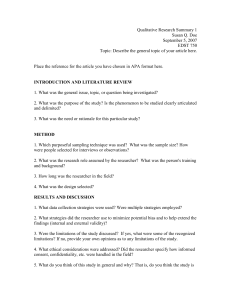

Understanding research philosophies and approaches

advertisement