Three Standardized Tests: Can a Storytelling Curriculum Measure Up?

advertisement

loumal of Early Chilrlhood Teacher Education, 28:251-275, Z0O7

Copyright O National Association of Early Childhood Teacher Educators

ISSN: 1090-i027 pdnt/ 1745-5642online

DOI: 10.1080/10901020701555564

!) Routledge

Taylor&FrancisGroup

fl \

@

N

-c

s

(.)

o

One Authentic Barly Literacy Practice and

Three StandardizedTests:Can a Storytelling

Curriculum MeasureUp?

c{

j-i

'o

'c

o

tL

o

o

>

d)

c)

=

=

o

o

PATRICIA M. COOPERI,KAREN CAPO2,BERNIE MATI{ES2,

AND LINCOLN GRAY3

lNew York

University, New York, New York, USA

University Center for Education, Houston, Texas, USA

3JamesMadison University, Harrisonburg, Virginia, USA

2Rice

The current study was designed to assessthe vocabulary and literacy skills of young

children who participated in an authentic literacy practice, i.e,, Vivian Paley's

"storytelling curriculum," over the course of their respectiveprekindergarten or kindergarten years, We asked: How do prekindergarten and kindergarten age children,

who participate in the storytelling curriculum over lhe course of the school year, perform on pre- and postmeasuresofAGS/Pearson Assessments'Expressive Vocabulary

Test (EVT| the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPW) (3'" ed.) Form IIIA, and

Whitehurst's Get Ready to Read!, as compared to those young children in the same

grade with similar backgrounds and in the same or similar school settings who did not

participate in the storytelling curriculum? Resuhs show that in comparison to sameage children in like settings,participants in the storytelling curriculum showed significant gains in both vocabulary knowledgeand literacy skills. Thesefindings underscore

the possibility of supporting both beginning and experiencedteachers in using authen'

tic literacy activilies to prepere childrenfor literacy learning, while maintaining their

service to a wide range of other developmental issues.They also call into question the

prevailing trend to abandon such classroom practices in favor of a skills-centered

approach to curriculum.

Introduction

ln The Child and the Curriculum,Dewey (190211990)writes of the tensionbetweenpsychology and subjectmatter in the early grades:

"Discipline" is the watchword of those who magnify the course of study;

"interest" that of thosewho blazonthe "Child" upon their banner.(p. 188)

In reading education, the tension between a child-centered vision of learning and a subject-matterbasedone has long been representedas authenticvs. skills-basedinstruction.

In actual practice, a skills approachdominated early reading curricula in the first and second grades throughout most of the last century, though the well-known "great debate"

flourished as to exactly what skills should be emphasized(Chall, 1968; Sadoski,2O04;

Stahl, 1998). A "reading readiness"curriculum, including work on shapes,fine motor

I 1 November

2006.

30 October2006;accepted

Received

to PatriciaM. Cooper,I l0 E. 14Street,#1507,New York,NY 10003.

Addresscorrespondence

E-mail:pmc7@nyu.edu

251

252

c!

iir

A

c\|

,g

(g

(L

=

3

o

P. M. Cooper et al.

skills, and conceptslike sequence,dominatedthe kindergartenyear well into the 1970s,

when direct instruction in skills becamemore common. The late 1980s and 1990switnessedthe rise of the "reading wars" betweenproponentsof phonics and whole language

approaches(Stahl). In recent years, the reading wars have given way to a "balanced"

approach(Sadoski),where authenticpracticesare comingledwith skills-basedones."Balanced literacy" is a popular idea with many teachersand teacher educators, who tout its

mix of affective and cognitive learning opportunities. Growing support for it, however,

has not countered several other trends in early literacy to be addressedin this articletrends that are threatening the future of authentic literacy activities in prefirst classrooms.

First is the pressfor accountability.In a shift from decadesof practice,the questionof

what, how, and when children learn to readis no longer the exclusivedomain of universities, teachereducationprograms,or local school districts.Increasingly,it is the privy of

federal agencies,political appointees,and for-profit entities.Under their combinedinfluence, accountabilityin early literacy learning meanssomethingnew in early childhood

of literacy subskills, often in conjunction

education:standardizedtests or assessments

goals. A prime example of an accountthat

target

specific

with state and federal standards

First Initiative (Title I, Part B) of the

is

the

Reading

ability-driven early literacy endeavor

(NCLB),

legislation passedin 2001

national

education

the

No Child Left Behind Acr

Statesand school disL2o2a.html).

