DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

Arrhythmic Mitral Valve Prolapse and Sudden Cardiac Death

Running title: Basso et al.; Arrhythmic Mitral Valve Prolapse

Cristina Basso, MD, PhD1*; Martina Perazzolo Marra, MD, PhD1*; Stefania Rizzo, MD, PhD1;

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

Manuel De Lazzari, MD, PhD1; Benedetta Giorgi, MD2; Alberto Cipriani, MD1; Anna Chiara

Frigo,

g MSc1; Ilaria Rigato,

g

MD, PhD1; Federico Migliore,

g

MD, PhD1; Kalliopi

p Pilichou, PhD1;

Emanuele Bertaglia, MD1; Luisa Cacciavillani, MD, PhD1; Barbara Bauce, M

MD,

D, P

PhD

hD1;

Domenico Corrado, MD, PhD1; Gaetano Thiene, MD1; Sabino Iliceto, MD1

1

Dept

Dep

De

pt of Ca

Cardiac, Thoracic, and Vascular Scienc

Sciences;

cess; 2Dept of Ra

Radiology,

adi

d ology, Azienda OspedalieraUniv

versity of Padua

Padua Medical

Pa

Mediicaal School,

Scho

Sc

hoool, Padua,

ho

Padu

dua, Italy

du

Itaaly

y

University

*contributed

*con

*c

ontr

on

trib

tr

ibut

ib

uted

ut

ed eequally

qual

qu

ally

al

ly

Address for Correspondence:

Cristina Basso, MD, PhD

Department of Cardiac, Thoracic, and Vascular Sciences

University of Padua Medical School

Via A. Gabelli, 61

35121 Padova-Italy

Tel: +39 0498272286

Fax: +39 0498272284

Email: cristina.basso@unipd.it

Journal Subject Codes: Diagnostic testing:[30] CT and MRI, Etiology:[5] Arrhythmias, clinical

electrophysiology, drugs

1

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

Abstract

Background—Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) may present with ventricular arrhythmias and

sudden cardiac death (SCD) even in the absence of hemodynamic impairment. The structural

basis of ventricular electrical instability remains elusive.

Methods and Results—A) The Cardiac Registry of 650 young adults (40 yrs) with SCD was

reviewed and cases with MVP as the only cause of SCD were reexamined. Forty-three MVP

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

cases (26 female, age range 19-40, median 32 yrs) were identified (7% of all SCD, 13% of

women). Among 12 with available ECG, 10 (83%) had inverted T waves on inferior leads and all

right

found

ight bundle branch block ventricular arrhythmias. A bileaflet involvement was fo

oun

undd in 770%.

0%.

0%

LV fibrosis was detected at histology at the level of papillary muscles in all and infero-basal wal

wall

in

88%.

MVP

ventricular

n 88%

8%.. B) M

8%

VP

P ppatients

atients with complex ventricu

ula

larr arrhythmias (N=30)

0)) aand

nd without (controls,

N=14)

underwent

study

protocol

cardiac

magnetic

N=114) underwen

ent a st

en

stud

udyy pr

ud

prot

otoocol

ot

ocol

o iincluding

nclu

nc

luding

ng

g ccontrast-enhanced

ontra

rast-eenh

ra

nhan

ancced

an

ced ca

card

rdia

rd

iacc m

ia

agn

gnet

gn

etic

et

ic rresonance

eson

es

onnan

ance

ce ((CECECE

CMR).

Patients

with

arrhythmias

(22

age

28-43,

median

CM

MR)

R). Patien

ents w

en

ith ccomplex

om

mpleex ve

vventricular

nttri

ricu

ulaar ar

rrh

rhyt

ythm

mias (2

22 ffemale,

ema

male

ma

lee, ag

ge rrange

anngee 28

28-43

3, m

3,

ed

diaan 41

yrs),

either

branch

polymorphic,

yrrs)

yrs)

s), ei

eith

ther

th

er rright

ight

ig

ht bbundle

un

undl

ndl

dlee br

bran

anch

an

ch bblock-type

loc

ockk-ty

type

pe oorr po

poly

lymo

morp

mo

rphi

rp

hicc, sshowed

hi

howed

ho

ed a bbileaflet

ilea

il

eafl

ea

flet

fl

et iinvolvement

nvol

nv

olve

ol

veme

eme

ment

nt iin

n

70% of cases. LV late-enhancement was identified by CE-CMR in 93% vs. 14% of controls

(p<0.001), with a regional distribution overlapping the histopathology findings.

Conclusions—MVP is an under-estimated cause of arrhythmic SCD, mostly in young adult

women. Fibrosis of papillary muscles and infero-basal LV wall, suggesting a myocardial stretch

by the prolapsing leaflet, is the structural hallmark and correlates with ventricular arrhythmias

origin. CE-CMR may help to identify this concealed substrate for risk stratification.

Key words: arrhythmia (mechanisms), mitral valve, sudden cardiac death, arrhythmia,

pathology, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, mitral valve prolapse

2

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

Introduction

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is the most common valve disease with an estimated prevalence of

2-3% in the general population1. Although MVP is generally regarded as a benign condition2,3,

the outcome is widely heterogeneous and complications such as mitral regurgitation, atrial

fibrillation, congestive heart failure, endocarditis and stroke are well known. Ventricular

arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (SCD) have been even reported4-7.

From a pathologic anatomy viewpoint, accumulation of proteoglycans (myxomatous

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

mitral valve) is the most common cause of MVP, accounting for leaflet thickening and

redundancy, chordal elongation, interchordal hoodings and anular dilatation8. While these valve

abnormalities well explain mitral regurgitation and mechanical complications duee tto

o en

enha

enhanced

hanc

ha

nced

nc

ed

extensibility, the pathogenesis of ventricular arrhythmias/SCD in MVP remains controversial.

The

The es

eestimated

tima

mate

ma

t d rate of SCD in MVP range

ranges

es fr

from 0.2% to 0.4% per

per year on the basis of

studies

pprospective

rosspective fo

ffollow-up

lllow-u

ow up stud

st

tud

udiies

ies4. Le

Left

ft ven

ventricular

enttricul

u ar (LV

(LV)

LV

V) dy

dysf

dysfunction

sfun

sf

fun

uncctio

ionn du

duee to sev

severe

ver

eree mi

mitr

mitral

tral

tr

al

regurgitation

egu

gurg

rgitatio

rg

on identifies

i en

id

e tifiees a patient

pattie

i nt

nt subgroup

suubg

b rooup

up at

at high

high

g risk

riisk off SCD

CD9. Ho

Howe

However,

w verr, lif

life-threatening

ifeif

e--threeat

ateenin

ng

veent

vent

ntri

ricu

ri

cula

larr ar

la

arrh

rhyt

rh

ythm

thm

hmia

iass oc

ia

occu

curr al

also

so iin

n MV

MVP

P pa

pati

tien

ti

entts with

en

wiith ttrivial

rivi

ri

vial

ial oorr ab

abse

sent

se

nt m

itra

it

rall re

ra

regu

gurg

rgit

rg

itat

it

atio

at

ionn10.

io

ventricular

arrhythmias

occur

patients

absent

mitral

regurgitation

Previous pathology studies of SCD mostly focused on the mitral valve or conduction system

abnormalities as cause of electrical instability8,11-17, while the demonstration of a myocardial

source of arrhythmias remained elusive18-20.

The aim of our report is to demonstrate that MVP is a significant cause of SCD and lifethreatening arrhythmias in young adults due to an underlying myocardial substrate, which is

detectable by contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance (CE-CMR) and may serve for risk

stratification and SCD prevention.

3

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

Material and Methods

Study populations

A) SCD victims with MVP

In the time interval 1982-December 2013, all the hearts of SCD victims 40 years old occurring in

the Veneto Region, North East Italy (geographic area 18,368 km2, overall population 4.857.210

according to the Italian Census Bureau 2011), were collected, pathologically investigated and

preserved. SCD is herein defined as witnessed sudden and unexpected death occurring within 1

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

hour of the onset of symptoms or death of an individual who had been seen in stable condition <24

hours before being found dead21,22. Demographic, clinical and pathologic data were recorded in the

electronic database of the Registry of Cardio-cerebro-vascular pathology which act

acts

ts as rreferral

efer

ef

erra

er

rall

ra

center for SCD of the North-East of Italy.

