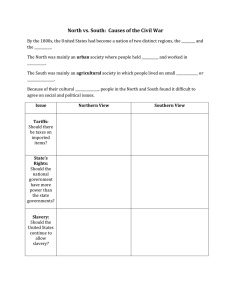

The Global Slavery Index 2013 - United Nations Global Initiative to

advertisement