of, in or to any Norton Rose Fulbright entity (whether or not such individual is described as a ‘partner’) accepts or assumes responsibility, or has any liability, to any person in respect of this communication. Any reference to a partner or director is to a member, employee or consultant with equivalent standing and qualifications of the relevant Norton Rose Fulbright entity. The purpose of this communication is to provide information as to developments in the law. It does not contain a full analysis of the law nor does it constitute an opinion of any Norton Rose Fulbright entity on the points of law discussed. You must take specific legal advice on any particular matter which concerns you. If you require any advice or further information, please speak to your usual contact at Norton Rose Fulbright. © Norton Rose Fulbright LLP NRF16189 06/13 (UK) Extracts may be copied provided their source is acknowledged.