Czech Republic

advertisement

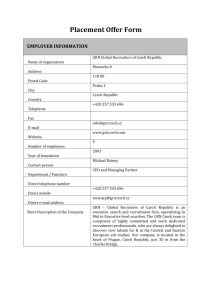

New intermediary services and the transformation of urban water supply and wastewater disposal systems in Europe Working Paper Current Status of Water Sector Restructuring in the Czech Republic Matthias Naumann Institute for Regional Development and Structural Planning (IRS) Flakenstr. 28-31 D-15337 Erkner E-Mail: Naumann@irs-net.de Web: http://www.irs-net.de September 2003 “Intermediaries” is an international research project funded by the European Commission under the Framework 5 Key Action “Sustainable Management and Quality of Water (contract EVK1CT-2002-00115) Duration: 11/2002-10/2005 i Copyright: This paper must not be published elsewhere (e.g. mailing lists, bulletin boards etc.) without the author‘s explicit permission and must not be used for commercial purposes. If you cite, copy or quote this paper you must include this copyright note, regarding the conventions of academic citation: Matthias Naumann: Current Status of Water Sector Restructuring in Czech Republic, Working Paper published by the EU-project Intermediaries (website: www.irs-net.de/intermediaries/WP1_CzechRepublic.pdf) i Contents Pages The Intermediaries Project i Executive summary iii 1. Introduction 1 2. Existing status of liberalisation 1 2.1 Country specific approach to privatisation/liberalisation 1 2.1 Specific status of water liberalisation 2 2.3 Legal framework for water market restructuring 4 Figure 1: Ownership of water operators in the Czech Republic 4 2.4 Actors in the privatisation process 5 2.5 Examples for private investments in the Czech water sector 6 3 Social and technological structure of the water sector 9 3.1 Organisational structure 9 3.2 Technological structure 11 4. Restructuring of water market 12 4.1 Demand 12 4.2 Water supply and quality 12 Figure 2: Development of water supply and wastewater collection coverage 1989-2001 13 4.3 Prices Figure 3: Development of water prices 1993-2002 4.4 Employment 15 15 Figure 4: Employment in the Czech water sector 16 4.5 Investment 16 5. Debates specific to liberalisation of water sector 17 6. Emerging and future trajectories of water sector liberalisations 19 7. Key sources and other relevant information 21 7.1 Literature 21 i 7.2 Web sources 24 7.3 Expert interviews 24 i The Intermediaries Project: New intermediary services and the transformation of urban water supply and wastewater disposal systems in Europe This report forms part of a wider EU Framework 5 project “New intermediary services and the transformation of urban water supply and wastewater disposal systems in Europe” is an EU Framework 5 project under the Programme Key Action “Sustainable Management and Quality of Water” (contract no. EVK1-CT-200200115). The project fills a knowledge gap on the current restructuring of the water sector across Europe by mapping the development of intermediary activities and organisations and assessing whether, in what ways and in what institutional and organisational contexts these services can accelerate the application of resourcesaving technologies and social practices. Reviewing the Accession States The first work package of the project is a review of current status of water market liberalisation across Europe, providing an institutional backdrop for context-sensitive analysis of intermediary activities. More specifically our review focuses on the current status of the accession states. The comparative report and working papers for each accession state are available on the website. Methodological Challenges There are particular methodological challenges involved in reviewing the processes of restructuring across the accession states. There are relatively few academic or policy accounts of the processes of water sector transition in the accession states. There are also few secondary sources available through web-based and/or library searches. Consequently: • There are few secondary sources documenting changes we can be used to clarify the validity of the findings • Rapid change in some of the accession states means it is difficult to provide up to data and reliable information ii • Large variability in the application of policies within countries means that careful consideration between intention and actuality must be taken Given these source limitations each country report has also been reviewed by a country representative with expertise in the water sector and subsequently revised in response to their feedback. Working Definitions In order to allow comparisons of the Accession states the project has developed simple working definitions: • Liberalisation: Reforming legal frameworks to permit and regulate competition in the water market. • Commercialisation: Adoption of business management practices characteristic of the private sector in order to improve the efficiency, effectiveness and/or market position of a water/sewage utility. • Privatisation: The transfer of ownership, responsibility or service provision from the public to the private sector. iii 1. Executive summary Czech Republic Liberalisation The current legislative framework has liberalised the water sector primarily by permitting the private sector involvement of water companies. The liberalisation of the water sector is founded on the Large Privatisation Act (1991), which foresees the transfer of rights and the sale of shares to private companies; the Amendment to Small Businesses Act (1996), by which rights over water supply and sewerage systems became licensable and were transferred to private companies; and the “Act on Water Supply Systems and Sewage and Drainage Systems” that defines the standards for concessions of operators for drinking water supply and wastewater disposal. The private sector involvement of the water sector was implemented during the second stage of coupon privatisation (1993-1995). Commercialisation Drinking water supply and waste water sewerage is managed in most cases by private companies. Prices are fixed by the municipalities according to the restrictions of the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Environment. Nevertheless there have been dramatic increases in water prices. Private sector involvement The water sector is almost fully privatised, as the ownership of water/ wastewater companies has been transferred to private investors. Private companies act as operators while the ownership