International Journal of Educational Research 48 (2009) 12–20

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

International Journal of Educational Research

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijedures

The effect of preschool dialogic reading on vocabulary among rural

Bangladeshi children

Aftab Opel a,*, Syeda Saadia Ameer a, Frances E. Aboud b

a

b

Early Childhood Development Resource Centre, BRAC University Institute of Educational Development, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Department of Psychology, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

A R T I C L E I N F O

A B S T R A C T

Article history:

Received 11 July 2007

Received in revised form 15 February 2008

Accepted 18 February 2009

The purpose of the study was to examine the efficacy of a 4-week dialogic reading

intervention with rural Bangladeshi preschoolers with the intention of increasing their

expressive vocabulary. Eighty preschoolers randomly selected from five preschools

participated in the 4-week program. Their expressive vocabulary, measured in terms of

definitions, was tested on 170 challenging words before and after the program and

compared with that of control children who participated in the regular language program.

Both groups were read in Bangla eight children’s storybooks with illustrations, but the

dialogic reading teacher was given a set of ‘‘wh’’ and definitional questions to enhance

children’s verbal participation. The mean vocabulary scores of dialogic program children

increased from 26% to 54% whereas the control children remained at the same level.

Results are discussed in terms of the successful application of dialogic reading to lowresource preschools.

ß 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Dialogic reading

Preschool

Expressive vocabulary

Bangladesh

1. Introduction

It is well-recognized that children from families who are poor and without formal education may not possess readiness

skills for primary school (Aboud, 2006; Britto & Kohen, 2005; San Francisco, Arias, Villers, & Snow, 2006). For example,

children from lower socioeconomic communities lag behind their counterparts on vocabulary and literacy skills (Evans,

2004). This is partly due to less responsive and sophisticated adult communication (Hoff, 2003) and less time being read

storybooks or hearing new stories in the early years (Raikes et al., 2006). The lack of exposure to story reading is particularly

problematic in countries such as Bangladesh where books are not available in rural areas and many parents are not literate

themselves. Although parents often tell stories to children under 3 years, this practice is discontinued once children reach

preschool age (Aboud, 2007).

Under these conditions, preschool teachers are relied on to provide the language stimulation necessary to develop

children’s pre-literacy skills such as vocabulary. Storybook reading provides exposure not only to literacy but also to unique

vocabulary not available from oral stories, in that storybooks connect children to words and situations beyond their village.

The frequency of book reading is known to be less important than what actually happens during the reading. Because the

current style of teacher–student verbal interaction has been unsuccessful in improving children’s vocabularies, we

implemented a program of group dialogic reading. The current study evaluated a 4-week intervention in rural Bangladeshi

preschools to improve children’s vocabulary using dialogic reading.

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: Aftab.Opel@gmail.com (A. Opel).

0883-0355/$ – see front matter ß 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2009.02.008

A. Opel et al. / International Journal of Educational Research 48 (2009) 12–20

13

1.1. Preschool situation in Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, preschools are still relatively new and their quality is the subject of extensive study. A recent survey in

Bangladesh showed that a total of 147 organizations, most of which are non-governmental, have preschool programs

attended by about 790,000 children (Early Childhood Development Resources Center, 2006). They are expanding rapidly and

considered essential in order to prepare children for primary school, reduce the drop-out rate, and increase the number of

children passing fifth grade competency tests.

Prior independent evaluations of preschools organized by non-governmental organizations indicated that in some

respects their quality was moderate—3.5 out of 7 on the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale (ECERS, Aboud, 2006).

Vocabulary scores on an adapted version of the WPPSI (Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence) were superior

to non-preschoolers with the same background, but still low. Because ECERS scores correlated significantly with children’s

school readiness and WPPSI reasoning scores (Matrices and Similarities), improvements to the program were guided by the

ECERS and recommendations of a child development specialist. The first round of improvements focused on activities and

program structure, rather than language and literacy. However, 50 storybooks were added to supplement the 10 currently

being used. Teachers were trained in how to be more responsive to children’s questions rather than predominantly offering

instruction to the whole group. However, offering free play with more complex and diverse learning materials was the major

thrust. After implementing these improvements, 10 preschools reached an average of between 4 and 5 on the 2 important

subscales of Activities and Program Structure (Moore, Akhter, & Aboud, 2008). This was accomplished within a year at

minimal extra cost.

Benefits were passed on to the children who attended the improved preschools in comparison to those who attended the

regular program, matched for ECERS score the year before. In particular, children showed greater improvements in Block

Design and Matrices, both measuring visual analytic reasoning that would later support math skills (Moore et al., 2008).

