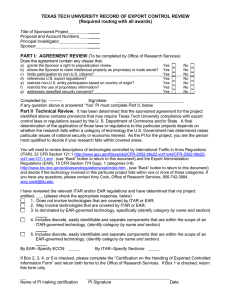

Export Controls and Universities

advertisement