of the water infrastructure remains in municipal hands. Water management companies like the river basin boards are in public ownership. Country specific issues The fragmentation of the water sector, which poses an obstacle to efficient water investment and the dominance of large multinational companies (Vivendi, Ondeo, Anglian Water). Future Trajectories All experts see a trend towards more private involvement. The Czech trade union CMKOS expects that in the future two multinationals (Vivendi and Ondeo) will control up to 90% of the Czech water market. There is also still need for a regulatory body for the water sector and a fixed definition of ‘water’ and water rights in the Czech constitution. Finally, to meet the challenges of limited public finances and the need for investments considerable effort is needed to educate staff in water management issues. iiii 1. Introduction This report provides an overview of the status of liberalisation and privatisation in the Czech water market. The report has been compiled with web-based material, secondary literature and five expert interviews held in April 2003 in Prague. The structure of the report is as follows: chapter 3 gives a general overview of the existing status of liberalisation, the main actors and frameworks, chapter 4 introduces the organisational and technological structure of the water sector, while chapter 5 explains the process of restructuring taking place since privatisation and liberalisation. Chapter 6 summarizes the debates on water privatisation and, finally, chapter 7 discusses possible future trajectories of the Czech water market. 2. Existing status of liberalisation 2.1 Country specific approach to privatisation/liberalisation The Czech Republic has pursued the privatisation and liberalisation process at high speed. It was the first country with a workable system of mass privatisation. The legal framework for liberalisation and privatisation was started in 1990/91. The privatisation process in the Czech Republic has to be distinguished between small-scale and large-scale privatisation. Small-scale privatisation means the sale and lease of shops, workshops, hotels and similar properties by public auction to individuals or private businesses. Small-scale privatisation ended in 1993. The second step started in 1994. Large-scale privatisation involves the transfer of state-owned properties to private parties (M LADEK 2001: 124f.). The specific Czech mode of privatisation was via coupon privatisation. Every citizen had the opportunity to buy for 1000 CZK 1000 investment points. These investment points could be used to gain stocks of former state companies (PLATTNER 1996: 140).1 1 This privatisation process is widely discussed: “For governmental liberal economists evaluating privatisation in terms of speed and scale, the privatisation process was a decisive success. However, in light of institutional economics, the results of this process appear much more dubious. In view of the constant bridging and revisions of the original privatisation plans, it was not surprising that doubts about the fair nature of the privatisation process emerged” (Tomasek, 2001: 34). 1i In 2001 about 80 % of economic activity was in private hands (EBRD 2002: 4). There is a large degree of price liberalisation and an open foreign trade regime allows no major constraints to foreign investment. From the start of privatisation to 31.12.2002 there has been a sale of a total number of 14,685 units (http://www.fnm.cz). There are two types of ownership transformation: 1) conversion of state enterprises to jointstock companies and 2) the transfer from state-owned joint-stock companies to private joint-stock companies (http://www.fnm.cz). An important internal driver in the process of privatisation is the rapid worsening of fiscal balances and the need to raise sufficient funds from privatisation proceeds to limit an increase in the state debt (EBRD 2002: 12). 2.2. Specific status of water liberalisation There is no differentiation between water supply and wastewater disposal in the privatisation process. “Water sector” includes always both: drinking water supply and the treatment and disposal of wastewater. In the early days, public services such as water sector were excluded from privatisation for reasons of „infrastructural security“ (MAAßEN/SAUER/NISSEN 2002). The first step in the privatisation of water companies was for the ownership of the assets and operation licences of water companies to be transferred to the municipalities. In a second step the Czech Republic privatised the water sector under the Large Privatisation Act in 1992 (Law 92/1991), which provides for the transfer of assets and the sale of shares to the private sector (M INISTRY OF THE ENVIRONMENT 2003). Reasons given for privatisation include the argument that private companies are seen as better operators for providing water services and there was a need for external funding for investments. Political pressure from the EU to force infrastructure investment and from the Czech government to reduce to zero its nonrecoverable investment in infrastructure caused the smaller municipalities to seek external funding. The Czech Republic is obliged to implement EU directives concerning drinking water and wastewater, which raises new challenges for the infrastructure investments. Now the privatisation process is almost completed. Only a small proportion remains in public hands. There are no restrictions on foreign companies buying shares in Czech water companies and there is no legal distinction between foreign and Czech companies. 2i The first foreign investor who bought shares in a Czech water company was Ondeo in 1993, buying 10 % of the water company in Brno. In 1991, the Czechoslovakian Government invited the British water utility Anglian Water to join a project for the upgrading of water and sewage services in South Bohemia. Anglian Water now owns 97% of Vodovody a Kanalizace Jizny Cechy (VAKJC), a joint venture company that was created to serve a population of about 400,000. The first Czech water management company with a majority share owned by foreign investors was Vodovody a kanalizace Jizni Cechy (VaK JC) in 1999. Today most of the Czech water market is in the ownership of multinational companies (see Figure 1). The market shares for 2002 were as follows: 40 % served by Vivendi Water, 18 % by Ondeo, 13 % by Anglian Water, 1 % by Gelsenwasser and the rest by municipal companies. According to a Czech trade union in 2002 69.7 % of Czechs were supplied with drinking water by Vivendi, Ondeo and Anglian Water, who provided 74.9 % of the water sold using 80.7 % of the water supply pipes. In the wastewater sector 79.8 % of all inhabitants, 55.4 % of the pipes and 76.3 % of the wastewater is managed by the three big multinationals (C MKOS 2003). The extent of water privatisation in the Czech Republic is now higher than the European average and even higher than in Great Britain or France (Interview 5). 