However, children’s expressive vocabularies did not increase much from the beginning to the end of the year in either group.

Action research using systematic written observations and conducted during the 7-month implementation of the improved

program indicated some limitations in the use of storybooks which could potentially impede children’s vocabulary gains. In

particular, the paraprofessional teachers were unable to talk about the events or characters in a way that went beyond the

text. Their questions required the group to give a yes/no response or repeat a phrase from the story. Consequently, the

children had little opportunity to use or expand their expressive language skills.

1.2. Dialogic reading research

A number of new language activities have been successfully tried elsewhere with children from 2 to 7 years of age to

improve their vocabulary. The rationale is that vocabulary is an important pre-reading skill associated with later reading

competence (e.g., Chow & McBride-Chang, 2003; Senechal, 2006; Snow, 2006). Oral vocabulary, both receptive and

expressive, is positively associated with reading competence at least through grade 4 and probably beyond (Storch &

Whitehurst, 2002). Vocabulary develops rapidly in the preschool years but there is wide individual variation: mothers’

reports reveal that 10-month-old children may comprehend anywhere from 11 to 154 words, and by the age of 6 it may

increase to 14,000 (Hoff, 2006). Systematic intervention in the pre-primary years is therefore important to increase

vocabulary in order to facilitate reading in primary school.

Many programs have been implemented with parents and teachers, including shared reading where the adult models the

strategies and skills of a proficient reader and the child assumes responsibilities in line with his or her increasing capabilities.

For a preschooler, this may mean engaging in the content or identifying words. The precise nature of these reading programs

is often based on descriptive evidence linking shared reading to vocabulary development. For example, children of 27

months had better vocabularies if their mothers asked questions, imitated their child, and related the story to the child’s

experience (Blake, Macdonald, Bayrami, Agosta, & Milian, 2006).

Among the interventions aimed at improving vocabulary, the one most suited to rural Bangladesh involves dialogic

storybook reading in the preschool context. Parents are unlikely to have books at home or to talk with children about pictures

in a way that extends vocabulary (Aboud, 2007). However, most preschool teachers have one 60-min language period every

morning with time for reading stories. Dialogic reading is a form of shared storybook reading in which the adult reader

engages the child(ren) in a verbal dialogue about the story as it is being read (e.g., Lonigan & Whitehurst, 1998; Whitehurst

et al., 1994). Children are actively engaged in expressive language when the teacher asks open-ended ‘‘wh’’ questions and

pursues the child’s answer with a further extension or question. Teachers thereby elicit talk about the story and children’s

related experiences, and also model sophisticated talk using the child’s output as a point of departure.

The dialogic procedure was successfully used in a 4-week program by Hargrave and Senechal (2000) to improve the

vocabularies of children 3–5 years who had lower vocabularies than expected for their age. As in the Whitehurst studies, the

teacher was trained with the help of a video and personal practice to ask ‘‘wh’’ questions, to follow the child’s answers with

questions, repeat the child’s answers, praise and encourage the child, and have fun. Extending the Whitehurst et al. (1994)

study where the procedure was implemented with groups of four 3-year-olds, Hargrave and Senechal read to larger

preschool groups of eight and compared them with groups of preschoolers read to in the usual shared manner. The parents of

children in each group were also asked to read provided books five times weekly in the same manner as the teacher (though

this was not always done). The dialogic reading group received higher scores on a test of expressive vocabulary especially on

14

A. Opel et al. / International Journal of Educational Research 48 (2009) 12–20

vocabulary from the 10 books. Expressive vocabulary was measured by picture naming because many of the children were

quite young. Still, the scores were low and the effect size was small.

The present study attempted to contribute to this line of work on reading and vocabulary development by examining the

benefits of dialogic reading in a developing country preschool program. Not only are the class sizes larger and the teachers

less trained, but the children are less familiar with books and with the encouragement to express themselves. Their low

vocabularies may be largely due to a verbally unresponsive environment. Furthermore, children’s storybooks are scarce so

making the most of each one with an extended dialogue might be an advantage in low-resource contexts. Consequently, we

examined the vocabulary benefits of a whole-class dialogic reading intervention in comparison to the regular style of shared

reading. Because putting thoughts into words is strongly encouraged in the dialogic reading procedure, its benefits may be

clearer when measured in terms of expressed definitions rather than naming pictures.

1.3. Objective and hypothesis

The goal of the present study was to examine improvements in expressive vocabulary of preschool children (5–6 years)

who participated in a teacher-implemented dialogic reading program in which eight books were read in Bangla over 4 weeks.

