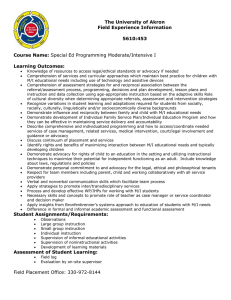

Monitoring and Evaluating Advocacy

advertisement