Knowledge, Motivation, and Adaptive Behavior

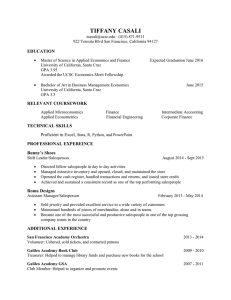

advertisement