Charts

Char

Ch

arts

ar

ts were

weere

ere evaluated for age, sex, sympto

symptoms

toms

to

m and clinical history

history.

y. Al

A

Alll the hearts were

reexamined

carefully

standardized

eex

xamined car

ref

efullly

y aaccording

cccor

ordding

ng tto

o a st

sta

anddard

rdizzed pprotocol

rd

ro

otoco

coll21. SCD

co

SCD ca

case

cases

sess w

were

ere selected

sel

elec

eccte

tedd inn whom

who

hom

m

MVP

MV

P due to

om

myxomatous

yx

xom

mattou

ous valve

vaalv

l e disease

dise

seaasee was

se

was the

th

he only

onnly

y cardiac

caarddiacc abnormality

abn

norma

mali

ma

l ty

y ffound

ou

und at au

auto

autopsy.

topssy..

to

Myxomatous

M

My

yxo

xoma

oma

mato

tous

to

uss val

valve

alve

al

vee ddisease

isea

is

ease

ea

se is

is defined

defi

de

fine

fi

nedd as increased

ne

inc

ncre

reas

re

aseed le

as

leaf

leaflet

afle

af

lett le

le

leng

length

ngth

ng

th and

and redundancy,

red

edun

und

ndan

ancy

cy, with

wiith interchordal

int

nter

erch

er

chor

ch

orda

or

dall

da

hoodings and leaflet billowing toward the left atrium and chordae tendineae elongation8. In the

absence of extracardiac (cerebral, respiratory) or mechanical cardiovascular explanations, the

cause of death was considered cardiac arrhythmic.

Exclusion criteria were clinical and/or pathologic evidence of more than mild mitral

regurgitation. Hearts from 15 sex and age-matched patients (10 females, mean age 30 years, range

18-40), who died suddenly for extracardiac causes (8 cerebral and 7 respiratory), served as controls.

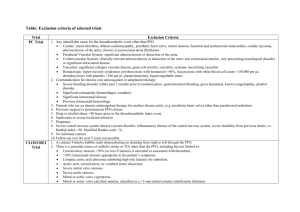

B) MVP patients with complex ventricular arrhythmias

The study included consecutive patients, referred to the Cardiology Clinic, from January 2010 to

4

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

December 2013, with complex ventricular arrhythmias detected on the basis of 12-lead 24-hour

Holter monitoring and echocardiographic diagnosis of MVP, defined as >5 mm thickening and

>2-mm displacement of one or both mitral leaflets into the left atrium as viewed in the LV

outflow tract orientation23. Twelve-lead ECG 24 hours Holter was requested due to the presence

of either arrhythmic symptoms or 12-lead ECG changes. Complex ventricular arrhythmias

consisted of ventricular fibrillation (VF) and ventricular tachycardia (VT), either non-sustained

or sustained24. Complex ventricular arrhythmias patients were further sub-divided into two

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

groups, i.e. those with 3 ventricular premature beats (VPB) run and those >3 VPB run.

The control group consisted of MVP patients with minor ventricular arrhythmias, i.e.

solated VPB, couplets and bigeminal VPB.

isolated

Exclusion criteria were significant mitral regurgitation, tricuspid dysplasia or

eguurg

rgit

itat

it

atio

at

ion,

io

n, car

ardi

ar

d omyopathies orr congenital he

di

ear

artt abnormalities, hem

mod

odynamic unstable

regurgitation,

cardiomyopathies

heart

hemodynamic

conditions

con

nd

and ccontraindication

oon

ntrraind

ndic

dic

icaatio

ionn to C

io

MR. T

MR

he study

yw

as app

ppro

pp

r ve

ro

vedd by tthe

he ins

he

sti

titu

tuti

tu

tion

ti

onal

on

al rreview

evie

ev

iew

ie

w

conditions

CMR.

The

was

approved

institutional

booar

ard,

d and aall

ll pa

atieentss gave

ga iinformed

nffor

o me

medd co

cons

n en

nt..

board,

patients

consent.

Prot

Pr

otoc

ot

ocol

oc

olss of iinvestigation.

ol

nves

nv

esti

es

tiga

ti

gati

ga

tion

ti

on.

on

Protocols

A) Pathologic anatomy study

Formalin-fixed hearts were restudied according to a protocol previously reported21. Leaflet

involvement (whether anterior, posterior or bileaflet) and the presence of endocardial fibrous

plaque (friction lesion) on the LV infero-basal wall were assessed. Multiple samples of the LV

and right ventricular free walls and septum, including the papillary muscles (PMs), were

obtained for histology. Additional samples were taken in the LV infero-basal free wall,

underneath the posterior mitral leaflet. Five μm-thick sections were stained with HematoxylinEosin, Weigert-van Gieson, Heidenhain trichrome and Alcian-PAS. Morphometric analysis was

5

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

performed using an Image-Pro Plus program (Version 4.0. Media Cybernetics, MD, USA) to

quantify the fibrous tissue percent area of LV myocardium on Heidenhain trichrome stained

sections at 25x magnification. Mean cardiomyocytes diameter was calculated on Haematoxylineosin stained sections at 400x magnification. Quantitative analysis was performed by two blind

expert pathologists (CB, SR) with an interobserver variability <5%.

B) Clinical study

All patients underwent cardiovascular evaluation including history, physical examination, 12Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

lead electrocardiogram (ECG), 2D-transthoracic echocardiography, 12-lead 24-hour Holter

monitoring and CE-CMR. Coronary angiography was performed in selected cases. The 12-lead

revi

re

viou

vi

ousl

ou

slyy

sl

ECG at rest and the 24-hour Holter monitoring were independently assessed as pre

previously

eported25 by two experienced observers (MDL and DC) who were blinded to patient data.

reported

NonNo

n-su

ns sttai

ainned VT was defined as 3 con

onnsec

secutive VPBs with a ra

ate > 100 bpm that lasted

Non-sustained

consecutive

rate

<

<30

300 seconds du

during

uri

rinng 224-hour

4-ho

4hour

ho

ur H

Holter

olte

ol

ter mo

te

mon

monitoring.

nitori

ring

ri

g. Su

Sustained

ustaine

nedd VT w

ne

was

as ddefined

efin

ef

ineed aass tachycardia

in

tach

ta

chyc

ch

ycarrdia

yc

dia

originating

orrig

igin

inatingg in thee ventricle

in

venttricle with

witth rate

ratte >100

>1

100 bbeats/minute

eats

ea

t /m

min

nutte an

aand

d la

lasting

astiing >

>30

30

0 seco

seconds

ondds orr re

requ

requiring

uiriing an

an

intervention

nte

terv

rven

enti

en

tion

ti

on ffor

or ttermination.

ermi

er

mina

mi

nati

na

tion

ti

on.

on

Cardiac magnetic resonance was performed on a 1.5-Tesla scanner (Magnetom Avanto,

Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). All patients underwent detailed CE-CMR

study protocol as previously described25. The presence and location of late gadolinium

enhancement (LGE) were independently assessed by two experienced observers (MPM and BG)

who were blinded to clinical data. To exclude artifact, LGE was deemed present only if visible in

two orthogonal views (long-axis and short-axis). LGE was identified using a signal intensity

threshold of >5SD above a remote reference region and quantified according to a previously

reported method.

6

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean value±standard deviation or median with 25 to 75 percentiles for

normally distributed and skewed variables, respectively. Normal distribution was assessed using

Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical differences between groups were evaluated by the chi-square test

or the Fisher exact test as appropriate. Paired and unpaired t test were used to compare normally

distributed continuous variables respectively obtained from the same patient and different

patients; Wilcoxon signed rank test (same patient) and Wilcoxon rank sum test (independent

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

samples) were used for skewed continuous variables.

A p value <0.05 was considered significant. The minimal detectable effect at a

significance

ignificance level of 5% and power at 80% is equal to 1 (with non parametric test)

t) ffor

or

quantitative variables (Cohen’ Effect); for binary data an odds ratio of at least 10 can be detected

iff the

complex

hee proportion

pro

ropo

port

po

rtionn of the characteristic test is equal

rt

al tto

o 10% in the no com

mpl x ventricular

mple

arrhythmias

arrh

ar

hythmias group

grou

oupp (Fisher’s

ou

(F

Fishe

ishe

her’

r s exact

exaact

ex

act test).Statistics

test

te

stt).

