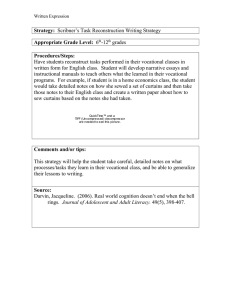

Observing vocational practice: a critical investigation of the use and

advertisement