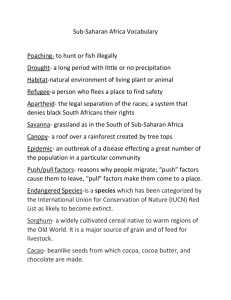

Small-scale versus large-scale cocoa farming in Cameroon

advertisement