Annual Report 2013-2014 - Child Death and Serious Injury Review

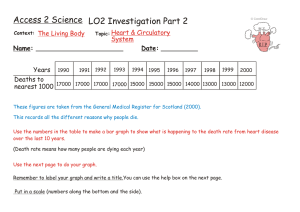

advertisement