Gap regulation for suspended rotating disks in microgyroscopes

advertisement

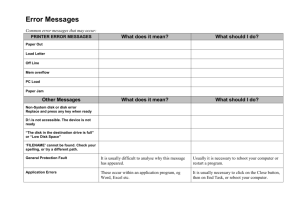

10.1117/2.1201001.002565 Gap regulation for suspended rotating disks in microgyroscopes Nan-Chyuan Tsai, Bing-Hong Liou, and Chih-Che Lin An innovative micromagnetic height adjuster serves as both actuator and sensor. Microactuators (the power supply in small machines) play an important role in microelectromechanical systems (MEMS). Electrostatic combs, for example, provide linear motion. Magnetic actuators are particularly interesting because of their controllability. They have been studied for years. Yet the drive power of the typical planar-coil design1 in such devices is extremely limited. Moreover, the practical fabrication process is imperfect, giving rise to problems such as undesired bubbles or cavities inside a microsolenoid (looped structure) coil.2 To overcome the disadvantages of the traditional design, we propose an innovative pyramidal solenoid that performs the dual functions of actuator and sensor. The magnetic module is basically similar to a microscale linear variable differential transformer (LVDT), which actively adjusts the height of the rotating seismic disk used in a gyroscope. When the microgyroscope is subjected to an angular excitation (x or y axis) that is perpendicular to the principal spinning axis (z axis), the pitch angle (x or y axis) of the rotating disk responds accordingly. Because of the Coriolis effect (an artifact of the earth’s rotation), this induced pitched motion can be used to estimate the angular rate exerted. We designed a micromagnetic height adjuster (MMHA) for microgyroscopes that consists of four identical LVDT pairs, distributed evenly 90◦ apart in a circle.3, 4 Each pair contains two sets of LVDTs, one above and the other below the disk. Each LVDT set comprises three pyramids (see Figure 1) whose primary winding is located between two secondary windings. The rotating disk is sandwiched between four LVDT pairs (see Figure 2). The nominal gap between the rotating disk and the LVDT is set at 10µm. The key role of the primary winding is to regulate the gap change when it is perturbed by disk-mass eccentricity or Figure 1. Individual set of micromagnetic height adjusters (MMHAs). Figure 2. Rotating disk sandwiched between four pairs of MMHAs. other disturbances. The embedded controller of the microgyroscope determines how much electric current needs to be applied at the primary winding, based on the gap change measured by the secondary windings. In other words, the primary winding behaves like a magnetic actuator, and the secondary windings like magnetic sensors. The geometry and dimensions of the primary winding consist of a substrate, an electro-formed coil, and an iron core, which en- Continued on next page 10.1117/2.1201001.002565 Page 2/3 Figure 3. Top (a) and side (b) views of a pyramidal solenoid. a: Distance between O and the coil along the x or y direction. d: Differentiation. γ: Angle between the x-y plane and the pyramidal surface. h: Height of the rotating disk above the solenoid. I: Applied current. P: Center of the disk at equilibrium. w: Distance between two adjacent coil layers. Figure 5. (a) Magnetic-flux distribution at the secondary windings as the disk is displaced by −5µm. (b) Impedance variation at the secondary windings versus position deviation of the disk. In summary, the magnetic force induced by the primary winding (actuator) is greatly enhanced by including an iron core located at the center of a pyramid-like 3D coil winding. The secondary windings (gap sensors) estimate the gap change by virtue of the eddy-current effect. These results confirm our preliminary finding of a dual capability of actuation and sensing for the MMHA. As a next step, we plan to test the performance of the device in integrated applications. Author Information Figure 4. Magnetic-field distribution. able the resulting magnetic force to reach on the order of microNewtons or above. The top view of each coil layer resembles a square: see Figure 3(a). Theoretically, the induced magnetic force is in the direction of the z axis. Using the commercial software package Maxwell Ansoft,5 we determined the highest flux density at the middle of the triplet to be approximately 30–40mTesla, which is sufficient to attract the disk laterally, that is, in the direction of the z axis (see Figure 4). We note that the resultant magnetic force is proportional to the square of the applied coil current and the inverse of the square of the distance. The role of the second windings is simply to measure the gap change between the rotating disk and the MMHA. Supplying AC to the secondary windings induces an electrical signal when the disk tilts by virtue of the so-called eddy-current effect. As the gap between the disk and the MMHA changes, the intensity of the eddy current alters accordingly, which in turn affects the impedance of the secondary windings (see Figure 5). Nan-Chyuan Tsai, Bing-Hong Liou, and Chih-Che Lin National Cheng Kung University Tainan City, Taiwan Nan-Chyuan Tsai was born in Taiwan in 1963. He received his PhD in mechanical engineering from the Pennsylvania State University in 1995. Since 2007 he has been an associate professor at the National Cheng Kung University. His research interests include microsystems technology, control engineering, and active magnetic bearings. Bing-Hong Liou was born in Taiwan in 1983. He received his BS in 2007 from the National Cheng Kung University, where he is also about to earn his MS in MEMS/NEMS (nanoelectromechanical systems) technologies. His research interests include design and fabrication of MEMS/NEMS devices. Chih-Che Lin was born in Taiwan in 1983. He received his MS in 2008 from the National Cheng Kung University, where he will soon earn his PhD in MEMS/NEMS technologies. His reContinued on next page 10.1117/2.1201001.002565 Page 3/3 search interests include design and fabrication of MEMS/NEMS devices. References 1. A. Beyzavi and N. T. Nguyen, Modeling and optimization of planar microcoils, J. Micromech. Microeng. 18 (9), p. 095018, 2008. doi:10.1088/0960-1317/18/9/095018. 2. C. H. Ahn and M. G. Allen, A comparison of two micromachined inductors (bar- and meander-type) for fully integrated boost DC-DC power converters, IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 11 (2), pp. 239–245, 1996. doi:10.1109/63.486171. 3. N. C. Tsai and C. Y. Sue, Fabrication and analysis of a micro-machined triaxis gyroscope, J. Micromech. Microeng. 18, p. 115014, 2008. doi:10.1088/09601317/18/11/115014 4. N. C. Tsai, B. . H. Liou, and C. C. Lin, Gap regulation for suspended rotating disc used for micro-gyroscopes, J. Micro/Nanolithogr. MEMS MOEMS 8, p. 043045, 2009. doi:10.1117/1.3256005 5. http://www.ansoft.com/ Electronic design automation software company. Accessed 4 January 2010. c 2010 SPIE