Wisconsin Strategic Highway Safety Plan

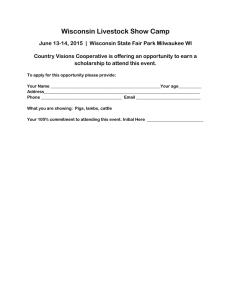

advertisement