The control group of children attended preschools with the same basic program and were read the same books daily in their

usual manner. We expected the intervention group to show greater gains in expressed definitions than the control children.

2. Method

2.1. Design and sample size estimation

The design was a pre–post assessment of an intervention and control group. Using an alpha of .05 and power of .80, the

sample size was 80 per group to find a difference of .5 SD. Therefore there were 5 preschools per group with 16 children in

each school. Scientific and ethical approval of the protocol was provided by a review committee of academics and

researchers in this field convened by BRAC University’s Institute of Educational Development.

2.2. Preschool setting

Children were selected from 10 preschools in the rural sub-district of Kaligong in Bangladesh. Out of 41 preschools run by

Village Education Resource Centre, 5 were randomly selected to be intervention schools and 5 to be controls. The

organization had been operating early childhood programs since 1988 and recently began using the program and materials

provided by Save the Children, U.S. Thus, all their current learning materials, operating costs, and teacher training were

provided by Save the Children. In the usual program, teachers had a daily oral language period of 45–60 min during which to

read one of the provided stories and encourage expressive language. It was during this period that dialogic reading was

inserted in the sixth month of the school year. More details follow.

The education attainment of the preschool teachers, who usually came from the village, ranged from grade 10 to 12. They

received 1 week of training in early childhood education at the beginning of the school year and 1 day each month on how to

implement the lesson plans for that month. Most had less than 1 year’s experience in preschool teaching.

2.3. Participants

Sixteen students from each of the 5 intervention and 5 control preschools were randomly selected from class lists of 20–

25 children to participate in this study. Consent was obtained from their parents to assess children’s vocabulary and to

interview mothers for demographic information. The other children attended classes as usual but were not tested. Of the 80

children enrolled for each group, 75 from the intervention group and 78 from the control group were present to take the

posttest. Consequently data from 153 children were analyzed. Because all children spoke Bangla at home, the materials and

activities of the preschool and of our intervention were in Bangla. Local words, which the teachers and children shared, were

used freely by teachers to facilitate understanding.

2.4. Measure and testing procedure

The goal was to assess the acquisition of new expressive vocabulary learned through story reading. In the absence of any

list of age-specific words for these Bangla-speaking children, a list was created of words that fit two criteria: they should be

known to grade 1 or 2 children but unknown to preschoolers, and they should be used in the storybooks. A list of difficult

words was first selected from the grades 1 and 2 readers. The expressive vocabulary of a sample of first and second graders

was tested with these words. Words known by more than 50% of them were retained. This new list was then administered to

children of several non-participating preschools; words known to most of them were excluded. The final list of 170 words

constituted the vocabulary test (obtainable from the first author). Using instructions from expressive vocabulary tests, such

as the 4–7-year-old WPPSI, research assistants blind to the child’s group asked, ‘‘What is —?’’ After a partial answer, children

were probed for more with words such as ‘‘Tell me more’’ or ‘‘What else?’’ Answers were later scored 0, 1, or 2 according to

A. Opel et al. / International Journal of Educational Research 48 (2009) 12–20

15

the number of defining features and functions given. Two of the researchers coded and scored the answers, and a third

checked 20% of each group; no changes were required.

A group of 10 female research assistants with university degrees administered the vocabulary test to individual children

and interviewed their mothers. Four assistants had extensive prior experience assessing preschool children using measures

such as the WPPSI vocabulary test. For this study all received a half-day training before the pretest and again before the

posttest on how to interact with the children, how to ask for definitions, and how to record responses. Children were

pretested during the few weeks before the reading intervention and posttested 1-week after its completion, that is 6–7

weeks after the pretest. It was accomplished in one session of 30–40 min because for many words children did not have even

a partial answer. Mothers were asked about their years attending school, household assets (a proxy for socioeconomic

status), and the child’s birthdate.

2.5. Description of Intervention

2.5.1. Books and materials

The intervention started in mid-July 2006 and continued for 4 weeks. Eight fiction storybooks for preschoolers newly

created and published by the Early Childhood Development Resources Center (ECDRC) at the BRAC University Institute of

Educational Development (BUIED) were used because they were unfamiliar to the children (see titles in Appendix A). The

books were selected on the basis of the following criteria: each book contained a sufficient number of new words that were

appropriate for 5-year-olds but unknown to most, story plot was interesting and the illustrations were attractive to

preschoolers and helpful for teachers explaining the story. Books were 11–14 pages in length and had a quarter page of text

with full page illustrations in the background. They were created for Bangladeshi preschoolers and similar to ageappropriate storybooks currently used by these preschools. The stories in the books were modified slightly to include words

from our list of 170 words. Altogether, the 8 books contained all the 170 words on the vocabulary test. Both intervention and

control preschools received and used the same 8 books over the 4-week period. However, only the intervention teachers

were provided with and trained to use the sample open-ended questions to be described; only the intervention schools

received picture cards of the new words (see description below).

