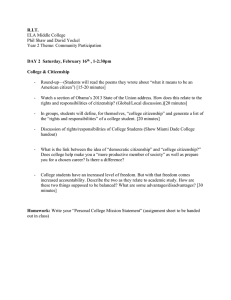

(C) Emerald Group Publishing Limited

advertisement