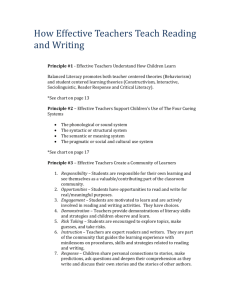

Scarsdale Elementary Schools

advertisement