) Stattis

i tiics were

we analyzed

analy

naly

lyzzedd with

with SPSS

SPS

PSS version

vers

ve

rsio

rs

ionn 19

io

1 (SPSS

(SP

SPSS

SS Inc,

Inc

Chicago,

IL).

Ch

hiccag

a o, IL)

L).

L)

Results

A) SCD victims with MVP

Among 650 consecutive young SCDs recorded in the Veneto Region Registry , 43 cases (26

females, median age 32 years, range 19-40) with MVP due to myxomatous valve disease were

identified. They represent 7% of all SCD cases and 13% of women who died suddenly, being the

first structural cause in the latter group. Main clinical and pathologic data are reported in Table

1. SCD occurred mostly at rest or during sleep (N=35, 81%). Twenty (47%) had an in vivo

diagnosis of MVP, with auscultatory click in 18 (90%) and palpitations in 14 (70%). Nine (21%)

7

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

were under beta-blockers therapy due to non sustained ventricular arrhythmias. ECG was

available in 12 (28%), showing negative/isodiphasic T waves on inferior lead in 10/12 (83%)

(Figure 1A,B); all had right bundle branch block (RBBB) morphology (100%) ventricular

arrhythmias.

In SCD cases with MVP, valve leaflets were redundant, thick and elongated, with either

isolated posterior (N=13, 30%) or bileaflet (N=30, 70%) involvement (Figure 1C). The

involvement of the posterior leaflet was diffuse in 23 (53%) and confined to the medial scallop in

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

20 (47%). Endocardial fibrous plaques in the postero-lateral wall were found in 25 (58%).

Microscopic examination of the LV myocardium showed an increased endo-perimysial

and patchy replacement-type fibrosis at the level of PMs and adjacent free wall in

n aall

ll ((Figure

Figu

Fi

gure

gu

re

1D,E and Figure 2). Similar findings, with a subendocardial-midmural layer distribution, were

detected

infero-basal

leaflet,

deteect

cted

ed iin

n th

the in

nfe

fero-basal wall, underneath thee pposterior

o terior mitral valve le

os

leaf

a let, in 38 cases (88%).

The

Thee mean fibrous

fib

bro

ous tissue

tisssu

suee percent

perc

pe

rcen

rc

entt area

en

area in

in MVP

MV

VP SCD

D victims

vict

ctim

ct

imss was

im

wass 30.5%

30.5%

5% att thee level

level

evel of

of PMs

PMs and

and

33.1%

wall

myocardium

(vs.

and

controls,

p<0.001).

333.1

.1%

% in the

hee iinfero-basal

nffero-baasaal wa

alll m

yoca

yo

c rd

diu

ium

m (v

vs. 6.3% an

nd 66.4%

.4%

4% iin

n co

onttro

ols, p<

p<0.00

01).

1) In

n tthe

he

same

ame areas,

are

reas

as, the

as

the cardiomyocytes

card

ca

rdio

rd

iomy

io

myoc

ocyt

oc

ytes

tes showed

sho

howe

wed

ed increased

incr

in

crea

cr

ease

ea

sedd diameter

se

diam

di

amet

am

eter

et

er (19.2±6.0

(19.2±6

2±6.00 micron

mic

icro

ronn vs.

ro

vss 12.8±0.4,

12.8±0

8±0.4,

4

p<0.001) and dysmorphic and dysmetric nuclei.

B) MVP patients with complex ventricular arrhythmias

The baseline clinical and CMR findings are summarized in Table 2. Fourteen MVP patients with

or without minor ventricular arrhythmias (i.e. isolated VPB, couplets and bigeminal VPB) served

as controls.

Thirty MVP patients (22 female, median age 41) with complex ventricular arrhythmias,

i.e. 1 VF (N=2, who had also non-sustained VT) and VT (N=28) - either non-sustained (N=27)

or sustained (N=1)- were collected. VT of LV origin (RBBB morphology) was present in all,

8

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

with either inferior (43%) or superior (87%) axis. Among the 27 patients with non-sustained

VT, the mean length was 4 beats (ranging 3-11 beats). Complex ventricular arrhythmias occurred

at rest in 26/30 (87%). All patients had normal QTc (mean 423, range 409-440). Exercise stress

test, performed in 20,was negative for effort-induced ventricular arrhythmias.

Bileaflet MVP was present in 21 (70%) patients with complex ventricular arrhythmias vs.

5 (36%) controls (p=0.031).

On post-contrast sequences, LV-LGE was identified in 28 (93%) vs. 2 (14%) (p<0.001).

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

By dividing the MVP population with complex ventricular arrhythmias into two sub-groups, 20

patients had 3 VPB run and 10 patients >3 VPB run (p>0.05). In MVP patients with complex

comparing

those

ventricular arrhythmias, no difference was found in terms of LV-LGE when comp

mp

par

arin

ingg th

in

thos

osee

os

with 3 VPB run and those >3 VPB run (p>0.05).

The

mid-apical

The LGE

L E was

LG

was localized on the PMs in 255 ppatients

a ients (83%), with a mi

at

m

d-apical distribution in

segment,

underneath

1166 and/or

and/or basall adjacent

adjjace

ad

cent

ntt free

fre

reee wall

w ll in

wa

in 24 cases;

casees;; andd on

on the

the LV

LV infero-basal

in

nfe

f ro-b

-bas

bas

asaal seg

egm

eg

ment

ment

nt, un

unde

dern

de

rnea

rn

eath

ea

th

the

3A-D).

focal

LGE

region,

he posterior

posterio

po

or leaflet,

l affleet, inn 22

le

22 (73%)

(73

73%)

73

%) (Figure

(Fi

Figu

uree 3A

A-D

D). A fo

ocaal eendocardial

ndo

doca

do

caardia

rdiaal LG

L

GE in the ssame

am re

ame

egionn,

featuring

fibrous

plaque,

found

patients

feat

fe

atur

at

urin

rin

ingg a fi

fibr

brou

br

ouss pl

plaq

aque

aq

ue,

e was

waas fo

foun

und

nd in 112

2 pa

pati

tien

ti

ents

en

ts ((40%).

40%)

40

%).

%)

The median LV LGE % was 1.2 in MVP with complex ventricular arrhythmias vs. 0 in

MVP without (p<0.01).

Two MVP patients experienced aborted SCD due to VF, despite beta-blocker therapy due

to previous sustained VT. Detailed invasive and non-invasive evaluation ruled out cardiac

causes other than MVP. Both had RBBB pattern ventricular arrhythmias with superior axis and T

waves abnormalities on inferior leads. CE-CMR, performed 6 and 10 months before aborted

SCD, revealed LV LGE of PMs and infero-basal wall (Figure 3 E,F). Both patients received an

implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD).

9

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

One patient had pre-syncopal episodes despite bisoprolol therapy. She underwent

electrophysiological study with induction of sustained VT with the same RBBB morphology of

VPBs (Figure 4A-C). The CE-CMR showed a non-ischemic LGE pattern in the LV infero-basal

wall (Figure 4D). She also underwent ICD implantation.

Of the three patients with ICD (mean follow-up 10 months), two had non sustained-VT:

one patient with spontaneous interruption and the other requiring anti-tachycardia pacing.

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

Discussion

MVP is an under-recognized cause of SCD in young adults, accounting for 7% of total fatal

with

events and 13% of female victims in our large Cardiac Registry experience. The ppatient

atie

at

ient

ie

nt w

ithh

it

MVP and ventricular arrhythmias at risk of SCD is usually a young adult woman, with a midsystolic

auscultation,

involvement

ysttol

olic

ic cclick

lick

li

ck at au

ausc

s ultation, bileaflet involvem

men

entt of the mitral valve, T wave abnormalities on

inferior

RBBB-type

polymorphic

arrhythmias

ECG.

