Wheelchair Seated Posture Measurement in a Clinical Setting

ISO 16840 Part 1

Posture Measurement Standard

Summary and Proposed Changes

ISS 2014

Vancouver, Canada

Purpose of this session:

• Introduce ISO 16840-1/ background

• Describe ISO 16840-1 (2006)

• Review some proposed changes to ISO

16840-1

16840

1 (Voting to take place in 2014)

Barbara Crane PT, PhD, ATP/SMS

Associate Professor

University of Hartford

West Hartford, Connecticut, USA

bcrane@hartford.edu

We need different terms for

the body, the seating supports,

and the wheelchair

Why do we need a standard?

• Variation in terms and measures

– In clinical practice

– In research

– By manufacturers of equipment

• Body and support surface measures are usually

different – need to communicate clearly

– Example: Buttock/thigh depth vs

vs. Seat depth

• Communication barriers

– Inefficiency in service delivery

– Poor outcomes for patients

• Wheelchair frame and support surface

measures also frequently different

• Interferes with research

– Example: Seat depth vs. Wheelchair seat pan depth

– Note – Wheelchair frame dimensions are NOT in

16840-1

– Difficult to understand studies

– Difficult to compare results of studies

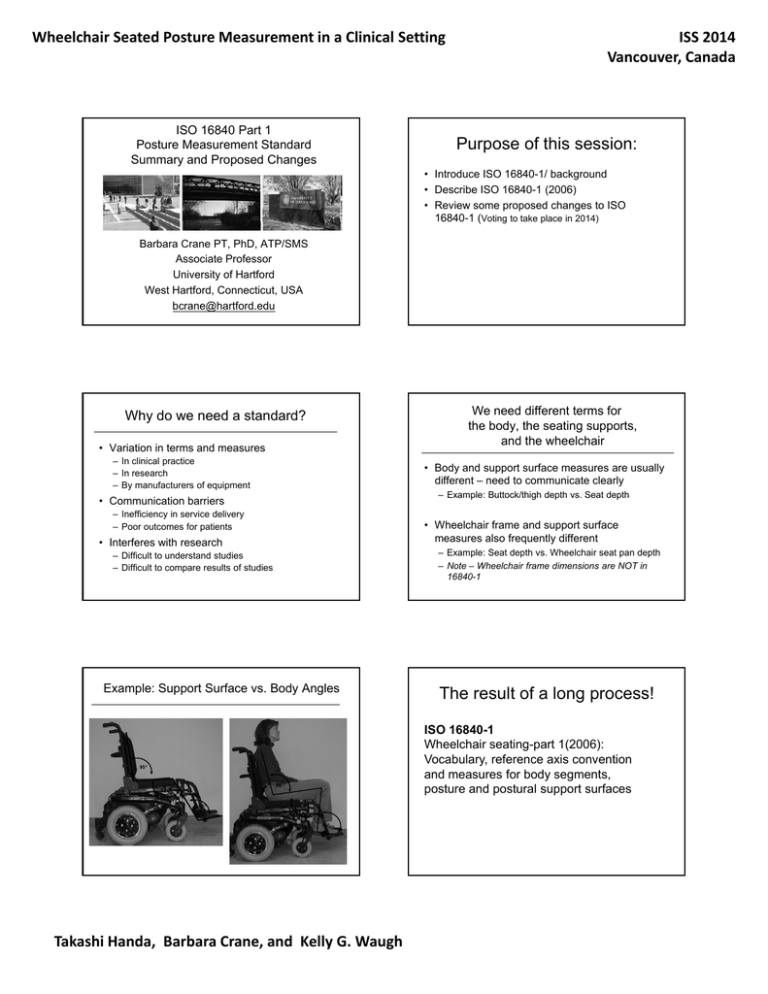

Example: Support Surface vs. Body Angles

ISO 16840-1

Wheelchair seating-part 1(2006):

Vocabulary, reference axis convention

and

d measures ffor body

b d segments,

t

posture and postural support surfaces

95°

98°

120°

105°

The result of a long process!

