Introduction to education project planning and - unesdoc

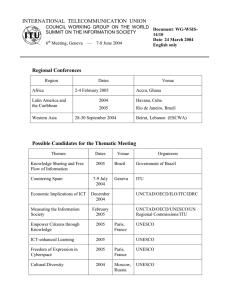

advertisement