Clear-cut

nfeerior leads, RB

RBBB

BB

B-typ

ypee or po

yp

poly

lym

ly

morp

morp

rphhic vventricular

enntriccullar ar

arrh

rhyt

rh

ythm

yt

hmia

hm

i s on E

ia

CG. Cl

Clea

earea

r cu

rcutt ev

eevidence

iden

id

encee

en

electrical

instability

herein

provided

first

consists

off a ssubstrate

ubstraate off el

lectrriccal ins

nstaabi

ns

b liity inn MV

MVP

P iiss he

ereeinn pr

prov

vid

ded

d ffor

or tthe

or

h fi

he

irstt ttime

im

me an

andd co

onssistss ooff

myocardial

LV

wall,

underneath

myoc

my

ocar

oc

ardi

ar

dial

di

al scarring

sca

carr

rrin

rr

ingg targeting

in

targ

ta

rget

rg

etin

et

ingg the

in

the PMs

PMs and

and the

the infero-basal

infe

in

fero

fe

ro-bas

bas

asal

al L

V fr

free

ee wal

alll, und

al

nder

nd

erne

er

neat

ne

athh th

at

thee

posterior leaflet, well in keeping with the site of origin of RBBB-type ventricular arrhythmias.

The LV myocardial fibrosis observed at histology in SCD victims was then confirmed in the

clinical arm of the study, with evidence of LGE at CE-CMR in arrhythmic MVP patients, thus

pointing to a promising role of this non invasive technique for risk stratification beyond

traditional prognostic markers.

MVP: an underappreciated cause of SCD

The absence of uniform diagnostic criteria of MVP in the general and forensic pathology practice

and the frequent consideration of this valve disease as an uncertain cause of SCD are major

10

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

obstacles to provide data on the real burden of MVP based upon a metanalysis of published

studies21. With these shortcomings, the prevalence of MVP in pathology series of SCD in the

young ranges from 0 to 24%20,22,26,27. By adopting strict criteria for definition of myxomatous

mitral valve, in the Veneto Region SCD Registry MVP accounted for 7% of all cases in young

adults (<40 years) and 13% among women, representing the first structural cause in the latter

group. The diagnosis can be easily established at macroscopic examination and then confirmed

by routine histology, but it might be overlooked by superficial inspection, leading to discharge

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

the heart as normal. Our data are likely to change the current thinking about MVP as a benign

condition and point to the need to draw the attention of forensic pathologists to an entity that has

been largely underestimated so far.

Ventricular arrhythmias in MVP

nM

VP sseries

erie

er

ies wi

ie

with

th prolonged ECG recording, a vvariable

ar

ariable

prevalence off vventricular

entricular arrhythmias

In

MVP

ha been reported,

has

reporte

ted,

te

d, reflecting

ref

efllect

ef

lect

ctin

ingg the

in

the different

diff

di

fferren

ff

nt MVP

MV definition,

deefi

finiti

tion

ti

on, the

on

the population

popu

po

pula

pu

lattio

la

ionn studied

stud

udie

ud

iedd and

ie

an the

th

5,9,10,28-35

5,9,10,2

,28

28-3

-35

-3

co

omp

mplexity

y ooff ve

enttricu

ulaar ar

rrh

rhyt

ythm

yt

mia

ias co

onsid

ideered5,9

id

. In pparticular,

arrtiicu

ula

l r, tthe

hee cl

clinical

lin

i icaal eevidence

vide

deencee ooff

complexity

ventricular

arrhythmias

considered

hemo

he

mody

mo

dyna

nami

na

mica

mi

call

ca

lly im

ll

impo

port

po

rtan

rt

antt re

an

regu

gurg

rgit

rg

itat

it

atio

at

ionn gr

io

grea

eatl

ea

tly iimpacts

tl

mpac

mp

acts

ac

ts oon

n th

thee oc

occu

curr

rren

rr

ence

en

ce ooff vent

ve

ent

ntri

ricu

ri

cula

larr

la

hemodynamically

important

regurgitation

greatly

occurrence

ventricular

arrhythmias. However, the detection of MVP in survivors of life-threatening arrhythmias

suggests that a true association between hemodynamically uncomplicated MVP and arrhythmic

SCD may exist9. Thus, we decided to focus on "pure" MVP, excluding MVP associated with

valve incompetence and LV remodelling, not to defile the message by over-reporting ventricular

arrhythmias. Early electrophysiological studies demonstrated that the most common site of origin

of VPB is the infero-basal portion of the LV36. In the recent study of malignant MVP by Sriram

et al37, frequent VPBs originated from the outflow tract and PMs. Moreover, electrophysiology

mapped the site of origin to the PMs, the LV outflow tract and the mitral annulus, as to suggest

11

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

that VPBs arising close to the prolapsing leaflet and adjacent structures are the arrhythmic

triggers.

From a pathophysiologic perspective, the mechanism of ventricular arrhythmias in MVP

patients with trivial or absent mitral regurgitation remains speculative9,38. MVP-related factors

have been first advocated, such as the excessive traction on the PMs by the prolapsing leaflets39;

the mechanical stimulation of the endocardium by the elongated chordae, with after

depolarization-induced triggered activity; the diastolic depolarisation of muscle fibres in

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

redundant leaflets with triggered repetitive automaticity40; and the endocardial friction lesions

with extension into the myocardium41. Moreover, the coexistence of extravalvular diseases has

been suggested, including autonomic nervous system dysfunction42, conduction ssystem

yste

ys

tem

te

m

abnormalities13, fibromuscular dysplasia of small coronary arteries19 and occult

10,43

1

10

43

card

dio

iomy

myop

my

opat

op

athiees10,

at

.

cardiomyopathies

T

The

hee myocardial

al ssubstrate

ub

bstra

rate

ra

te ooff el

elec

electrical

ectr

ec

tric

tr

icall ins

ic

instability

sta

abiliity

y in

n MV

MVP

P

Previous

pathology

studies

MVP

patients

mostly

Pr

rev

evio

i us pat

io

attho

h lo

ogy

y stu

udies iin

nM

VP

P pa

atieentss ddying

y ngg ssuddenly

yi

udddeenlyy mo

mos

stly

y ffocused

occussed

d onn mitral

mittraal valve

vaalvve

structural

tru

ruct

ctur

ct

ural

ral aalterations,

lter

lt

erat

er

atio

at

ions

io

ns, su

ns

ssuggesting

ugg

gges

gg

esti

es

ting

ti

ng a ro

role

le ffor

or aannular

nnul

nn

ular

lar ccircumference,

ircu

ir

cumf

mfer

mf

eren

er

ence

en

ce, le

ce

leaf

leaflets

afle

af

lets

le

ts llength

engt

en

gthh an

gt

andd th

thic

thickness

ickn

ic

knes

kn

esss

es

and presence and extent of endocardial plaques8,14-17. Surprisingly, no investigation did

systematically address the LV myocardium to search for the substrate of electrical instability,

except for few anecdotic cases11,13,14,44,45. For the first time, we extended the histopathology

investigation beyond the valve in all SCD cases and provided convincing evidence of fibrosis in

the LV myocardium, which is closely linked to the mitral valve, i.e. the PMs with adjacent free

wall and the infero-basal wall. The LV myocardial scarring is qualitatively different from that

observed in ischemic heart disease, where it is usually compact and confluent, being instead

patchy and interspersed within surviving, hypertrophic cardiomyocytes. Noteworthy, previous

12

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

pathology studies addressed the so-called “idiopathic myocardial fibrosis” in SCD victims46. By

definition this entity is not associated with other structural heart diseases and remains without an

explanation. However, the LV fibrosis described in our MVP cases differ in terms of type (i.e.

scarring) and location (i.e. LV papillary muscles and basal postero-lateral wall).

Furthermore, we herein demonstrate that CE-CMR can detect LV-LGE in MVP patients

with complex ventricular arrhythmias, closely overlapping the histopathologic features observed

in SCD victims. At the level of PMs, two LGE sites have been found, i.e. the mid-apical portion

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

and the base/adjacent LV wall. Although PMs LGE has been reported by Han et al24 in MVP

patients with a history of arrhythmias, most of these patients had moderate to severe mitral

regurgitation.

egurgitation. While confirming

f

these data in purely arrhythmic MVP patients wi

without

ith

thou

outt

ou

hemodynamic impairment, we first provide convincing evidence of LGE in the infero-basal LV

wall.

wall

l. The

The arrhythmogenic

arrh

ar

rhythm

rh

hmogenic role of the LV myocardial

hm

myocaard

rdia

ial scarring is suppor

ia

supported

rte

tedd by the morphology of

arrhythmias

arrh

ar

hythmias andd byy eelectrophysiological

lect

le

ctro

ct

roph

ro

phys

ph

ysiiolo

ys

iolo

logi

giccall studies

gi

sttud

udiees inn MVP

MVP indicating

ind

ndic

icat

ic

atin

i g that

that the

thhe most

most

ost common

comm

co

mmon

mm

on site

sit

itee of

o

36,37

6,37

VPB

LV

wall

VP

B origin is

is the

th

he infero-basal

infeero

ro-bassal L

V wa

w

lll36

.