Sample ‘‘wh’’ questions for each of the books were prepared to guide the teachers’ verbal interaction when reading the

stories in a dialogic manner. This was considered necessary given the teachers’ lack of extensive training in early childhood

education and their inability in previous programs to ask thought-provoking questions. Some questions asked about the

meaning of new words (e.g., What is a boat? What does a boat do? Has anyone ridden in a boat?), and some about the causes

and consequences of events (e.g., What happened when Kutus fell from the boat? How was he rescued?). We provided about

5–8 sample questions for each book but in practice teachers added their own questions particularly for new words. Teachers

were kept unaware of the words in the test list, so that they would not emphasize only these words in their dialogue.

Because some of the new words inserted in the books were not available in the book illustrations, picture cards were

prepared to illustrate some of these. They were used by the teachers to discuss certain words and were available during play

time for children to handle and discuss with peers.

2.5.2. Dialogic story reading procedure

Both dialogic and regular reading took place with the whole class of 20–25 children. The initial plan was that the teacher

would read each of the books over the course of 3 days: reading the complete story on the first day, and again on the third

day, with discussion on the second day. However, in a pilot run, children refused to listen to the repeated story, saying they

already knew the story and they wanted another. So the story was read in thirds with open-ended questions asked about the

parts just read. This way, one book was covered in 3 days with 30–40 min/day, and two books in a 6-day week.

2.5.3. Teacher training and supervision

Five-day training was provided to the 5 dialogic reading teachers as well as their 5 supervisors. Because the teachers were

paraprofessionals, they were provided with the sample questions and answers, as well as intensive training on how to

conduct the reading, formulate questions, use the illustrations of the book to elaborate the story, use the picture cards, give

real life examples so that children understood better, and engage children in responsive talk. However, as training

progressed, teachers became confident about creating their own questions and not relying on the sample questions-andanswers provided to them. This was also observed during the actual classroom reading.

Training started by watching two videos: one showing a teacher reading a storybook to children in a traditional manner

and another in a dialogic manner. After watching the first video, the teachers identified problems with her reading. After the

second video, teachers noticed the differences in both the reading and the children’s responses. Then teachers watched a live

demonstration of how to read a storybook in a dialogic manner, use the illustrations and the picture cards, formulate

questions and relate an answer to a real life example. Each of the teachers was then asked to read a book in a dialogic manner,

while the other participants played the role of students. Problems were corrected through discussion. This practice

continued for 3 days to allow each teacher to read each of the 8 books individually. Then they were taken to a nearby

preschool to practice with children.

Supervision was also provided to the teachers during the 4-week intervention. Each school was visited almost every day

to ensure that classes were held regularly and instructions followed. In the beginning of the program, most of the teachers

16

A. Opel et al. / International Journal of Educational Research 48 (2009) 12–20

had problems ensuring child participation because this was unfamiliar to the children. However, within a few days the

program unfolded as expected.

2.5.4. Control story reading procedure

Teachers of control schools were given the same 8 books with the same new words. However, they read them in the usual

manner according to their monthly training and instruction. They were requested to spend 40 min a day on story reading,

but their procedure usually took only 20 min and the remaining time was spent on ‘‘morning news’’, another expressive

language activity which preceded or followed story time. The regular story reading procedure consisted of reading each book

once, and asking either yes–no questions or a question that required children to repeat a phrase from the text. The same

procedure was to be followed when the book was read a second and third time, with increasing emphasis on children telling

the story themselves. Morning news was given by individual children. Each day, six were selected to tell the others what had

happened to them that morning; three other children were then to ask questions of each. The control schools were also

visited regularly for observation.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the sample

Among the intervention children, 34.7% were boys and 65.3% girls. Among the control group this proportion was 51.3%

boys and 48.7% girls. As seen in Table 1, the ages of the children did not differ in the two groups. Neither mothers’ education

not family assets in terms of 11 household items differed between groups. Approximately one-third of the mothers in both

groups had not attended school, one-third had attained some primary schooling and one-third some secondary schooling.

Land use and home ownership also did not differ.

