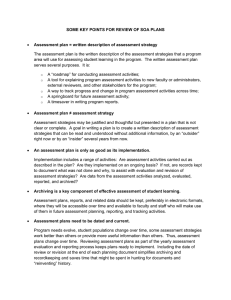

Archiving websites

advertisement