Most

Mo

st ooff CE

-CMR

CMR sstudies

tudi

tu

dies

di

es ffor

or aarrhythmic

rrhy

rr

hyth

thmi

th

micc ri

mi

risk

sk sstratification

trat

tr

atif

at

ific

if

icat

ic

atio

at

ionn ar

io

aree co

comi

ming

mi

ng ffrom

rom

ro

m ei

eith

ther

th

er

CE-CMR

coming

either

ischemic heart disease or cardiomyopathies, with the notion the larger the LGE burden the worse

the prognosis. Our quantitative data suggest that the volume of LV scarred tissue in MVP is

relatively small but still associated with SCD.. We should recognize that MVP differs from other

non-valvular diseases in terms of LGE distribution (“stretched areas”) and amount. Furthermore,

the mechanical stretch by the prolapsing leaflet and elongated chordae could act as a trigger of

electrical instability. Further studies with higher number of MVP patients are needed to confirm

these preliminary data of LV LGE.

Since the early descriptions, abnormal LV contraction pattern and ECG abnormalities

13

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

suggested that MVP has a significant myocardial involvement47-51. The hypothesis that the socalled “MVP syndrome” is a cardiomyopathy, where regional hypercontractility acts as the

primum movens of mitral valve geometry disruption, with abnormal tension on the chordae and

leaflets and secondary increase in myxomatous tissue and leaflet thickening, has been even

advanced50,51. Our pathology and CE-CMR data support the theory that LV abnormalities are

rather the consequence of MVP, due to a systolic mechanical stretch of the myocardium closely

linked to the valve, i.e. PMs and infero-basal wall, by the prolapsing leaflets and elongated

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

chordae, accounting for a localized hyper-contractility, with myocyte hypertrophy and injury

leading eventually to fibrous tissue repair. The increased cardiomyocyte diameter, in the same

areas showing replacement-type fibrosis, is in keeping with this theory.

Considering that performance of CE-CMR in all MVP patients would be an expensive

prop

pos

osit

itio

it

ion,

io

n, some

som

me clinical

c inical markers that could target

cl

targ

rget

rg

et a high-risk subgroup

subgrouup destined for screening

proposition,

by CE-CMR

by

CE-CMR are

arre needed.

need

eded

ed

ed.. ECG

ed

ECG depolarization

depol

epol

olar

arizzattio

ar

ionn abnormalities

abno

norrmal

alit

al

itie

it

iess on infero-lateral

ie

inffer

eroo latteraal leads,

olead

le

ads,

ad

s, complex

com

ompl

plex

pl

ex

ve

ent

ntri

r cular ar

ri

arrh

r ythmiaas ((

3 VPB

VPB

P run)

run

u ) with

with

h RBBB

RBBB

B morphology

morpphoology

mo

logy on

on 12-lead

122-lleaad ECG

EC Holter

Hollter

Ho

ventricular

arrhythmias

moni

mo

nito

ni

tori

to

ring

ri

ng and

and a hhistory

isto

is

tory

to

ry ooff pr

pre

e-sy

sync

ncop

nc

opee, syncope

op

sync

yn

ncop

opee an

andd ab

abor

orte

or

tedd SC

te

SCD

D se

seem

em tto

o re

repr

pres

pr

esen

es

entt an

en

monitoring

pre-syncope,

aborted

represent

indication for CE-CMR.

Finally, we recognize that our data support an association between anatomic substrate and

risk, in an entity that is underappreciated as a cause of SCD and also has a low enough incidence

that any marker of increased risk might be of significant value to the clinician.

Beta-blockers are commonly used to treat arrhythmias in MVP patients. The fact that

21% of young adult SCD victims and two living patients had aborted SCD despite beta-blocker

therapy is disappointing but not surprising10. Prospective multicenter studies are warranted to

support the role of CE-CMR and electrovoltage mapping for risk stratification and to assess the

14

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

efficacy of antiarrhythmic therapy and targeted catheter ablation in selected cases.

Limitations of the study

While acknowledging the small number of MVP patients without complex ventricular

arrhythmias, we should recognize that it is difficult to collect “pure” MVP patients without either

valve incompetence or ventricular arrhythmias both clinically and at postmortem. Prospective

multicenter studies enrolling a higher number of MVP, with and without complex ventricular

arrhythmias, are warranted to evaluate the exact prevalence of LGE in the overall MVP

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

population.

Genetic data are not available in our SCD population. Noteworthy, in our series of SCD

(47%)

victims there was macroscopic evidence of myxomatous mitral valve and nearly half

hal

alff (4

(47%

7%)) ha

7%

had

a previous in vivo diagnosis of MVP, with a cardiological check-up ruling out channelopathies.

Moreover,

ECG,

revision

More

reov

re

over

ov

er,, the

er

the EC

CG,

G which was available for revi

visi

vi

sioon in 28%, did not sshow

si

how any evidence of

ho

long/short

MVP

ong

g/short QT or Brugada

Bru

uga

gada

da syndromes.

syn

yndr

drom

dr

omes

om

e . Of

Of the

the rremaining

emaain

nin

ng 31 M

VP ccases,

ases

as

es,, 225

es

5 ((80%)

80%)

80

%) hhad

a ffirstad

irst

st-st

degree

de

egr

gree

e family

famil

illy members

meemberrs referred

mem

refeerred

ed for

or cardiological

caarddiolog

ogiical screening,

og

sccreeening

ng, without

ng

wi ho

witho

hout

utt any

anny evidence

evi

vide

vi

deence of

channelopathies,

MVP

cases

(16%).

chan

ch

anne

an

nelo

ne

lopa

lo

path

pa

thie

th

iess, bbut

ie

utt M

VP iin

n 4 ca

case

sess (1

se

(16%

6%)).

6%

Although we are strong supporters of the relevance of molecular autopsy in the study of

SCD21,22, we follow the indication by the HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement52.

According to these guidelines, an arrhythmia syndrome-focused postmortem genetic testing can

be useful for all sudden unexplained death syndrome victims as Class IIa indication; furthermore,

evaluation of first-degree blood relatives with resting ECG with high right ventricular leads,

exercise stress testing, and echocardiography is recommended as Class I.

Conclusions

This study suggests that MVP is a significant cause of SCD in young adults and is the leading

15

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

one in women. Arrhythmic MVP patients are mostly female with ventricular arrhythmias of LV

origin and frequent repolarization abnormalities on inferior leads. The hallmark of arrhythmic

MVP is fibrosis of PMs and infero-basal LV free wall, which well correlates with arrhythmia

morphology, pointing to a myocardial stretch by the prolapsing leaflets and elongated chordae.

CE-CMR allows the identification of this arrhythmic substrate and is a promising non-invasive

tool for risk stratification and SCD prevention.

Funding Sources: This work was supported by the Registry of Cardio- Cerebro-Vascular

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

Pathology, Veneto Region, Venice, Italy; Target Project “Sudden cardiac death in women”,

Regional Health System, Venice, Italy.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None.

References:

Re

efe

ferrences

re es

es::

11.. D

Delling

elling FN, V

Vasan

assan R

RS.

S. E

Epidemiology

pidemi

pid

mioolog

ol gy andd ppathophysiology

athopphys

ysiiolo

ys

ogy

y off m

mitral

itrall vvalve

alvve prola

prolapse:

laps

la

pse: ne

ps

new

ew

insights

molecular

basis.

Circulation.

nsiigh

g ts into disease

d seeasse progression,

di

progresssio

ion, genetics,

io

geene

neticcs, aand

ndd mo

oleecu

ula

larr ba

bas

sis. Ci

irculaatiionn. 22014;129:2158014;1229:21

211582170.

21

170

70.

22. Freed LA,

LA Levy D,

D Levine RA,

RA Larson MG,

MG Evans JC,

JC Fuller DL,

DL Lehman B,

B Benjamin EJ.

