Phase I Report - Center for Evidence

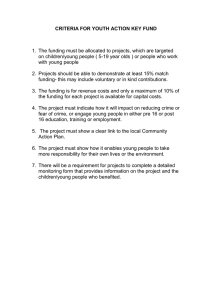

advertisement