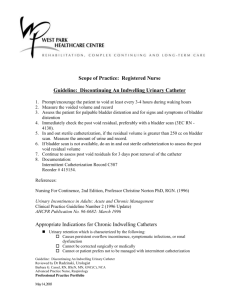

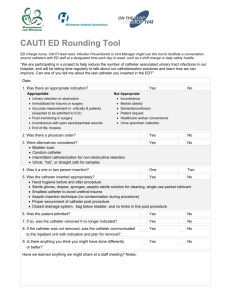

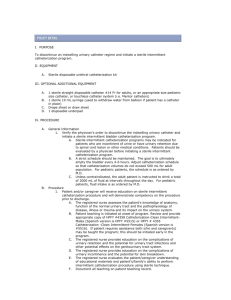

Review of Intermittent Catheterization and Current Best Practices

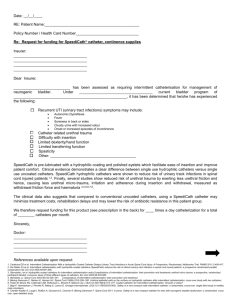

advertisement