EJ

Prevalence and clinical outcome of mitral-valve prolapse. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1–7.

3. Freed LA, Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Larson MG, Evans JC, Fuller DL, Lehman B, Levine RA.

Mitral valve prolapse in the general population: the benign nature of echocardiographic features

in the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1298-1304.

4. Nishimura RA, McGoon MD, Shub C, Miller FA Jr, Ilstrup DM, Tajik AJ.

Echocardiographically documented mitral-valve prolapse. Long-term follow-up of 237 patients.

N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1305-1309.

5. Düren DR, Becker AE, Dunning AJ. Long-term follow-up of idiopathic mitral valve prolapse

in 300 patients: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;11:42-47.

6. Marks AR, Choong CY, Sanfilippo AJ, Ferré M, Weyman AE. Identification of high-risk and

low-risk subgroups of patients with mitral-valve prolapse. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1031-1036.

7. Avierinos JF, Gersh BJ, Melton LJ III, Bailey KR, Shub C, Nishimura RA, Tajik AJ,

16

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

Enriquez-Sarano M. Natural history of asymptomatic mitral valve prolapse in the community.

Circulation. 2002;106:1355-1361.

8. Davies MJ, Moore BP, Braimbridge MV. The floppy mitral valve. Study of incidence,

pathology, and complications in surgical, necropsy, and forensic material. Br Heart J.

1978;40:468-481.

9. Kligfield P, Levy D, Devereux RB, Savage DD. Arrhythmias and sudden death in mitral valve

prolapse. Am Heart J. 1987;113:1298-1307.

10. Vohra J, Sathe S, Warren R, Tatoulis J, Hunt D. Malignant ventricular arrhythmias in

patients with mitral valve prolapse and mild mitral regurgitation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol.

1993;16:387-393.

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

11. Jeresaty RM. The syndrome associated with mid-systolic click and-or late systolic murmur.

Analysis of 32 cases. Chest. 1971;59:643-647.

12. Shappell SD, Marshall CE, Brown RE, Bruce TA. Sudden death and the familiall occurrence

1973;48:1128-1134.

of mid-systolic click, late systolic murmur syndrome. Circulation. 1973;48:1128-11

1134

34..

34

13. Bharati S, Granston AS, Liebson PR, Loeb HS, Rosen KM, Lev M. The conduction system

in

n mitral valve prolapse syndrome with sudden death. Am Heart J. 1981;101:667-670.

14.

Chesler

E,, King RA, Edwards JE. The myxoma

myxomatous

valve

14

4. C

hesler E

matous mitral va

ma

alv

lve and sudden death.

Circulation.

C

irc

rculation. 1983;67:632-639.

rc

198

983;

98

3;677:6

:632

32-6

32

-639

-6

39

9.

15.

WA,

Bosman

CK,

Chesler

Barlow

JB,

Edwards

JE.

Sudden

15

5. Pocock

Po

W

A,, B

osma

man CK

ma

K, Ch

C

esle

es

l r E,

E, Ba

arllow JB

B, Ed

Edwa

ard

rds JE

E. Su

udd

den ddeath

eath

ea

t inn pprimary

rim

mary

prolapse.

1984;107:378-382.

mitral

al vvalve

alvve

al

ve pro

ola

laps

pse.

se Am

m Heart

Hea

art J.

J. 1984;

4;10

4;

107:

10

7:37

7:

37837

8 382.

38

82

16. Dollar AL, Roberts WC. Morphologic comparison of patients with mitral valve prolapse who

died suddenly with patients who died from severe valvular dysfunction or other conditions. J Am

Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:921-931.

17. Farb A, Tang AL, Atkinson JB, McCarthy WF, Virmani R. Comparison of cardiac findings

in patients with mitral valve prolapse who die suddenly to those who have congestive heart

failure from mitral regurgitation and to those with fatal noncardiac conditions. Am J Cardiol.

1992 ;70:234-239.

18. Morales AR, Romanelli R, Boucek RJ, Tate LG, Alvarez RT, Davis JT. Myxoid heart

disease: an assessment of extravalvular cardiac pathology in severe mitral valve prolapse. Hum

Pathol. 1992;23:129-137.

19. Burke AP, Farb A, Tang A, Smialek J, Virmani R. Fibromuscular dysplasia of small

coronary arteries and fibrosis in the basilar ventricular septum in mitral valve prolapse. Am Heart

J.1997;134:282-291.

17

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

20. Corrado D, Basso C, Nava A, Rossi L, Thiene G. Sudden death in young people with

apparently isolated mitral valve prolapse. G Ital Cardiol. 1997;27:1097-1105.

21. Basso C, Burke M, Fornes P, Gallagher PJ, de Gouveia RH, Sheppard M, Thiene G, van der

Wal A; Guidelines for autopsy investigation of sudden cardiac death. Association for European

Cardiovascular Pathology.Virchows Arch. 2008;452:11-18.

22. Basso C, Calabrese F, Corrado D, Thiene G. Postmortem diagnosis in sudden cardiac death

victims: macroscopic, microscopic and molecular findings. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;50:290-300.

23. Levine RA, Stathogiannis E, Newell JB, Harrigan P, Weyman AE. Reconsideration of

echocardiographic standards for mitral valve prolapse: lack of association between leaflet

displacement isolated to the apical four chamber view and independent echocardiographic

evidence of abnormality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;11:1010-1019.

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

24. Han Y, Peters DC, Salton CJ, Bzymek D, Nezafat R, Goddu B, Kissinger KV, Zimetbaum

PJ, Manning WJ, Yeon SB. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance characterization of mitral valve

prolapse. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;1:294

2008;1:294-303.

303.

25. Perazzolo Marra M, De Lazzari M, Zorzi A, Migliore F, Zilio F, Calore C, Vettor

Vet

etto

et

torr G, Tona

to

Ton

onaa F,

Tarantini G, Cacciavillani L, Corbetti F, Giorgi B, Miotto D, Thiene G, Basso C, Iliceto S,

Corrado D. Impact of the presence and amount of myocardial fibrosis by cardiac magnetic

resonance

esoona

nanc

ncee on arrhythmic

nc

arrrhy

hythmic outcome and sudden cardiac

caard

rdia

i c death in non ischemic

ische

hemi

he

m c dilated

cardiomyopathy.

caard

rdiiomyopat

io

athy. Heart Rhythm.

at

Rhyt

y hm. 2014;11:856-863.

2014;11:856-863

3.

26.

Kelly

KL,

Titus

Sudden

with

apparently

normal

heart.

2 . Chugh SS, K

26

ellly KL

K

L, Ti

itu

tus JL. Sudd

dden ccardiac

arrdiaac ddeath

eath

th w

ithh ap

ppaarenttly

y no

orm

mal he

hea

ar

art.

Circulation.

Circ

Ci

rcul

rc

u ation.. 22000;102:649-654.

00

00;

0;1022:6649-66544.

4.

27.

27 Topaz

Topa

To

paz O,

pa

O, Edwards

Edw

dwar

ards

ar

ds JE.

JE. Pathologic

Pat

atho

holo

ho

logi

lo

gicc features

gi

feat

fe

atur

at

ures

res of

of sudden

sudde

ud

dde

denn death

deat

de

athh in children,

at

chi

hild

ldre

ld

renn, adolescents,

re

ado

dole

lesc

le

scen

sc

ents

en

ts, and

ts

and

young adults. Chest. 1985;87:476-482.

28. Campbell RW, Godman MG, Fiddler GI, Marquis RM, Julian DG. Ventricular arrhythmias

in syndrome of balloon deformity of mitral valve. Definition of possible high risk group. Br

Heart J. 1976;38:1053-1057.

29. De Maria AN, Amsterdam EA, Vismara LA, Neumann A, Mason DT. Arrhythmias in the

mitral valve prolapse syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1976;84:656-660.

30. Winkle RA, Lopes MG, Popp RL, Hancock EW. Life-threatening arrhythmias in the mitral

valve prolapse syndrome. Am J Med. 1976;60:961-967.

31. Levy S. Arrhythmias in the mitral valve prolapse syndrome: clinical significance and

management. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1992;15:1080-1088.

32. Morady F, Shen E, Bhandari A, Schwartz A, Scheinman MM. Programmed ventricular

stimulation in mitral valve prolapse: analysis of 36 patients. Am J Cardiol. 1984;53:135-138.