3i Figure 1: Ownership of water operators in the Czech Republic | Ownership of water operators in the Czech Republic ANGLIAN WATER ONDEO SERVICES Gelsenwasser VIVENDI WATER Tábor DC MO TP CV UL KV MB PH AB Beroun RO TC NA HK NB KO Bruntal UO K H Pl BN PJ JE RK PA PZ PB TU JC ME RA PS SM Ceský Krumlov KL CH Negotiations with private companies not yet completed JN CL LT LN SO LB Prachatice SU CR OP OS SY HB Olomouc KA NJ FM DO PI KT TA ZR PE BK PV Prerov JI ST JH TR BO BM Vsetin KM VY ZL PT Domažlice CB ZN CK HO UH BV Duben 2002 Source: VIVENDI 2002 2.3. Legal framework for water market restructuring It is claimed that “the main privatisation and transformation steps in water management have been already realised” (INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON IRRIGATION AND DRAINAGE/E UROPEAN REGIONAL WORKING GROUP 1998: 172). The water sector is nearly full privatised, while privatisation in the energy industry has just started. In legislative terms, privatisation did not take the form of a special act. An initial governmental decision was issued in 1992, which established following conditions for the approval of privatisation projects: 1) The owners of the infrastructure may be local authorities, groups of communities, and/or joint-stock companies in which the local authorities are major shareholders (with a holding of 80-100 % of the shares) 4i 2) The so-called operational property of the formal provincial water supply and sewage companies - e.g. buildings, transport and construction machinery, workshops, operational centres - could be privatised using standard methods of privatisation 3) Each privatisation project should also take into account the viewpoints of the involved municipalities with respect to the process of privatisation (ibid.: 32). These regulations opened the way for the second phase of privatisation. There exist in practice many different pathways of privatisation. The most common mode is for the municipalities to remain the owners of the assets. This entails the separation of the infrastructure and the operational property. A local authority or a group of local authorities owns the water management infrastructure, while the operational property is transferred to joint stock companies or sold to the private sector. The act on water supply systems and sewage and draining systems defines operation such that “it does not include administration of water supply and sewage systems property nor its development” (§ 2, ch. 3). But there are also exceptions: in the region around Ostrava in Northern Moravia, Anglian Water is also the owner of the assets (http://www.anglianwater.co.uk/inter/czech.asp). Another method is the model of leasing contracts. A private sector company is entrusted with managing, maintaining and operating the existing water infrastructure. The private company is not committed to invest in the existing infrastructure (PWC 2002). The privatisation process was accompanied by legal regulations such as the Water Management Act in 1995 that was issued as an accompanying publication to the Directory Plan in Water Management (DPWM, Czech: SVP) and the Act on Water and the Act on Drinking Water Supply and Sewage Systems in 1992. In 2002 a new law was passed which defines the restrictions for operation licenses. The license to run a business “operating water supply and sewage systems for public use” is assigned by the Ministry of Agriculture. 2.4. Actors of the privatisation process A key actor of the privatisation process is the National Property Fund of the Czech Republic (FNM). It is charged with the temporary task of exercising the ownership 5i rights in companies in which the state holds an ownership stake intended for subsequent privatisation (http://www.fnm.cz). The water companies were privatised through the agency of FNM. After the transfer of the water infrastructure to the municipalities these became the main actors of privatisation. They decide – according to the restrictions of the Ministry of Agriculture - how to privatise their water companies. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the World Bank group have actively supported the privatisation process. One example is the Brno-Modrice wastewater treatment plant where the EBRD supports the Brnenske Vodarny a Kanalizace (BVK), a partly privatised municipal utility company (51 % City of Brno, 39 % Suez Lyonnaise des Eaux, 10 % private investors) with a loan around € 42,5 million. This investment enabled the enlargement and upgrading of the plant. It was the first loan of the bank for the Czech water supply sector and the first loan for a water and sewage company without a full guarantee from the municipality (http://www.ebrd.com). As part of the project, the EBRD assisted the city in amending an existing long-term concession contract between the city and a joint stock company minority-owned by an international operator (EBRD 2002: 7). Small projects in cooperation with the EBRD were also initiated in Ostrava and Plzen (ibid.: 37). The Czech state is also involved as a motor behind the creation of a private water sector. As Hall comments, „public authorities are also expected to provide financial guarantees, which minimise the risk transferred to the private sector. These include guarantees of loans; development banks especially may require a government guarantee before any money can be lent to a privatised and guarantees of profitability. Many water concession contracts include clauses under which public authorities guarantee the profitability of the operator for the duration of the contract – e.g. Plzen “ (HALL 2002: 3). Nevertheless there remain various risks for private investors e.g. high operating costs of the water supply and sewage systems. 