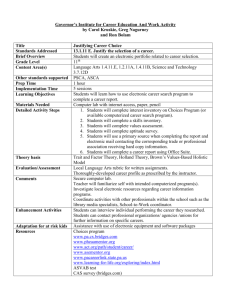

Cambridge Law Journal Trumping Bolam: a critical legal analysis of

advertisement