18

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

33. Sanfilippo AJ, Abdollah H, Burggraf GW. Quantitation and significance of systolic mitral

leaflet displacement in mitral valve prolapse Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:1349-1355.

34. Kulan K, Komsuo÷lu B, Tuncer C, Kulan C. Significance of QT dispersion on ventricular

arrhythmias in mitral valve prolapse. Int J Cardiol. 1996;54:251-257.

35. Devereux RB, Kramer-Fox R, Shear MK, Kligfield P, Pini R, Savage DD. Diagnosis and

classification of severity of mitral valve prolapse: methodologic, biologic, and prognostic

considerations. Am Heart J. 1987;113:1265-1280.

36. Lichstein E. Site of origin of ventricular premature beats in patients with mitral valve

prolapse. Am Heart J. 1980;100:450-457.

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

37. Sriram CS, Syed FF, Ferguson ME, Johnson JN, Enriquez-Sarano M, Cetta F, Cannon BC,

Asirvatham SJ, Ackerman MJ. Malignant bileaflet mitral valve prolapse syndrome in patients

with otherwise idiopathic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:222-230.

Kramer-Fox

Natural

38. Zuppiroli A, Rinaldi M, Kramer

Fox R, Favilli S, Roman MJ, Devereux RB. Nat

tur

u al history

of mitral valve prolapse. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:1028-1032.

39. Cobbs BW Jr, King SB 3rd. Ventricular buckling: a ffactor in the abnormal ventriculogram

and peculiar hemodynamics associated with mitral valve prolapse. Am Heart J. 1977;93:741758..

440.

0. Salazar AE,

AE

E, Edwards

Edwa

Ed

ward

wa

rdss JE.

rd

JE. Friction

Fric

Fr

icti

ic

tioon lesions

ti

lessionns of

of ventricular

veentricu

cula

cu

larr endocardium.

la

end

ndoc

o ar

ardi

dium

di

um. Relation

um

Reela

lati

tion

ti

on to

to chordae

chorrda

ch

daee

tendineae

mitral

valve.

Arch

Pathol.

enddineae of mitra

r l va

ra

alv

lve. Ar

rch

h Pathol

l. 11970;90:364-376.

9700;990:364

4-376

76..

76

Barlow

Bosman

leaflet

mitral

valve.

41. Ba

Barl

rlow

rl

ow JB, B

ossma

mann CK.

C . Aneurysmal

CK

Aneu

An

eurysm

eu

mal protrusion

pro

rotr

trus

tr

ussion

ion off tthe

he pposterior

osteri

rioor

ri

or le

eaf

afle

lett off tthe

le

he m

itra

rall valv

ra

va

alv

lvee.

Heart

An aauscultatory-electrocardiographic

usscult

uscu

ltat

lt

ator

at

ory-el

or

elec

el

ectr

ec

troc

tr

ocar

oc

ardi

ar

diog

di

ogra

og

raph

ra

phic

ph

ic ssyndrome.

ynndr

yndr

drom

omee. Am

om

Am H

eart

rtt JJ.. 11966;71:166-178.

966;

96

6;71

6;

71:1

71

:166

:1

66-178

178

78.

42. Boudoulas H, Kolibash AJ, Baker P, King BD, Wooley CF. Mitral valve prolapse and the

mitral valve prolapse syndrome: a diagnostic classification and pathogenesis of symptoms. Am

Heart J. 1989;118:796-818.

43. Mason JW, Koch FH, Billingham ME, Winkle RA. Cardiac biopsy evidence for a

cardiomyopathy associated with symptomatic mitral valve prolapse. Am J Cardiol. 1978;42:557562.

44. Jeresaty RM. Sudden death in the mitral valve prolapse-click syndrome. Am J Cardiol.

1976;37:317-318.

45. Wilde AA, Düren DR, Hauer RN, deBakker JM, Bakker PF, Becker AE, Janse MJ. Mitral

valve prolapse and ventricular arrhythmias: observations in a patient with a 20-year history. J

Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1997;8:307-316.

46. John BT, Tamarappoo BK, Titus JL, Edwards WD, Shen WK, Chugh SS. Global remodeling

19

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

of the ventricular interstitium in idiopathic myocardial fibrosis and sudden cardiac death. Heart

Rhythm. 2004;1:141-149.

47. Hancock EW, Cohn K. The syndrome associated with midsystolic click and late systolic

murmur. Am J Med. 1966;41:183-196.

48. Scampardonis G, Yang SS, Maranhão V, Goldberg H, Gooch AS. Left ventricular

abnormalities in prolapsed mitral leaflet syndrome. Review of eighty-seven cases. Circulation.

1973;48:287-297.

49. Rizzon P, Biasco G, Brindicci G, Mauro F. Familial syndrome of midsystolic click and late

systolic murmur. Br Heart J. 1973;35:245-259.

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

50. Gulotta SJ, Gulco L, Padmanabhan V, Miller S. The syndrome of systolic click, murmur,

and mitral valve prolapse--a cardiomyopathy? Circulation. 1974;49:717-728.

51. Crawford MH, O'Rourke RA. Mitral valve prolapse: a cardiomyopathic state? Prog

1984;27:133-139.

Cardiovasc Dis. 1984;27:133

139.

52. Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M, Cho Y, Behr ER, Berul C, Blom N, Brugada J,

J, Chiang

Chia

Ch

iang

ia

ng CE,

CE,

Huikuri H, Kannankeril P, Krahn A, Leenhardt A, Moss A, Schwartz PJ, Shimizu W, Tomaselli

G, Tracy C. Executive summary: HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the

diagnosis

management

inherited

arrhythmia

diag

gno

nosi

siss an

si

andd ma

anagement

na

of patients with inher

erit

er

ited

it

e primary arrhythmi

miaa syndromes. Heart

mi

Rhythm.

2013;10:e85-108.

Rh

hyt

ythhm. 201

0113;10:e85-108.

20

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

Table 1. Clinical and pathologic features of 43 patients who died suddenly with MVP due to

myxomatous degeneration.

Variables

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

Age, years median (range)

Female, n (%)

Athletes, n (%)

Marfan stigmata, n (%)

Pectus excavatum, n (%)

Pregnancy, n (%)

Circumstances of SCD, n (%)

- on emotion/effort

- at rest

- during sleep

12 lead ECG available, n (%)

nverted/biphasic T wave D2, D3, aVF n (%)

Inverted/biphasic

VAs, n (%)

VAs morphology, n (%)

- RBBB

- LBBB

Be

Beta-blocker

eta

ta-b

-blo

-b

lock

lo

cker

ck

er the

therapy,

era

rappy, n (%)

G

Gross

rooss featur

features

res

H

eart weight (g)

), m

eaan ±

SD

D*

Heart

(g),

mean

±SD*

LV w

all thickness

thicckn

k esss (mm)

m), me

ean

n±SD

D

wall

(mm),

mean±SD

VS

S thickness

thi

hick

ckne

ck

nesss (mm),

ne

(mm

mm),

) m

),

eaan SD

ean±

D

mean±SD

Pate

Pa

Patent

tent

te

nt foramen

for

oram

amen

am

en oovale,

vale

va

le, n (%

le

(%)*

)*

O

Ovall ffossa aneurysm, n (%)

Posterior MVP, n (%)

Bileaflet MVP, n (%)

Endocardial fibrous plaque, n (%)

Histology features

LV scar

- papillary muscles, n (%)

-infero-basal wall, n (%)

Fibrous tissue /myocardium (% area)

- papillary muscles, mean ± SD†

- infero-basal wall, mean ± SD†

Cardiomyocytes diameter (μm), mean± SD†

SCD due to MVP

43 patients

32 (19-40)

26 (61)

4 (9)

2 (5)

2 (5)

2/26 (8)

Control

15 patients

30 (18-40)

10 (67)

2 (13)

0

0

1/10

p

0.33

0.7

1.0

1.0

1.0

1.0

8 (19)

30 (70)

5 (12)

12 (28)

10 (83)

12 (28)

4 (27)

9 (60)

2 (13)

5 (33)

0

0

1.0

1.0

1.0

-

12 (100)

8 (67)

9 (21)

0

0

0

-

357±

35

7±

±53

3

357±53

12

.6±

6±1..3

12.6±1.3

13

.0±0

.0

0±0.88

13.0±0.8

25 ((58)

58))

58

10 (23)

13 (30)

30 (70)

25 (58)

323

23±

23

± 42

323±42

12.