2.5 Examples for private investments in the Czech water sector The following chapter illustrates the above with examples of privatisation projects in the Czech water sector. 6i a) Prague Vivendi Water, a subsidiary of Vivendi Environment (VE), bought together with the AWG consortium a 66 % stake in the Prague water utility (Prazské vodovody a kanalizace-PVK) in 2000 for €174 million. The remaining 33 % will be transferred to the City of Prague free of charge. PVK was a legal successor to the state companies Prague Waterworks and Prague Sewage and Watercourses. Its main activity is drinking water supply, operation of the sewage system and wastewater treatment. VE/AWG will provide all water and wastewater services for 1.2 million people living in Prague and its suburbs until 2013. The contract is worth an average revenue of €110 million a year for 13 years. The decision for Vivendi, active in the Czech water market since 1995/6, to become engaged in Prague was influenced by the price, its strategy outlined in the business plan, technical proposals and productivity gains. VE/AWG proposed a rapid reduction in leakage from the Prague network, improved treatment of the city’s wastewater, a staff training programme and the introduction of a customer services centre. The privatisation of PVK is of extraordinary importance for the Czech water market. PVK was the last major privatisation of water companies in the Czech Republic. Vivendi itself attributes strategic importance to the Prague concession. One contributory factor may be the decision of the EBRD to grant a 15-year €50m loan to the City of Prague to finance leakage reduction and improvements to the profitability of wastewater treatment plants in June 1999. The excessively high bid (three times higher than experts estimated) may result in substantial price increases. Vivendi also plans restructuring which will result in a reduction of the number of facilities from seven to three and a cut in the workforce by 200 employees (LOBINA 2001: 5). Including Prague, Vivendi serves 3.4 million people in the Czech Republic and is the market leader in the country. The company leads the Czech municipal outsourcing market. Vivendi Water had estimated revenues in 2001 of €225 million in the Czech Republic and a work force of around 6,000 people (V IVENDI 2001). b) Other regions The Czech Republic’s second largest drinking water producer and distributor Severomoravske vodovody a kanalizace (SmVaK) in North Moravia was bought by 7i Anglian Water and Suez (Ondeo) in April/May 1999 (C ZECH NEWS AGENCY 2000a). SmVAK is the third largest water services company in the Czech Republic and is unique in that it is the only one to own the infrastructure assets (http://www.anglianwater.co.uk/inter/czech.asp). The British company Anglian Water serves 1.3 million customers and has about 2500 employees in the Czech Republic. They used to be the third major international player in the Czech water market. There exist plans, owing to economic difficulties, for Anglian Water to sell all of its shares abroad. In June 2001 an 82 % stake in the Sumperk water company was bought by Suez. Suez serves about 2.1 million people in the country. It manages water and wastewater services for the cities of Brno, the Ostrava region, Karlovy Vary and Southern Moravia. In 2000 it had sales of €6m and employed 200 workers (LOBINA 2001: 6). In June 2001, Suez made a €60m contract over 25 years to build a water treatment in Brno, where it already holds a 31 % stake in the local water supplier Brno VaK. According to the CEO of Lyonnaise des Eaux: “The Czech Republic’s water market is important for business development in Central and Eastern Europe” (SUEZ LYONAISSE DES EAUX GROUP 1999). Vivendi started its activities in the Czech Republic when it bought shares in the water company in Plzen. Vivendi bought stakes in the ScVK in North Bohemia from Hyder in 1998. ScVK is one of the most rapidly expanding private companies in the Czech Republic. The British company Hyder decided to sell its stake because the profit rates were only about 6 %, which is comparable with other European companies, but low compared with profit rates in Great Britain. Another reason for Hyder to sell their stake was that public officials who held a controlling stock in ScVK tried to gain influence to control the prices. ScVK is managed in partnership with the North Bohemian water authority SVS. In August 2001 Vivendi Water won a contract for the collection and treatment of wastewater at the Spolchemie chemical production site in Usti nad Labem. The public SVS will finance this new wastewater treatment plant with €1.5 million. Formerly together with SAUR, Vivendi Water was selected to operate the water company in Olomouc under a 20-year contract starting in April 2000 (V IVENDI 2000). Public officials ensured that the company’s board must approve any changes in water charges and that the contract limited any price rises above the inflation rate (CZECH NEWS AGENCY 2000b). 8i 3. Social and technological structure of the water sector 3.1 Organisational structure Prior to 1990 the public water supply and sewage systems were operated by 9 large state companies, which managed 93 % of the total length of the water supply networks and accounted for 99 % of total drinking water production. The water companies were state companies and the planning process was coordinated by the Ministry of Forestry and Water. After 1990 the central management of the water supply companies and sewage companies was transferred back to local authority responsibility, as it was before 1948. This was based on the Act of Municipalities in 1992. The transformation followed the basic principle of transferring responsibility from the state to municipalities. It reflected a general process of decentralisation of state administration. The highest authority for water management still remains the Ministry of Agriculture. Supervisory authority over water issues is shared between the Ministry of Environment, which is responsible for surface water protection and protection against flooding, and the Ministry of Agriculture, responsible for water management and the water market. The spatial organisation of water supply and wastewater disposal services has changed completely. Before 1990 water distribution was organised according to the administrative structure of the CSSR. After the “velvet revolution” the former organisational