(www.ed.gov/legislation/FedRegister/fi

nrulel2002-4/

five

literacy subskills in

then

test

must

teach

and

tricts that receive Reading First funding

fluency,

phonics,

vocabulary,

and comprehenphonemic

awareness,

the primary grades:

"high

associoutcomes

stakes"

funding,

other

(Yell

In

addition

to

& Drasgow,2005).

sion

rankings.

pupil

school

include

retention

and

ated with mandatedtesting

Despitethe widespreadcontroversysurroundingthe suddenrise in testingyoung children, it should be noted that the trend is not limited to children in kindergarten and the primary grades.Meisels (2006) reportsthat the "most extensiveuseof high-stakestestinghas

taken place in Head Start" (p. 2),the well-known interventionprogram for low-income 3and 4-year-olds.

The second concern of early childhood educatorsaround early literacy instruction is

the "push down" of formal reading instruction-in its historical sense of decoding and

encoding-from first grade to kindergarten, from prekindergarten to the nursery classroom. Content usually incorporateshighly formalized instruction in phonemic awareness

and activitiesrelatedto letter recognition,reproduction,and word study.Critics claim that

in order to cover test content, teachersmust make inappropriate demands on young and

very young children, including too much inactivity requiredby direct instructionand premature expectationsaround symbolic and metacognitivethinking. Just as significant is

that time spent on these academicsubskills meansa concomitantdecreasein traditional

curricula around play, story, and movement that spur oral languagedevelopmentand

allow for teacherguidancein language(Dickinson,2002; Neuman & Roskos'2005).

Early childhood educators' third and perhapsgreatestconcern is the move away from

free-rangingoral languageactivities.More than any other, this shift is likely to have prolonged impact on early literacy development,and, by extension,on all later academic

achievement(Bielmiller, 2006; Dickinson & Tabors, 2001; Scarborough,2002; Snow,

Without a strongoral languagebase,

2002; Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998;Watson,2OOZ).

young children are lesslikely to meet successin early reading.They are also likely to have

difficulty in making a timely leap from speechto writing, and thus fail to reap the reciprocal benefits of writing on reading proficiency. Clearly, the implications of an anemic oral

languageprogram in prefirst classroomsaffect all young children's experiences.Yet,

research suggests that children who enter first grade with the language habits and

Can a StorytellingCurriculum Measure Up?

@

N

v

A

N

;j

'x

(L

253

dispositionsreflective of middle classusageand child rearing practicescan still perform

adequatelyor better (Snow, Tabors, & Dickinson, 2001). The stakesare far greaterfor

children who dependon very early schoolingto preparethem to meet the languageexpectationsofthe first and secondgradecurriculum (Strickland,2000).

One persistentresponseto the oral languagedisparity betweenmiddle-classchildren

and their peersfrom lower socioeconomicgroupshas been a call for changesin parenting

norms (Barbarin,20O2).This proposalhas obviouspractical,and, to some degree,ethical

limitations.The good news is that early childhoodprogramshave long played a key role in

bridging the gap between home and school. The bad news is that given the very real limitations of time, resources,and district demands,many early childhood educatorsmust

decide,if they are given the chanceat all, betweenthe long-term advantagesof a holistic

oral language approach to early literacy and a curriculum that emphasizestest content. A

Hobbesianchoice?Or a false dichotomy?

The Problem

>

o

c

3

Influential curriculum guides for early childhood curriculum, including Learning to Read

and Write: Developmentally Appropriate Practicesfor Young Children (Neuman, Copple,

& Bredekamp,L999),describelanguage-rich,authenticactivitiesin the serviceof literacy

development,such as restaurantor firehouse"centers,"and writing activities like "postman" or snacksign-up.While theseactivitiesmeetthe usualcriteria for authenticlearning

experiences,the early childhood community has resistedassessingtheir educationalefficalled for in today's

cacy through the type of standardizedtesting or formal assessments

generally

assumedthat,

(Meisels,

is

it

2006).

For

one

thing,

climate of accountability

is

not

easily tested.

activities

impact

of

these

counterparts,

the

skills-based

unlike their

in

today's eduauthentic

curricula

measure

of

efficacy,

without

some

standard

However,

prevalent

that

they fail to

charge

vulnerable

to

the

increasingly

left

cational climate are

press

for

accountability

the

Does

this

mean

that

young

literacy.

children's

early

advance

spells the veritable end of authenticliteracy practicesin the early childhood classroom?

