THE PROTECTION OF PRE-REGISTRATION RIGHTS IN LAND: A

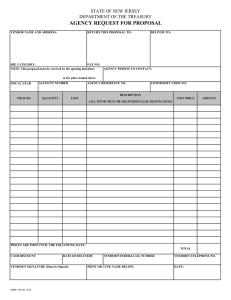

advertisement