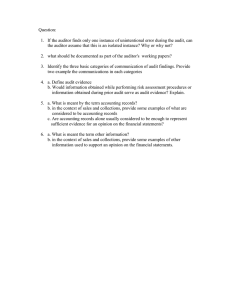

Audit planning I

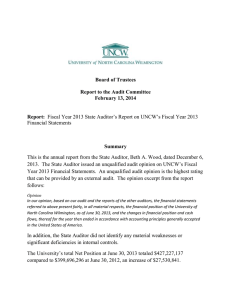

advertisement