distribution system was abolished. Unlike the gas or energy sector there appeared many new forms of various dimensions. The former 9 companies split even before privatisation into 53 companies. The organisational structure of water companies also differs greatly. There exist very small companies and others that serve whole regions. Some municipalities decided to pursue their own paths, while others decided to cooperate. This development was prompted by the fact that there was in some cases insufficient information on the status and objectives of the sector (OECD/DANCEE 2003: 78). The market is organised 9i according to territorial monopolies – a fact that is criticized by liberal economists (Interview 3). After 1990 companies split into different parts and new companies were founded like the 1.JSVS in Southern Bohemia. The process of water market restructuring changed such that public ownership was increasingly replaced by the involvement of private companies. The number of water companies today is disputed in the literature, varying between 74 (CMKOS), more than 100 (OECD/DANCEE) and 130 (SOVAK/Liberalni Institute). Water companies consist of so many facilities that there is a clear need for optimisation processes over the coming years. Joint stock companies often operate as a monopoly in the region they serve. There are three types of ownership of water companies: 1) Municipal companies (infrastructure and operation is in the hands of municipalities), representing only 23 companies or 3 % of water market 2) Limited companies working as operators on the basis of contracts with the municipalities, involving contracts with operators or public shareholders companies 3) Shareholder companies, consisting of two types: 1) shareholder companies which have contracts to act as operators and rent the infrastructure; 2) mixed shareholder companies which own the infrastructure and operate the services. During the 1990s there were attempts to privatise the River Basin Boards as jointstock-companies. River Basin Boards are responsible for the administration and maintenance of significant watercourses, the operation and maintenance of water structures, flood protection and accidental water pollution clear-up, the management of surface water systems including water quality protection, water balance assessments and master plans. River Basin Boards supply drinking water and sell it or the rights of extraction to water companies. The main river basins are divided into 5 river basin districts: Vitava river basin, Ohre river basin, Labe river basin, Odra river basin and Morava river basin. The administrators of these river basin districts – the River Basin Boards – are state enterprises. 80 % of the large water reservoirs in the Czech Republic are managed by the River Basin Boards. It was originally planned to outsource the profitable business of water supply and dams to private companies. The plans to privatise these companies were stopped, however, after the election of the 10i new social democratic government. A political decision has been made to keep the River Basin Boards in state ownership because they serve national interests. 3.2. Technological structure The technological status of the water sector has a major determining influence on the economic success of water companies. The technological situation of the Czech water sector has been rated as follows: “In the Czech Republic, levels of service, technical condition and performance were not the main drivers for beginning sectoral changes (…). The main drivers were political. Water sector efficiency and levels of service were considered by the public to be relatively acceptable before the reforms began” (OECD/DANCEE 2003: 11). However, the previous situation was characterised by some serious technical problems (no investment in supply systems, high losses in pipe networks, poor quality) and organisational problems (too much regulation, inadequate appraisal of consumption and prices). Domestic, industrial and agricultural water demands were permanently increasing (M INISTRY OF THE ENVIRONMENT 2003). Nevertheless it is important to mention that the Czech water infrastructure was, compared with Poland or Slovakia, of a high technical standard. Even private investors like Vivendi point out that the condition of the technology was relatively good (Interview 4). 11i 4. Restructuring of water market 4.1. Demand Following the increase in prices and the restructuring of industrial and agricultural production between 1990 and 1997 there has been a significant decrease in water consumption. The specific water consumption of households is now about 10 % below the EU average. After 1990 demand for extensive use of water resources has declined, water abstractions and water pollution also fell. Environmental factors and the role of water in the landscape and ecosystems became more important (INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON IRRIGATION AND DRAINAGE/E UROPEAN REGIONAL WORKING GROUP 1998: 35). As a result, the volume of billed (paid) water (i.e. water production without losses in the pipe network and water used by the water supply company) has decreased by 35 % since 1990 (ibid.). 4.2. Water supply and quality Maintenance of the water supply network has improved since 1990. Three quarters of the Czech population live in houses connected to public sewers and of these 5.98 million live in houses connected to public sewers with appropriate wastewater treatment (58 %). These figures are comparable to the situation in France, Spain or Greece (M INISTRY OF AGRICULTURE/M INISTRY OF THE ENVIRONMENT 2002). In 2001 public water supply systems supplied 87.3 % of the population with drinking water; 7.71 million inhabitants or 74.9 % lived in houses connected to public sewage systems. However, there exist notable regional differences with connections ranging from 100 % in Prague to 72.0 % in the Vysocina district (ibid.). The level of sewer connection is according to Consumers International about 75 % outside of Prague (CONSUMERS INTERNATIONAL 2000: 9). Water quality has improved due to the construction of new wastewater treatment plants as well as industrial restructuring. The construction of wastewater treatment plants has resulted in a decrease in organic pollution in the majority of main rivers. Although public officials like the Ministry of Agriculture claim that water quality is now similar to that in Germany, the quality in some urban/industrial centres still remains unsatisfactory (EBRD 2002: 26). 