Core Competencies for Health Care Interpreters Research Report

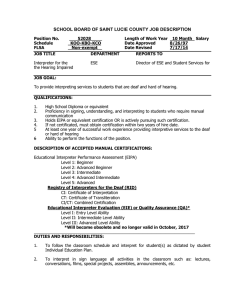

advertisement