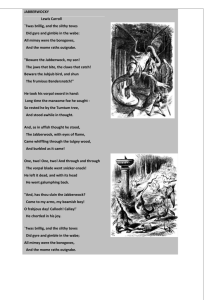

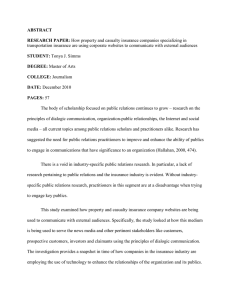

3.2. Vocabulary

The vocabulary test had 170 items that were scored from 0 to 2. The alpha coefficient on pretest scores was .96 and on

posttest scores .99. Consequently each child’s score was the sum of points across all 170 items. Pretest and posttest scores are

presented in Table 1 and Fig. 1. Pretest scores, compared with a t-test, were significantly different, with the dialogic group

ahead. The posttest scores were therefore subjected to an analysis of covariance, covarying the pretest score, the child’s age,

mother’s education and family assets. Only the pretest covariate was significant, as expected. The posttest score yielded a

significant effect for group, F(1, 152) = 220.87, p < .0001, partial h2 = .60. The effect size d = 2.0. It was based on the means

adjusted for covariates, as follows: the control students had an adjusted posttest mean of 80.00 (SError = 4.64) and the

Table 1

Mean (SD) and t-values comparing control and intervention students.

Variable

Control (n = 78)

Child’s age (months)

Mother education (year)

11 Household assets

66.15 (10.8)

4.55 (4.1)

7.13 (2.4)

Intervention (n = 75)

64.73 (8.3)

4.49 (4.0)

7.31 (2.4)

Vocabulary pretest

Vocabulary posttest

75.73 (29.1)

77.12 (37.2)

86.92 (23.6)

183.04 (49.3)

t (151)

.91

.09

.46

2.60

Fig. 1. Vocabulary scores of control and intervention children before and after the reading program.

p

ns

ns

ns

.01

A. Opel et al. / International Journal of Educational Research 48 (2009) 12–20

17

Table 2

Frequency of children providing at least a partial definition to a selection of words at pre- and posttest from the Control and Dialogic Reading groups.

Word

Rope

Colourful

Sleep

Kite

Thank

Tobla (drums)

Giraffe

Difficult

Gift

Ice

Sky

Control (n = 78)

Intervention (n = 75)

Pretest

Posttest

Pretest

Posttest

63

60

64

42

28

19

5

26

30

35

41

67

60

67

42

42

30

8

27

31

35

43

65

63

68

53

36

21

7

21

33

31

46

69

69

73

67

64

59

40

57

60

61

68

intervention students an adjusted mean of 180.12 (SError = 4.74). The improvement as a result of the dialogic reading

intervention was large.

Table 2 provides some examples of the words on the test list and the number of children who received a score of 1 or 2 on

pretest and posttest. Some words were well-defined at pretest, such as rope, colourful, sleep and kite, and showed a slight

increase in both groups. Other words showed improvement in both groups but more in the dialogic group, such as thank and

tobla (drums). The concepts behind these words were probably familiar to most children and perhaps they were wellclarified in the stories and illustrations. Most other words, like giraffe, difficult, gift, ice, and sky were considerably better

defined on the posttest by dialogic reading children.

Researchers conducted observations in both Dialogic and Regular preschools, though it was more systematic in the

former. Observations were recorded in written form. At the dialogic schools, teachers and children became accustomed to

the participatory procedure within a week. At first teachers relied on the questions given for the book and had a difficult time

getting answers from the children. However, in the second week they were generating some of their own questions and

responding to children’s answers with a follow-up question or by asking other children to offer their ideas. Our observations

were that teachers increased substantially the number of questions over time, but that responsive feedback increased less

dramatically. Children also were slow to answer the questions at first because they had been used to only repeating the

teacher’s phrases. Children in both programs paid full attention; in fact story time was very popular and children eagerly

positioned themselves to have a good view of the book illustrations. However, those in the dialogic reading program were

more active in talking and listening to the teacher and to each other. They answered individually and their answers were

therefore unique. Most eventually offered answers and elaborated extensively on their answers; however even the few who

remained shy were alert. Teachers encouraged them to elaborate with experiences from their own life (e.g., had they ever

flown a kite?), and they did. Several children each day were observed to play with the picture cards illustrating some new

words from the stories. They were seen to talk with peers about the pictures.

Control teachers, in contrast, asked questions in a predictable way, usually requiring that children repeat the last phrase

or simply answer ‘‘Yes’’. Typically all the children would reply loudly in unison. Their comprehension was thereby not tested.

