George Deltas University of Illinois, Urbana

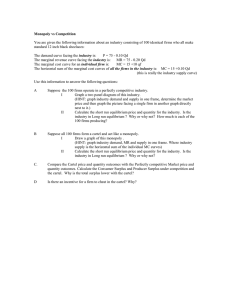

advertisement