.5±

±3.6

12.5±3.6

112.57±0.7

2 577±0

2.

±0.7

.7

4 (2

(27)

7)

1 (6)

0

0

0

00.02

.02

2

0.9

00.08

.008

00.04

.04

04

00.25

25

-

43 (100)

38 (88)

0

0

-

30.5±10.7

33.1±7.6

19.2±6.0

6.3±1.6

6.4±1.4

12.8±0.4

<0.0001

<0.0001

<0.0001

Abbreviations: LV= Left ventricle; MVP= mitral valve prolapse; RBBB= right bundle branch block; SCD= sudden

cardiac death; VAs= ventricular arrhythmias; VS= ventricular septum.

21

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

Table 2. Clinical, ECG and CMR features of 44 patients with MVP.

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

Variables

Age, years median (range)

Female, n (%)

Symptoms, n (%)

- aborted SCD

- palpitations

tations

- syncope

ope

- chest pain

- dyspnea

nea

Therapy, n (%)

Beta-blockers

-blockers

Sotalol

lol

Otherr antiarrhythmic

anti

tiar

arrh

ar

rhyt

rh

ythm

yt

hmic

hm

ic

ICD

G

12 lead ECG

Inverted/biphasic

pha

h sic

ic T wave, n (%)

D , aV

D3

aaVF

F

- D2, D3,

- D1, aV

aVL

V

QTc duration,

n, msec

se

onit

on

itor

it

orin

or

ingg

in

ECG-Holterr m

monitoring

VPB,, n (%)

- Bigeminal

mina

mi

nall VP

na

VPB

B

- NSVT,

T n (%)

SVT, n (%)

VF, n (%)

CVAs morphology, n (%)

- LBBB inferior axis

- LBBB superior axis

- RBBB inferior axis

- RBBB superior axis

CMR Morpho-functional

Findings

LV EDV, ml/m2

LV EF, %

MVP

with

Complex VA

30 pts

Complex

VA

>3 VPB run

10 pts

Complex

VA

=3 VPB run

20 pts

MVP

without

Complex VA

14 pts

41 (28-43)

22 (73)

37 (32-43)

9 (90)

44 (36-52)

13 (65)

51 (24-64)

7 (50)

3VPB

vs

without

Complex VA

0.44

0.18

2 ((7))

15 (50)

2 (7)

2 (7)

2 (7)

2 (20)

( )

7 (70)

2 (20)

0

1 (10)

0

8 (40)

0

2 (10)

1 (5)

0

5 (36)

0

1 (7)

1 (7)

0.52

1.00

1.00

1.00

0.21

1.63

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

0.24

0.10

0.54

1.00

13 (43)

3 (10)

1 (3)

3 (10)

5 (50)

1 (10)

1 (10)

3 (100)

8 (40)

2 (10)

0

0

6 (43)

0

1 (7)

0

1.00

0.54

0.54

-

1.00

0.42

1.00

-

1.00

0.50

0.41

-

0.71

1.00

0.33

-

100 (33)

(33

3 )

9 (30)

0

2 (7)

7)

4423

23

3 (409(409-440)

9 440)

4

5 (50)

50

4 (40)

0)

2 (20)

4439

39

9 ((420-446)

420-44

446)

44

5

5 (25)

5

5 (25)

0

420 ((409-431)

4 940

9 431)

( 1))

(2

3 (21)

( 4)

(1

2 (14)

(7)

1 (7)

4412

12

2 (39

(394-432)

3 4-43

4 2))

0.55

0.5

0.46

1.00

0.19

0.220

0.

0.20

0 19

0.

0.19

0 55

0.

0.55

00.15

0.

15

00

1.00

0.67

0.41

00.34

.34

0.23

0.43

0.10

0.18

30 (100)

11 ((37)

37))

37

27 (90)

1 (3)

2 (7)

100 ((100)

100)

5 (5

(50)

0)

7 (70)

1 (10)

2 (20)

20 (1

((100)

00)

6 ((30)

30))

30

20 (100)

0

0

8 (57)

3 (2

(21)

1)

0

0

0

<0.01

00.49

.49

49

-

0.022

00.20

.20

20

-

<0.01

00.70

.70

70

-

0.43

-

0

1 (3)

13 (43)

26 (87)

0

0

7 (70)

10 (100)

0

1 (5)

5 (25)

16 (80)

0

0

0

0

-

-

-

1.00

0.05

0.27

91 (89-103)

64 (60-65)

91 (91-94)

63 (59-65)

91 (89-108)

64 (59-65)

91 (83-91)

66 (64-69)

0.13

<0.01

0.24

<0.01

0.18

0.01

0.91

0.68

22

p Value

> 3VBP

=3VPB

vs

vs

without

without

Complex VA Complex VA

0.40

0.59

0.08

0.49

>3VPB

vs

= 3 VPB

0.27

0.21

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 1, 2016

LV mass, gr/m2

RV EDV, ml/m2

RV EF, %

Posterior MVP, n (%)

Bileaflet MVP, n (%)

Lengths MV leaflets, mm

- Anterior

- Posterior

Prolapse distance, mm

- Anterior leaflet

- Posterior leaflet

contrast Findings

CMR Post-contrast

LV LGE

- papillary

lary muscles

- infero-basal

o-basal wall

mount (%)

LV LGE amount

62 (60-63)

77 (71-79)

64 (61-66)

9 (30)

21 (70)

62 (59-74)

77 (71-79)

65 (62-69)

5 (50)

5 (50)

62 (60-63)

77 (75-81)

64 (62-65)

4 (20)

16 (80)

63 (49-63)

77 (76-78)

64 (64-66)

9 (64)

5 (36)

20.7 (19.3-26.0) 20.1 (18.5-28.0) 22.1 (20.0-25.0) 20.0 (17.0-25.0)

16.0 (12.6-18.0) 14.0 (11.0-17.7) 16.3 (13.0-19.7) 11.4 (9.5-14.0)

0.48

0.35

0.43

0.05

0.05

0.55

0.51

0.93

0.68

0.68

0.57

0.39

0.27

0.01

0.01

0.75

0.91

0.31

0.12

0.12

0.32

0.02

0.51

0.26

0.34

0.01

0.65

0.27

5.1 (1.7-8.0)

7.8 (4.0-11.8)

3.3 (0-7.0)

4.5 (2.7-7.5)

5.6 (3.9-8.0)

10 (5.5-12.9)

1.3 (0-3.0)

2.1 (2.0-3.5)

0.01

<0.01

0.47

0.11

<0.01

<0.01

0.12

<0.01

28 (93)

25 (83)

22 (73)

1.2 (0.8-2.1)

10 (100)

10 (100)

7 (70)

1.1 (0.9-2.7)

18 (90)

15 (75)

15 (75)

1.4 (0.7-2.1)

2 (14)

2 (14)

1 (7)

0

<0.01

<0.01

<0.01

<0.01

<0.01

<0.01

<0.01

<0.01

<0.01

<0.0

<0

.01

01

<0.01

<0.0

<0

.011

.0

01

<0.01

<0

<0.01

0.54

0.14

1.00

0.96

Abbreviations:

s: CMR=cardiac magnetic resonance; VA= ventricular arrhythmias; EDV = End-Diastolic Volume; EF= Ejection Fraction; ICD = Implantable cardioverter defibrillator;

defibrillat LGE=

late gadolinium

corrected;

um enhancement; LBBB= left bundle branch block; LV= Left Ventricle;MVP= mitral valve prolapse; NSVT = non-sustained ventricular tachycardia; QTc = QT corre

RBBB= right bundle branch block; RV= right

rig

ight ventricle; SCD= sudden cardiac death; SVT= sustaine

sustained

ned ventricular tachycardia; VPB=ve

ne

VPB=ventricular

ent

n ricular premature beats; VF = ventricular fibrillation.

Categorical variables

ariab

ble

less ar

aree pr

pres

presented

esen

es

ente

en

tedd as num

te

number

u be

b r of patients (%). Continuous values are express

expressed

ed

d aass me

m

median

dian with 25% and 75%-iles.

23

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291

Figure Legends: