Universal Design and the ICF - Literature Review.

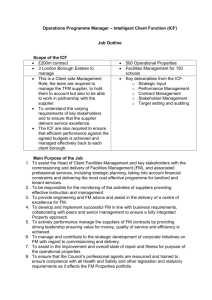

advertisement