12i Development of water supply and wastewater sewerage coverage 100 water supply 90 80 wastewater disposal 01 20 99 19 97 19 95 19 93 19 91 19 89 70 19 Percentage of connected households Figure 2: Development of water supply and wastewater collection coverage 1989-2001 Source: CMKOS 2003 4.3. Prices Up until 1990 prices were uniform in all water management institutions of the Czech economy. After 1990 the management of institutions was transferred partly to the Ministry of Agriculture but primarily to towns and communities. Each institution is allowed to determine prices. Prices rose from 0,9 KCS to an average of 37,69 KCS per m3 for drinking water and wastewater (Interview 5). There exist substantial differences in prices between different regions and different institutions. For some households there have been price increases up to 190 %, for other users up to 626 % (INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON IRRIGATION AND DRAINAGE/E UROPEAN REGIONAL WORKING GROUP 1998: 145). Prices vary from 25 KCS up to 60 KCS2 per m3. Smaller companies often have lower prices because there are able to get funding. The rise in prices has not exceeded on average price increases in other sectors of the economy. Nevertheless, some sources see an increase well in excess of the rate of inflation during the 1990s (three times the rate in one year) (CONSUMERS INTERNATIONAL 2000: 10). In 2002 the prices for drinking water and wastewater were 2 From 0,80 to 1,90 Euro 13i in the Czech Republic about 80 % of the EU average (Interview 5). The prices are controlled, according to the rules of the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Environment, by the municipalities. Companies have to make a proposal regarding their costs and then the water price is calculated. The problem is that it is difficult to check the calculations of the water companies. In general prices are regarded as quite high (Interview 2). Some examples illustrate the price increases. VaK Jizni Cechy, a subsidiary of the UK-based Anglian Water, raised water rates to households by 100.7 % from 1994 to 1997, nearly double the national average. In 1999, following the company’s acquisition of the majority of the equity shares, water rates to households increased by 39.8 %, while sewage rates to households increased by 66.6 %, far higher than any other increase in the country (Public Services International, according to R UZICKA, 1999). The Ostravske VaK (OvaK), a joint-stock company of Suez and the city of Ostrava, raised the prices of drinking water for households by nearly 14 % on 1. January 2000 (EKONOMICKE ZPRAVODAJSTVI/BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY 2000). Problems with water concessions transferred to private companies often relate to prices and transparency. The Public Services International Research Unit (PSIRU) names explicitly the case of Prague (HALL/BAYLISS/LOBINA 2001). However, it is often pointed out that price increases are an important motivation for private companies to invest in the water market. 14i Figure 3: Development of water prices 1993-2002 Development of water prices 1993-2002 prices in KCS per m3 40 35 Price for drinking water supply 30 25 Price for wastewater treatment/disposal 20 15 10 Total 01 20 99 19 97 19 95 19 19 93 5 Source: CMKOS 2003 4.4. Employment The privatisation of water companies has resulted in a large reduction in jobs. From the 25.519 people employed in water supply and wastewater disposal sector in 1991 only 15.420 remained in 2002. This represents a reduction of about 40 %. It is estimated that about 15 % of the jobs were cut due to the fact that there was overemployment before 1990. But a reduction by about 25 % happened because of privatisation. Trade unions claim that privatisation makes collective bargaining more difficult. The association of employers cancelled the collective agreements for the water sector. As a result differences in payments between companies are growing. But it should be pointed out that wages in the water sector correspond with the Czech average wage. Usually employees in companies owned by multinationals are slightly better paid (Interview 5). 15i Figure 4: Employment in the Czech water sector Employment in the Czech water sector Number of employees 30000 25000 20000 15000 10000 5000 0 1991 1996 2001 2002 Source: CMKOS 2003 4.5. Investment Before 1990 investments were covered by the State. Now local authorities or private companies are to cover their own investment costs. There is an urgent need for investments: “Looking at the new water legislation, we can see that neither prices nor charges will suffice to cover the new financial requirements in the water sector relating to the implementation of the EU’s environmental acquis. About CZK 100 billion is needed for wastewater treatment plants and wastewater pipelines, and about CZK 30 billion for drinking water supply. The State Budget and foreign sources can cover approximately 30 percent of this. The remaining 70 percent of the money needed must be provided by commercial loans which means paying interest at current rates” (HAJEK/K OPACEK 2000: 51). The principal investments in the past have been to offset flood damage in 1996. These investments were mainly financed from the budget of the Czech Republic. Although there are plans for investments in the construction of new wastewater treatment 16i plants, especially in smaller towns, to improve water quality the government is continuously reducing its investment support for infrastructure. It is the government’s intention to completely cease non-returnable subsidies during the next 5 years. This will create a greater need for commercial loans, private capital investment and cost recovery through charges (OECD/DANCEE 2003: 32). New sources for investment are the EU-Phare funding programme amounting to about €61 million from 1994-2000, the ISPA applications with a contribution of €34.5 million, the EBRD and the EIB which provided in 1998 a €200 million loan to the state (ibid.). 