75°

95°

Takashi Handa, Barbara Crane, and Kelly G. Waugh

Wheelchair Seated Posture Measurement in a Clinical Setting

ISO 16840-1: 2006

ISO 16840-1 Evolution

ISO 16840-1

(2006)

Revision

Development of

Clinical Guide

(2013)

• Describes a global coordinate system

– Coordinate system conventions (rules)

– Multiple axis systems

• Defines measures of the seating support surfaces:

– Support surface angles (absolute and relative)

– Linear size measures

– Linear location measures

• Defines measures of the seated person:

– Body angles (absolute and relative)

– Linear size measures

Coordinate System Conventions

(Proposed)

• Right hand rule for axes

– Establishes positive direction for each axis

– New orientation for right hand (moves axes)

• Z

Y; Y

X; X

ISS 2014

Vancouver, Canada

Axes – Right Hand Rule

Current RHR

Proposed RHR

(first finger points to the right)

(thumb points to the right)

Z

• Three orthogonal planes

– Changes in which axes make up planes due

to changes to axes

• Right hand grip rule for direction of rotation

– Clockwise rotation negative

Current:

Axes and Planes

Coordinate System Components

(Proposed)

• Global coordinate system

– Origin external to body and support surfaces

• located on the floor

• Reference axis systems

Proposed:

Sagittal

(right side)

Frontal

Transverse

–

–

–

–

Wheelchair Axis System (may use as global)

Support Surface Axis System (and SSRP)

Seated Anatomical Axis System (and SRP)

Local Axis System

• For each body segment

• For each postural support

Takashi Handa, Barbara Crane, and Kelly G. Waugh

Wheelchair Seated Posture Measurement in a Clinical Setting

Wheelchair Axis System

Current:

ISS 2014

Vancouver, Canada

Support Surface Axis System

Current:

P

Proposed:

d

Proposed:

Seated Anatomical Axis System

Current:

Local Axis Systems

(Proposed)

Proposed:

Measuring Absolute Angles

Current:

“Compass Rose” system

(Left Hand Grip Rule)

clockwise positive

Proposed: Right Hand Grip Rule – clockwise negative

Takashi Handa, Barbara Crane, and Kelly G. Waugh

Current Absolute Angles

Uses Compass Rose (left hand grip rule), and

Body Segment Lines, vertical is zero,

Clockwise rotation is positive

Wheelchair Seated Posture Measurement in a Clinical Setting

Proposed Absolute Angles

Uses right hand grip rule and local axes

Clockwise is negative

Summary of Proposed Changes

• Changes in axes

• Changes in absolute angles

– Use of local axis system

• Reference positions are zero

• No more reference lines for support surfaces needed

• Changes

Ch

iin relative

l ti angles

l

– Thigh to lower leg

– Seat to lower leg support

Takashi Handa, Barbara Crane, and Kelly G. Waugh

ISS 2014

Vancouver, Canada

Relative Body Segment Angles

Current

Thigh to Lower Leg

Proposed

Thigh to Lower Leg

How does a standard help us?

• Development of new measuring methods

– Focus on sitting posture

– Better linear dimensions of person, postural

supports and wheelchair

• Development of new measuring tools

– Rysis

– Horizon

Standardized Seating Measurement: Introduction to a Clinical Guide

12/14/2012

Colorado, USA

A Clinical Application Guide to

the ISO 16840-1 Standard

Kelly Waugh, PT, MAPT, ATP

Senior Instructor/Clinic Coordinator

Assistive Technology Partners

University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus

Denver, Colorado, USA

Colorado is known for its

beautiful Rocky Mountains!!

Copyright © 2014, The Regents of the University of Colorado, a body corporate. All rights reserved.

Created by Kelly Waugh, Assistive Technology Partners; supported by Grant #668 from the PVA Education Foundation

A Clinical Application Guide to the ISO

16840-1 Standard

1. Background

2. Overview of the Clinical Application Guide

3. Angular Measures of the Body

Background

ISO 16840-1 published in 2006

Costly to purchase

Difficult to understand and apply clinically

2011-2013: Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA) Education

Foundation grant

Funded development of two new free resources, based on the

ISO standard:

1. A clinical application guide to the ISO standard

2. A glossary of wheelchair terms and definitions

Both are available on our website

http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/medicalschool/programs/atp/Resource

s/WheelchairSeating/Pages/WheelchairSeating.aspx

A Clinical Application Guide to Standardized

Wheelchair Seating Measures of the Body and

Seating Support Surfaces, Revised Edition

A Clinical Application Guide to the ISO

16840-1 Standard

1. Background

• Initially published in February 2013

2. Overview of the Clinical Application Guide

• Revised Edition posted July 2013

– Axis convention changed; Right hand grip rule reversed positive

and negative values for absolute angles

3. Angular Measures of the Body

• Updated November 2013

– Minor corrections made to cover page and page 43

• Japanese and Korean translations are under way!

Kelly Waugh, PT, MAPT

1

Standardized Seating Measurement: Introduction to a Clinical Guide

What is the purpose of the Clinical Guide?

12/14/2012

What is included in the Clinical Guide?

1. “Translate” the content of ISO 16840-1 standard into a resource

manual that is easy to understand and apply clinically

1. Explains foundational principles upon which the terms

and measures are based

2. Make the guide available on internet in PDF format, which is free

to download, so that everyone has access to it.

2. Defines terms for measures of the seated person

The main goal:

• Promote the adoption of standardized terms and measures in the

field of wheelchair seating

3. Defines terms for measures of seating support surfaces

How is the content of the Clinical Guide different

from the ISO Standard?

Angular Body Measures

Linear Body Measures

Angular Support Surface Measures

Linear Support Surface Measures

Does not included Linear Location Measures

Table of Contents of the Clinical Guide

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

•

•

The ISO standard includes only a definition of each measurement

term

Only talking about Angular Body

Measures in this presentation!

CHAPTER 2: ANGULAR BODY MEASURES

CHAPTER 3: ANGULAR SUPPORT SURFACE MEASURES

The Clinical Guide also includes:

– Simple description

– Sample measurement procedure

– Lots of diagrams

– Clinical relevance of measure

CHAPTER 4: LINEAR BODY MEASURES

CHAPTER 5: LINEAR SUPPORT SURFACE MEASURES

APPENDICES (4)

GLOSSARY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A Clinical Application Guide to the ISO

16840-1 Standard

3

Angular Measures of the Body

Basic Concepts

Relative vs. Absolute Angles

Examples of Relative Angles

Examples of Absolute Angles

1. Background

2. Overview of the Clinical Application Guide

3. Angular Measures of the Body

Angular measures of the body

describe person’s seated posture

Kelly Waugh, PT, MAPT

2

Standardized Seating Measurement: Introduction to a Clinical Guide

12/14/2012

Why measure wheelchair seated posture?

Why measure wheelchair seated posture?

1. Helps with assessment and prescription

– Correlation of body angles to seating angles helps with clinical

problem solving

4. Justify need and cost of complex or custom seating system

5. Track postural change over time

2. Set measurable postural objectives

– Measure “current” posture (baseline)

– Document “desired” posture (goal) based on clinical assessment

3. Document outcomes

– Measure posture before and after seating intervention

Describing wheelchair seated posture using joint

motion terminology is not adequate for our field

Currently, therapists use joint motion terms to describe sitting

posture

“Mrs. Jones is sitting with hips extended, trunk laterally flexed to

the left, and legs abducted”

This is not adequate for wheelchair seating because

Joint motion terms are frequently used inaccurately

Joint motion terms do not help prescribe orientation of

seating supports

Joint motion terms do not describe orientation in space of

body segments

The Three Reference Planes

6. RESEARCH

– To investigate relationships between seated posture and

functional outcomes, we need to be able to measure seated

posture in a consistent and reliable manner

Next…..How do we describe, measure and document wheelchair seated posture?

The standard provides a different way to measure

seated posture using body segment angles

This method of seated posture measurement:

Views postural deviations in three planes

Divides body into segments

Identifies body landmarks on each segment

Connects landmarks with imaginary line

Measures orientation of the body segment line in two ways:

With respect to adjacent segment

With respect to gravity

Postural deviations in sitting position can be described in

each of these same three reference planes

Body movement defined by:

1. The plane through which the

body limb moves

• Sagittal

• Frontal

• Transverse

2. For example, flexion/extension

occurs in sagittal plane

The “Standing Anatomical

Position” is the zero reference

for joint range of motion values

Kelly Waugh, PT, MAPT

• Three perspectives:

• SIDE

SAGITTAL plane deviations

• FRONT

FRONTAL plane deviations

• TOP

TRANSVERSE plane deviations

3

Standardized Seating Measurement: Introduction to a Clinical Guide

Body is divided into segments

Body

Landmarks

Dividing body into segments allows

us to:

• Describe seated posture by

measuring orientation of body

segments instead of joint

position

•

12/14/2012

Relate orientation of body

segments to the orientation of

their supporting surface

Body landmarks

were identified

on each

segment that

can be viewed

from side, front

and top

How can we measure the

orientation of the body segments?

Body

Segment

Lines

3

Lines connecting

the body landmarks

are called Body

Segment Lines.

The lines are used

to measure the

angular

orientation of the

segments in each

plane.

By measuring the angular

orientation of body

segments, you can define

the static posture of seated

person. The angles

formed are called body

segment angles.

Relative vs. Absolute Angles

THERE ARE TWO DIFFERENT TYPES OF ANGULAR MEASURES:

• Relative angles define the angular relationship between two

adjacent body segments

• Reflects joint position

• Absolute angles define the orientation of a single body segment

with respect to an external, absolute reference such as the vertical or

horizontal

• Reflects orientation in space

Kelly Waugh, PT, MAPT

Angular Measures of the Body

Basic Concepts

Relative vs. Absolute Angles

Examples of Relative Angles

Examples of Absolute Angles

Example of a relative angle

The angle of the trunk relative to the

thigh is called the Thigh to Trunk Angle.

Important because it reflects how much

hip flexion she is sitting in, which may

impact spinal posture, muscle tone or

comfort

Thigh to trunk angle = 105 degrees

Does the 105 degree thigh to trunk angle

give you information on the orientation in

space of her trunk or thigh?

4

Standardized Seating Measurement: Introduction to a Clinical Guide

Absolute angles give information on orientation in space

12/14/2012

Absolute angles give information on orientation in space

vertical

The orientation in space of her trunk is

important because it affects her

balance and functional reach

The slope of her thigh is important

because it may affect stability on seat

Sagittal trunk angle

= +5 degrees

The sagittal thigh angle measures the

orientation in space of her thigh

relative to the horizontal, in the sagittal

plane

The Sagittal Trunk Angle measures the

angle of the trunk with respect to the

vertical, in the sagittal plane

horizontal

Sagittal thigh angle = -15 degrees

Absolute angles can change without a change in relative

angle

3

Angular Measures of the Body

Basic Concepts

Relative vs. Absolute Angles

Examples of Relative Angles

Examples of Absolute Angles

THI/TK=105°

THI/TK=105°

THI-sag = 0°

THI-sag = -15°

Thigh to trunk angle (THI/TK) is the same

Sagittal thigh angle (THI-sag) is different

Thigh to trunk angle

Relationship to hip flexion angle

Relative body segment angles

•

Relative body segment angles measure the angle between adjacent segments

The angle between the thigh

and the trunk, viewed from the

side

Kelly Waugh, PT, MAPT

The angle between the thigh

and the lower leg, viewed from

the side

The angle between the lower

leg and the foot, viewed from

the side

The angle between the thigh and the

trunk, viewed from the side

More useful for

prescribing desired seat

to back support angle

…relationship to hip flexion

angle

5

Standardized Seating Measurement: Introduction to a Clinical Guide

3

Angular Measures of the Body

Examples of Absolute Body Segment Angles

Level I

Basic Concepts

Relative vs. Absolute Angles

Examples of Relative Angles

Examples of Absolute Angles

Sagittal Pelvic Angle

Sagittal Trunk Angle

Sagittal Thigh Angle

Sagittal Head Angle

Sagittal Upper Trunk Angle

Sagittal Sternal Angle

Sagittal Abdominal Angle

Sagittal Lower Leg Angle

Sagittal Foot Angle

Frontal plane

Frontal Pelvic Angle

Frontal Sternal Angle

Frontal Trunk Angle

Frontal Head Angle

Frontal Lower Leg Angle

Frontal Foot Angle

Transverse plane

Transverse Pelvic Angle

Transverse Trunk Angle

Transverse Head Angle

Transverse Thigh Angle

Transverse Foot Angle

Sagittal body segment angles measure the orientation of a single body segment in the

sagittal plane with respect to either the horizontal or vertical

SAGITTAL THIGH ANGLE

The angle of the trunk with

respect to the vertical, viewed

from the side

The angle of the pelvis with

respect to the horizontal,

viewed from the side

Kelly Waugh, PT, MAPT

‐ 15 degrees

•

How to define if thigh is rotated

upward or downward relative to

the horizontal?

•

Use positive and negative

numbers to indicate direction of

rotation away from reference axis

•

“Right hand grip rule” defines

positive and negative direction of

rotation away from zero reference

The angle of the thigh with

respect to the horizontal,

viewed from the side

Right Hand

Grip Rule

SAGITTAL THIGH ANGLE

Level II

Sagittal plane

Positive or negative value indicates direction of

rotation from zero reference position

Sagittal absolute body segment angles

•

12/14/2012

Frontal absolute body segment angles

•

•

Point thumb of your right hand along the

axis of rotation for plane in which the

angle lies

•

Axis of rotation is always perpendicular

to the plane

•

The direction that your fingers curl

around your thumb is the positive

direction.

‐ 15 •

degrees

Counterclockwise is positive when

viewing person from right side, front and

top

Frontal body segment angles measure the orientation of the body segment in the

frontal plane with respect to either the horizontal or vertical

The angle of the sternum with

respect to the vertical, viewed

from the front

The angle of the pelvis with

respect to the horizontal,

viewed from the front

The angle of the whole trunk

with respect to the vertical,

viewed from the front

6

Standardized Seating Measurement: Introduction to a Clinical Guide

Transverse absolute body segment angles

•

Transverse body segment angles measure the orientation of the body segment in the

transverse plane with respect to either the wheelchair X or Z axis

The angle of the trunk with

respect to the wheelchair,

viewed from the top

The angle of the pelvis with

respect to the wheelchair,

viewed from the top

12/14/2012

Summary

By measuring the angular orientation of body segments in

each plane you can define the static posture of a seated

person. These are called body segment angles

The corresponding angular measures of the seating support

system are called support surface angles.

The same conventions are used to measure body segment

angles and support surface angles - helps with prescription.

There is a free clinical guide to help you learn about these

measures.

The angle of the thigh with

respect to the wheelchair,

viewed from the top

Practicum

LET’S PRACTICE SOME MEASURES!

Kelly Waugh, PT, MAPT

7

Practice: Thigh to Trunk Angle

THIGH TO TRUNK ANGLE

Type of Measurement: Relative body segment angle,

right and left

Description: The angle between the thigh and the trunk,

viewed from the side.

Landmarks used:

• Lateral hip center point (center of rotation)

• Lateral femoral condyle

• Lateral lower neck point

Body segment lines used to form angle:

• Sagittal trunk line

• Sagittal thigh line

Angle measured: The anterior side of the angle formed

between the sagittal trunk line and the sagittal thigh line.

SRP Value: 90 degrees

Typical Values: 90 – 120

Practice: Thigh to Lower Leg Angle

THIGH TO LOWER LEG ANGLE

Type of Measurement: Relative body segment angle,

right and left

Description: The angle between the thigh and the lower

leg, viewed from the side.

