Nova Scotia`s Trade Strategy with China By Zhenya Guo A research

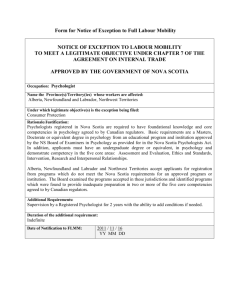

advertisement