5. Debates specific to liberalisation of water sector Basically there have been no discussions focusing solely on the water industry; instead debates have addressed privatisation in general. Because of the urgent need of money for investments in the water infrastructure, there was almost no debate about privatisation at the time: “(…) there was relatively little public interest in the water sector changes during the early 1990s”. No political parties were against water privatisation. The question was not “if there is privatisation, but privatisation to whom?” (Interview 2). Although privatisation is almost finished, a trade unionist remarks that if they had had the information about water privatisation now available they would have rejected it (Interview 5). Some commentators see a “reluctance to sell to foreigners” (PRESKETT 2001) in the Czech Republic. Many Czechs see foreign companies as exploitative, rather than operating in the best interest of the Czech Republic (ibid.). It has happened that offers of foreign investors have been rejected without a sound cause (SCHUSTER 2003). During the privatisation of the Prague Waterworks and Sewers the Prague Town Council requested the postponement of the decision surrounding the public tender owing to concern over unauthorized water prices. The typical model of privatisation – assets remaining in municipal ownership, operation by private companies – can result in private water companies not feeling responsible for the facilities. Privatisation is completed but it a regulatory framework for the water market is still required. There is no regulatory body as in the energy sector. Although originally England and Wales provided the inspiration for privatisation (OECD/DANCEE 2003: 17i 8), public officials now see England as a bad example for a privatised water market. Local authorities pinpoint the need for regulation of the social and ecological impacts of water privatisation and are afraid of losing influence over the water infrastructure (Interview 1). Critics claim, however, that “there is no water liberalisation at all” (Interview 2) because prices and concessions are highly regulated. Companies criticize the price regulation as “ridiculous” (Interview 4). Before 1990 there was a state monopoly, now there is a natural company monopoly (Interview 5). Vivendi sees the water privatisation process in the Czech Republic as a “win-win” partnership and as a good example for Central and Eastern Europe. As proof Slovakia is likely to follow the Czech model (Interview 4). Trade unionists on the other hand call the case of water privatisation in the Czech Republic a “bad example” for other countries (Interview 5). 18i 6. Emerging and future trajectories of water sector liberalisation All experts see a trend towards more private involvement. Municipalities have not enough money to act as operators, so it seems the easiest solution to privatise. CMKOS expects that in future two multinationals (Vivendi and Ondeo) will control up to 90 % of the Czech water market. The rest of the market consists of companies which are too small to be attractive for foreign investors (Interview 5). Unlike the electricity or gas sector a special regulatory office for water does not exist. The municipalities act as regulators. There is still no fixed definition of ‘water’ in the Czech constitution. Unlike in Germany, for example, water is not defined as a public good. The future of the Czech water sector depends mainly on the activities of the communities the towns and cities - and on their budgets. In the past necessary investments have been constrained by increasing fiscal deficits (EBRD 2002). There are various problems connected with the process of liberalisation and privatisation. Privatisation in general has had to struggle with the problem of corruption (CULIK 2000). The Czech Republic is ranked 45th – together with Bulgaria and Croatia – in the 2001 Corruption Perception Index by Transparency International (EBRD 2002: 24). Other problems appear because of the lack of finance to educate staff. There is a need for more experts in the municipalities. Furthermore water management policy needs to be more clearly formulated. Although experts state that “the extensive privatisation has not caused critical problems up to now” (INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON IRRIGATION AND DRAINAGE/E UROPEAN REGIONAL WORKING GROUP 1998: 173), there are several issues not solved yet. These include the ownership of water in the natural environment, ownership of river beds and the main networks of drainage structures and of irrigation networks. The powers of the Ministry of Agriculture and Ministry of the Environment are not clearly defined and a modification of juridical systems is still needed. Consumer representation is also weak. Serious problems arose in Ostrava for instance where the Regional Commercial Court decided to freeze shares of Severomoravske vodovody (SmVaK), which had been 19i sold twice (C ZECH NEWS AGENCY 1999 b). There are also conflicts between multinationals and public officials. For instance, in North Bohemia Vivendi tried to buy stakes without public bidding. The local authorities ultimately stopped this procedure. Furthermore, privatisation processes do not necessarily mean more competition: “For example, all the private concessions in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland up to 1997 were awarded without any competitive tendering process (…)” (HALL 2002: 1). Another major task is the modernisation of the legislative system and its harmonisation with the EU system. Given the limited financial resources it will be a difficult task for the Czech Republic to master these challenges. 