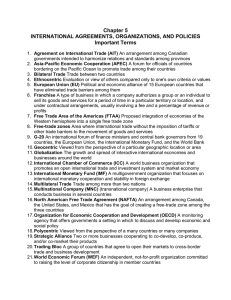

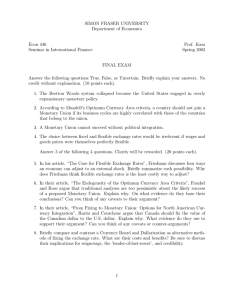

International Spillovers of Monetary Policy

advertisement