Children did not frequently ask the teacher for clarification so the teacher showed little responsiveness. The teachers’ goals

were largely to help children understand and then memorize the story. To this end, they often stated the story in simpler

words, and on second and third readings encouraged children to tell the story from the pictures before she read the words.

The ‘‘morning news’’ activity which preceded or followed was more specifically aimed at developing expressive language.

Each day, six children recounted their recent experiences to the class and three others were to ask questions about these

experiences. The ‘‘news stories’’ varied considerably in length from one to several sentences. Children’s questions were

largely rhetorical in the sense that everyone already knew the answer (e.g., If the story teller said, ‘‘I saw three men this

morning,’’ a questioner might ask, ‘‘How many men did you see?’’). Teachers did not model more interesting questions.

4. Discussion and implications

The hypothesis was that dialogic reading in this brief intervention would result in increases in children’s expressive

vocabulary. This was strongly confirmed with a large effect size. Children in the intervention group rose from a mean of 26%

to 54%, whereas control children did not improve. Scores were intentionally low at the pretest in order to assess the

acquisition of new vocabulary. Unlike prior research, we used a measure of expressive vocabulary that required a definition,

as this is a common demand of vocabulary tests for this age group.

Previous studies have found that children who participate in dialogic reading activities show improvements in

vocabulary (e.g., Hargrave & Senechal, 2000; Lonigan & Whitehurst, 1998; Whitehurst et al., 1994). Improvements are

greater with children whose vocabularies are below the norm for their age, and when parents supplemented preschool

reading with dialogic home reading (e.g., Chow & McBride-Chang, 2003; Heubner, 2000). The current study supports

previous research in showing the short-term benefits of dialogic reading on vocabulary acquisition. It extends prior research

18

A. Opel et al. / International Journal of Educational Research 48 (2009) 12–20

by demonstrating that the dialogic reading procedure is effective at raising expressive vocabulary, in a low-literacy and lowresource country, and when implemented by a paraprofessional teacher with a group of 20–25 preschoolers. With groups

this size, not all children were overtly engaged in the dialogue at any one time. Presumably the children were mentally

engaged enough to benefit. The fact that many children wanted to express their ideas meant that the reading period lasted

longer than is usual with paired or small group dialogic reading (30 min vs 10 min). Nonetheless, extra demands are placed

on the reading adult to keep children actively involved even when they are not talking. Dialogic reading children also had

access to picture cards of the new vocabulary words to manipulate during free play. Another whole-class dialogic reading

program with early Head Start children found that repeated exposure to vocabulary during after-reading activities

contributed to vocabulary gains (Wasik, Bond, & Hindman, 2006).

The regular group seemed to have acquired very little new expressive vocabulary. Although they spent less time on the

story, they did spend the remaining time in spontaneous conversation intended to improve expressive language. The activity

might have encouraged confidence in speaking aloud but did not introduce new vocabulary. Questions posed by the children

did not encourage the story-teller to elaborate or introduce new words. Likewise, the style of story reading did not clarify the

meaning of new words for children, and they were unable to derive meaning from the story or illustrations. Rather than

explain new words to children, the regular teachers often avoided repeating the new word in preference for using a simpler

phrase that they felt children would understand. Furthermore, their questions required passive repetition of book phrases,

and so gave children the impression that accurate repetition rather than comprehension mattered. Teachers may still hold

the belief that stories are meant to be enjoyed and memorized—important values when the society was largely illiterate.

However, now that over 80% of children are sent to school, academic achievement and literacy have become priorities for

most parents (UNICEF, 2006). Dialogic reading is a highly effective alternative that meets the current need for literacy.

The intervention was intentionally brief in order to examine the efficacy of this new technique in Bangladeshi preschools.

One reason for the short duration was that only 8 books met the criteria of being created in Bangladesh, yet unfamiliar to the

children, and with sufficient new vocabulary. The second reason was the skepticism that such a program could be

implemented by teachers and effective with children. Other published studies have used 4–6 weeks (e.g., Hargrave &

Senechal, 2000; Heubner, 2000; Valdez-Menchaca & Whitehurst, 1992) or 8–12 weeks (Chow & McBride-Chang, 2003;

Wasik et al., 2006). Short programs tend to be effective with younger children of 2–3 years (e.g., Valdez-Menchaca &

Whitehurst, 1992) perhaps because their vocabularies are increasing rapidly at this age, and with older children of 3–5 years

if the book vocabulary was assessed (e.g., Hargrave & Senechal, 2000). Likewise, we found large gains with a brief

intervention for 5–6-year-olds when evaluated on the book vocabulary.