20i 7. Key sources and other relevant information 7.1. Literature CMKOS (2003): Unpublished data on the Czech water market. CONSUMERS INTERNATIONAL (2000): Vital networks. A study of public utilities in Bulgaria, Macedonia, Czech Republic and Slovakia. Consumers International. CULIK, Jan (2000): The Profits of Privatisation. In: Central Europe Review. Vol.2, Nr. 16. CZECH N ATIONAL COMMITTEE ON LARGE DAMS (2001): Dams in the Czech Republic 2000. Lidove Noviny Publishing House: Prague. CZECH N EWS A GENCY (1999a): Anglian Water becomes majority owner of a.s. VaK Jizni Cechy. Published on 17.02.1999 in CSTK Ecoservice. (1999b): The price of water will grow with the costs of the investors. Published on 19.05.1999 in CSTK Ecoservice. (2000a): Vivendi Water expands in Czech Republic to serve Olomouc Region. Published in 30.03.2000 in Czech News Agency. (2000b): SmVaK water utility plans to gross KC 161m this year. Published in 07.01.2000 in Czech News Agency. EKONOMICKE ZPRAVODAJSTVI/BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY (2000): Water prices increased by nearly 14 % in Ostrava in January 2000. EBRD - EUROPEAN BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND D EVELOPMENT - (2002): Strategy for the Czech Republic. Under: http://www.ebrd.com/about/strategy/country/czechrep/czech.pdf. GLOBAL WATER INTELLIGENCE (2001): Prague goes to Vivendi/AWG consortium. www.globalwaterintel.com. HAJEK, MIROSLAV/KOPACEK, M IROSLAV (2000): Economic instruments and water pricing in the Czech Republic. In: The Regional Environmental Centre for Central and Eastern Europe (ed.): Economic Instruments and water pricing in Central and Eastern Europe. Szentendre, September 28-29, 2000. Conference Proceedings. Szentendre. HALL, DAVID (2002): Water in Private Hands. Commissioned by Public Services International Research Unit. University of Greenwich. London. 21i HALL, D AVID/LOBINA, EMANUELE (1999): Water and privatisation in central- und eastern Europe, 1999. Commissioned by Public Services International Research Unit. University of Greenwich. London. HALL, D./BAYLISS , K./LOBINA, E. (2001): Still fixated with privatisation: A critical Review of the world Bank’s Water Resources Sector Strategy. Paper prepared for the International Conference on Freshwater, Bonn 3-7 December 2001. Commissioned by Public Services International Research Unit. INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON IRRIGATION AND DRAINAGE/E UROPEAN REGIONAL WORKING GROUP (1998): Water Resources Management in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Lithuania, Slovenia. In: DVWK Bulletin. Nr. 21. LOBINA, EMANUELE (2001): Water privatisation and restructuring in Central and Eastern Europe, 2001. Presented at PSI seminars in Slovakia and Romania 2001. Public Services International Research Unit. LOBINA, EMANUELE/HALL, DAVID (2000): Public sector alternatives to water supply and sewage privatisation: case studies. Presented at Stockholm Water Symposium. Public Services International Research Unit. MAAßEN, H./SAUER, J./N ISSEN, T. (2002): Das Prinzip aller Dinge ist Wasser....In: Handelsblatt vom 24.06.2002 MINISTRY OF A GRICULTURE OF THE C ZECH REPUBLIC (2002): Water-supply and sewage systems in the Czech Republic 2001. Prague. MINISTRY OF A GRICULTURE/ MINISTRY OF THE ENVIRONMENT (2002): Report on the state of water management in the Czech Republic in the year 2001. Prague. MINISTRY OF THE ENVIRONMENT (2003): Water in the Czech Republic. Under: http://www.env.cz/www/zamest.nsf/defc72941c223d62c12564b30064fdcc/fcee8b02b 6505849c1256585003cbbb3? OpenDocument. Visited 24.01.2003 MLADEK, JAN: The different paths of privatisation: Czechoslovakia, 1990-? In: NATIONAL PROPERTY F UND OF C ZECH REPUBLIC (FNM CR) (2001): THE Announcement of winner of the tender of 66 per cent share of stock of Prague Waterworks and Sewers. Press Release 29.01.2001. OECD/DANCEE PROGRAMME (2003): Models of Water Utility Reform in the Central and Eastern European Countries. Swindon. PLATTNER, D ANKWART (1996): Privatisierung in der Systemtransformation. Eine ökonomische Untersuchung am Beispiel der Privatisierungspolitik in Tschechien, der Slowakei, Ungarn, Polen und Rumänien. Berlin: Arno Spitz. 1996. 22i PRESKETT, MARK (2001): Privatisation for Whom? The Czech state, citizens or foreign investors. In: Central Europe Review. Vol.3, Nr. 16. 2001. PWC-PRICEWATERHOUSECOOPERS- (2002): Privatisation Issue 17: Water and Privatisation – Some Option. www.pwcglobal.com. Visited 12.11.2002. PUBLIC SERVICES INTERNATIONAL (2000): The way forward: public sector water and sanitation. Paper hold on PSI-Briefing World Water Forum. The Hague. 17-22 March 2000. (2002): Water privatisation, corruption and exploitation. Report by Public Services International. 2002. Commissioned by Public Services International Research Unit. University of Greenwich. London. 2002. RYDAL, JIRI/PESL, IVAN (1995): The privatisation and restitution process in the Czech republic. In: Baer, B./Weiss, E. (ed.): From centrally planned to Market economy. Contribution of Land Regulation and Economics. Berlin: Schriftenreihe des DIW. 1995. RUZICKA, PAVEL (1999): Water Supply and Sewage Systems. Internal report, Water Supply and Sewage Systems. Section of the Wood, Forestry and Water Industries Workers Trade Union, Czech Republic. Prague. SCHUSTER, ROBERT (2003): Tschechien vor dem EU-Beitritt: Rum darf nicht mehr aus Kartoffeln sein. In: Le Monde diplomatique. Februar 2003. SOVAK(2002): Rocenka 2002. Jana Fucikova: Prague. STATUE BOOK NO. 274/2001 (2001): Act on water supply systems and sewage and draining systems for public use and on change of certain acts (Act on water supply systems and sewage systems) SUEZ LYONAISSE DES EAUX GROUP (1999): Suez Lyonaisse des Eaux strenghtens its position in the Czech Water Market. Press Release published on 07.10.1999. TOMASEK, MARCEL (2001): Privatization, Post-privatization and the Rule of Law in the Czech Republic. In: WeltTrends. Nr. 31. S. 31-43. VIVENDI ENVIRONMENT (2000): Vivendi Water expands in Czech water market and strengthens its position as leader. In: Vivendi Press Release. Published on 21.03.2000. VIVENDI ENVIRONMENT (2001): Vivendi Environment increases business in Czech Republic’s industrial market. In: Vivendi PR. Published on 01.08.2001 WANNER, J IRÍ (2000): Wastewater Treatment in the Czech Republic. In: Korrespondenz Abwasser. Vol. 45. No. 10. pp. 1909-1921. 23i 7.2. Web resources European Bank for Reconstruction and Development- http://www.ebrd.com Ministry of the Environment of the Czech Republic – http://www.env.cz National Property Fund of the Czech Republic (FNM CR) – http://www.fnm.cz 7.3. Expert interviews 1) Ministry of Agriculture, Department of Water Management Policy, Ministry of Agriculture, Department of Water Supply and Wastewater Sewage – Prague, 31st March 2003 2) Water Supply and Sewer Association CZ/Sdruzeni oboru vodovodu a kanalizaci CR (SOVAK) - Prague, 31st March 2003 3) Liberalni Institut Praha, Research Fellow - Prague, 1st April 2003 4) VIVENDI Water Czech Republic, Managing Director for Europe Central – Prague, 2nd April 2003 5) Chief of the Water Supplies Commission of the affiliated Trade Union of Workers in the Woodworking Industry, Forestry and Management of Water Supplies – Prague, 3rd April 2003 24i