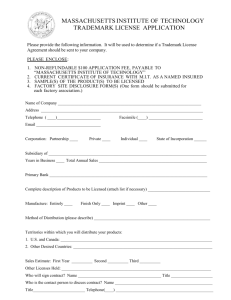

trademarks in business transactions

advertisement