Skepticism centered around whether teachers could overcome the large gap between their current reading style and the

demands of dialogic reading. Given the preschool teachers’ paraprofessional status, with most training being short and inservice, they were previously unable to adopt a more responsive and inferential question-and-answer repertoire (Moore

et al., 2008). When asked about the benefits of story reading, teachers mentioned enjoyment and memorization but not

vocabulary. The training for dialogic reading was adapted to these conditions by providing examples of questions on the back

of books, a training video and coached practice. A similar training procedure was found to be most effective with high-school

educated mothers of young American children (Heubner & Meltzoff, 2005). However, to avoid a repetitive and boring

instructional style (Kotaman, 2007), teachers had to create some of their own questions and expansions to follow-up on

children’s responses.

The limitations of the study lie mainly with the lack of a measure of children’s wider vocabulary, and no systematic

recording of teachers’ dialogic reading style. We would not expect general vocabulary to improve with a short focused

intervention, given the children’s low standardized vocabularies (e.g., Hargrave & Senechal, 2000), though it potentially

could with a longer intervention (Wasik et al., 2006). Furthermore, we did not systematically record the number of openended questions and expansions offered by the teachers during a session. This would have allowed us to monitor change in

the teachers’ dialogic features over time, and compare the vocabularies of children whose teachers used more or less dialogic

features. The major strength lies with its random assignment of preschools to intervention and control; although individual

children were not randomly assigned they were similar in the two groups.

The major contribution of the study is its demonstration of a very large effect of dialogic reading on children’s expressive

vocabulary, using definitions as the outcome. This measure capitalizes on an important feature of dialogic reading, namely

encouraging children to use words in a clear descriptive manner. The children participated in large groups, and so were

exposed to peer models as well as an adult. The context was also different from other studies in that the children lacked

books, radio and television at home, and so relied on the preschool for literacy experience.

If we speculate on the reasons for such a large effect size, several explanations come to mind. One is that dialogic-reading

children received practice in providing definitions and more broadly in answering open-ended questions. The picture cards

gave them a second opportunity to view some of the new words in a peer-play context. Control children were also providing

proper definitions at the pretest, but they did not have training in expressing the meaning of words, and perhaps the need to

focus on distinctive features and functions. The dialogic children were also more cognitively active when listening to words

and events; connecting the unfamiliar words to something familiar would provide a set of associations to facilitate recall and

meaning. Finally, children may start with low vocabularies because they lack responsive and sophisticated dialogue with an

adult. Children in the regular program were not sufficiently challenged with new words because their teachers minimized

difficult words and instead focused on enjoyment and memorization. Given this low-literacy background, stimulating and

responsive talk about stories and pictures had a large effect.

A. Opel et al. / International Journal of Educational Research 48 (2009) 12–20

19

It is important to translate research into practice. This research demonstrated that the ongoing programs could be

improved significantly with benefits to the children if minimal but systematic efforts were put into materials, training, and

supervision. In Bangladesh, the importance of preschool programs has been acknowledged by the government and by nongovernment organizations. As a result, more resources have been channeled and program coverage has been increasing.

However, there is still a need to improve the quality of the programs. The major hurdles are materials which tend to be

undemanding, and teachers who have little experience with responsive talk. However, when provided with vocabularyladen stories, ready-made provocative questions, and intensive training, the teachers were successful in implementing

dialogic reading.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by various individuals and organizations. Save the Children

U.S. and Village Education Resource Centre permitted the dialogic reading program to be conducted and evaluated in their

preschools. Funds were provided by the BRAC University Institute of Educational Development. The Institute’s advisory

committee consisting of Dr. Manzoor Ahmed, Professor Nazmul Haque, Dr. Fahmida Tofail and Dr. Cassie Landers reviewed

the protocol for scientific and ethical approval. Administrative support was provided by Dr. Sudhir Sarker and Mahmuda

Akhter. Data were collected by Shashoti Dwean, Nasrin Akhter, Tashmia Sultana, Khodeja Akhter, Afroja Sultana, Washima

Parveen, Farah Deeba, Shamsunnahar Chonda and Nusrat Sharmin. Dilshana Parul entered the data and Faizun Nessa

supervised. Kamal Uddin sketched all the pictures. Finally, we are grateful to the preschool teachers and students along with

their mothers for participating in the research.

Appendix A. List of the books used in the research, produced by ECDRC, BU-IED

Akhter, M. (2006), Kossoper Golpo.

Chakma, S. (2006), Ajob Juto.