Landmarks used:

• Lateral femoral condyle (center of rotation)

• Lateral hip center point

• Lateral malleolus

Body segment lines used to form angle:

• Sagittal thigh line

• Sagittal lower leg line

Angle measured: The posterior side of the angle formed

between the sagittal thigh line and the sagittal lower leg

line.

SRP Value: 90 degrees

Typical Values: 80 – 120

Practice: Sagittal Trunk Angle

SAGITTAL TRUNK ANGLE

Type of Measurement: Absolute body segment

angle

Description: The angle of orientation of the

trunk with respect to the vertical, viewed from

the side.

Landmarks used:

• Lateral lower neck point

• Lateral hip center point

Lines used to form angle:

• Vertical (YWAS)

• Sagittal trunk line

Angle definition: Degree of rotation from the

vertical (YWAS) to the sagittal trunk line, viewed

from the side and projected to the sagittal plane

Practice: Sagittal Pelvic Angle

SAGITTAL PELVIC ANGLE

Type of Measurement: Absolute body segment

angle

Description: The angle of orientation of the

pelvis with respect to the horizontal, viewed

from the side.

Landmarks used:

• ASIS

• PSIS

Lines used to form angle:

• Horizontal (XWAS)

• Sagittal pelvic line

Angle definition: Degree of rotation from the

horizontal (XWAS) to the sagittal pelvic line,

viewed from the side and projected to the

sagittal plane.

Practice: Sagittal Thigh Angle

SAGITTAL THIGH ANGLE

Type of Measurement: Absolute body segment

angle, right and left

Description: The angle of orientation of the

thigh in the sagittal plane, with respect to the

horizontal.

Landmarks used:

• Lateral hip center point

• Lateral femoral condyle

Lines used to form angle:

• Horizontal (XWAS)

• Sagittal thigh line

Angle defined: Degree of rotation from the

horizontal (XWAS) to the sagittal thigh line,

viewed from the side and projected to the

sagittal plane.

Practice: Frontal Sternal Angle

FRONTAL STERNAL ANGLE

Type of Angle: Absolute body segment angle

Description: The angle of orientation of the

upper trunk with respect to the vertical, viewed

from the front.

Landmarks used:

• Upper sternal notch

• Lower sternal notch

Lines used to form angle:

• Vertical (YWAS)

• Frontal sternal line

Angle definition: Degree of rotation from the

vertical (YWAS) to the frontal sternum line,

viewed from the front and projected to the

frontal plane.

Practice: Frontal Pelvic Angle

FRONTAL PELVIC ANGLE

Type of Angle: Absolute body segment angle

Description: The angle of orientation of the

pelvis with respect to the horizontal, viewed

from the front.

Landmarks used:

• Right ASIS

• Left ASIS

Lines used to form angle:

• Horizontal (ZWAS)

• Frontal pelvic line

Angle definition: Degree of rotation from the

horizontal (ZWAS) to the frontal pelvic line,

viewed from the front and projected to the

frontal plane.

Practice: Transverse Pelvic Angle

TRANSVERSE PELVIC ANGLE

Type of Angle: Absolute body segment angle

Description: The angle of orientation of the

pelvis in the transverse plane with respect to the

wheelchair frame, viewed from the top.

Landmarks used:

• Right ASIS

• Left ASIS

Lines used to form angle:

• Wheelchair Z-axis (ZWAS)

• Transverse pelvic line

Angle defined: Degree of rotation from the

Wheelchair Z-axis (ZWAS) to the transverse

pelvic line, viewed from the top and projected to

the transverse plane.

Practice: Transverse Thigh Angle

TRANSVERSE THIGH ANGLE

Type of Measurement: Absolute body

segment angle, left and right

Description: The angle of orientation of the

thigh in the transverse plane with respect to

the wheelchair, viewed from the top.

Landmarks used:

• ASIS

• Superior knee point

Lines used to form angle:

• Wheelchair X-axis (X WAS)

• Transverse thigh line

Angle defined: The degree of rotation from

the wheelchair X-axis (X WAS) to the

transverse thigh line, viewed from the top and

projected to the transverse plane.