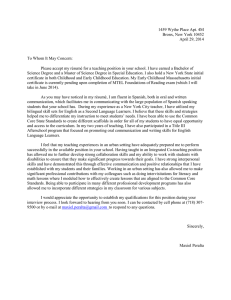

Supporting Children Learning English as a Second language in the

advertisement