Faisal, M.K. (2006), Nouka Vromon.

Hossain, I. (2006), Nijhum Bone Ganer Ashor.

Islam, S. (2006), Doitter Deshe Onima.

Khanam, M. (2006), Shopna O Mithur Sheyal Dekha.

Rashed, M. (2006), Ripa O Picchi Vut.

Shahabuddin, A.B.M. (2006), Khorgosher Jonmodin.

References

Aboud, F. E. (2006). Evaluation of an early childhood preschool program in rural Bangladesh. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21, 46–60.

Aboud, F. E. (2007). Evaluation of an early childhood parenting program in Bangladesh. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 25, 3–13.

Blake, J., Macdonald, S., Bayrami, L., Agosta, V., & Milian, A. (2006). Book reading styles in dual-parent and single-mother families. British Journal of Educational

Psychology, 76, 501–515.

Britto, P. R., & Kohen, D. (2005). International perspectives on school readiness assessment. New York: Unicef.

Chow, B.W.-Y., & McBride-Chang, C. (2003). Promoting language and literacy development through parent–child reading in Hong Kong preschoolers. Early

Education and Development, 14, 233–248.

Early Childhood Development Resources Center (ECDRC). (2006). Extent of early childhood development programs in Bangladesh: An activities and resources map.

Dhaka, Bangladesh: BRAC University Institute of Educational Development (BUIED).

Evans, G. W. (2004). The environment of childhood poverty. American Psychologist, 59, 77–92.

Hargrave, A. C., & Senechal, M. (2000). A book reading intervention with preschool children who have limited vocabularies: The benefits of regular reading and

dialogic reading. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15, 75–90.

Heubner, C. E. (2000). Promoting toddlers’ language development through community-based intervention. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 21, 513–

535.

Heubner, C. E., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2005). Intervention to change parent–child reading style: A comparison of instructional methods. Applied Developmental

Psychology, 26, 296–313.

Hoff, E. (2003). The specificity of environmental influence: Socioeconomic status affects early vocabulary development via maternal speech. Child Development, 74,

1368–1378.

Hoff, E. (2006). Language experience and language milestones during early childhood. In K. McCartney & D. Phillips (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of early childhood

development. Oxford: Blackwell.

Kotaman, H. (2007). Turkish parents’ dialogical storybook reading experiences: A phenomenological study. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 34, 200–206.

Lonigan, C. J., & Whitehurst, G. J. (1998). Relative efficacy of parent and teacher involvement in a shared-reading intervention for preschool children from lowincome backgrounds. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 13, 263–290.

Moore, A. C., Akhter, S., & Aboud, F. E. (2008). Evaluating an improved quality preschool program in rural Bangladesh. International Journal of Educational

Development, 28, 128–131.

Raikes, H., Pan, B. A., Luze, G., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Brooks-Gunn, J., Constantine, J., et al. (2006). Mother–child bookreading in low-income families: Correlates

and outcomes during the first three years of life. Child Development, 77, 924–953.

San Francisco, A. R., Arias, M., Villers, R., & Snow, C. (2006). Evaluating the impact of different early literacy interventions on low-income Costa Rican

kindergarteners. International Journal of Educational Research, 45, 188–201.

Senechal, M. (2006). Testing the home literacy model: Parent involvement in kindergarten is differentially related to Grade 4 reading comprehension, fluency,

spelling, and reading for pleasure. Scientific Studies of Reading, 10, 59–87.

Snow, C. E. (2006). What counts as literacy in early childhood. In K. McCartney & D. Phillips (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of early childhood development. Oxford:

Blackwell.

20

A. Opel et al. / International Journal of Educational Research 48 (2009) 12–20

Storch, S. A., & Whitehurst, G. J. (2002). Oral language and code-related precursors to reading: Evidence from a longitudinal structural model. Development

Psychology, 38, 934–947.

UNICEF. (2006). State of the world’s children. New York, NY: UNICEF.

Valdez-Menchaca, M. C., & Whitehurst, G. J. (1992). Accelerating language development through picture book reading: A systematic extension to Mexican day

care. Developmental Psychology, 28, 1106–1114.

Wasik, B. A., Bond, M. A., & Hindman, A. (2006). The effects of a language and literacy intervention on Head Start children and teachers. Journal of Educational

Psychology, 98, 63–74.

Whitehurst, G. J., Arnold, D. S., Epstein, J. N., Angell, A. L., Smith, M., & Fischel, J. E. (1994). A picture book reading intervention in day care and home for children

from low-income families. Developmental Psychology, 30, 679–689.