As noted, this presentsa theoretical and professional conflict around best practice that is

relevant to all young children (and to those who would prepare their teachers). But, a

skills-dominantcurriculum, lacking in rich and free-rangingoral languageopportunities

and play with text, poses more serious harm to young children already on the margins of

school preparednessby virtue of their inexperience with middle-class language experiences.These include children from low-income families, those whose home languageis

not StandardEnglish, and thosewhosefamilies are disengagedfrom school expectations.

This dilemma leads us to the following questionsand the focus of our study: What

happensif we take a second look at standardizedtesting and authentic literacy experiences?What might we learn from standardizedmeasurementsabout the role play-based,

language-richcurricula play in early literacy development?In other words, can the case

be made that various authentic literacy activities do not "measure up" before they are

investigated?

The Study

This article reportson a study of the impact of an acclaimedauthenticearly literacy activity, Vivian Paley's (1981) "storytellingcurriculum," on prekindergartenand kindergarten

children's early languageand literacy developmentover the course of the school year. Participantsin the study included,but were not limited to, low-incomeand English-language

254

@

N

rir

A

N

:0

n

!j

;

E

3

o

P. M. Cooper et al.

learners,who are typically marginalized by oral languageand text-related expectationsof

the standardearly literacy curriculum. After conducting a review of the relevant research,

we accepted Meisel's (2006) claim that "accountability calls for information about

whetheror not somethinghappened"(p, 17).Given the high ratio of teacher-childinteractions around language and text inherent in Paley's storytelling curriculum (described

below) analogousto that found in middle-classhomes,we hypothesizedthatregular participation might have a positive impact on participants' vocabulary and knowledge of

beginning skills-two essentialcomponentsof an early literacy skill set. We looked to

well-known and commonly used assessments,

designedto measurethe degreeto which

individual children possesstheseparticular attributes(Gullo, 2006). We asked:How do

prekindergartenand kindergartenagechildren, who participatein the storytellingcurriculum over the course of the school year, perform on pre- and postmeasuresof the Expressive Vocabulary Test (EVT), the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Zesr (PPVT), and

Whitehurst's Get Ready to Read! (GRTR!) as comparedto those young children in the

samegrade with similar backgroundsand in the sameor similar school settingswho did

not participatein the storytellingcurriculum?Mindful of the many negativeaspectsassociated with testing of young children, we sought to eliminate or reduce these by, first,

allowing the children time to be comfortablewith the researchersthrough repeatedvisits

to the classroomprior to assessment,

and, second,allowing the children to decideagainst

pafiicipation in both pre- and posttesting.

Significance

The significanceof this study lies in its mergerof severalconcernsfacing the early childhood community today: the push for accountabilityregardingyoung children's early literacy learning;the push down of academicexpectationsinto the prefirst grades;the push in

of culturally biased expectationsaround oral language and literacy experiences;and,

finally, the push out of curriculum that focuseson broader developmentalissues.The

"usesof storytellingin the classroom"(Paley, 1990)embraceinclusive,play-based,holistic relianceon story in the serviceof psychosocialdevelopment,which has beenlinked to

literacy and narrative development (Cooper, 2OO5; Mclane & McNamee, 1990;

Nicolopoulou, 1996, 1997).The storytellingcurriculum's impact on young children'soral

languageand literacy subskill developmenthas not been assessedpreviously, however.

An underlying question for this article is whether it "measuresup" as a prototype for

authenticliteracy activities that serveboth developmentand academicendsfor all children.

Oral Language Development

The body ofliterature on young children's oral languagedevelopmentis large and beyond

the scopeof this article. We have, therefore,limited our review to the characteristicsof

oral languagedevelopmentat school entry that is consideredrelevantto short- and longterm literacy learning. A separatesection is provided on the storytelling curriculum.

A salient thread throughout the researchis that young children's early literacy success,and thus their long-term profiles, is most predicatedon their oral languagecharacteristics at school entry when they are between5 and 6 yearsold. More notably, successful

characteristicsare highly correlatedwith middle-class(especiallyWhite and professional)

usage, as well as competenciesderived from middle-class child rearing practices around

languagein the first 5 years of life (Snow et al., 2001). Vocabulary developmentis one

example. Hart and Ristley (1995, 2003) find that by their third birthday middle-class

Can a Storytelling Curriculum Measure Up?

N

-c

I

s

-i

N

;J

:p

(L

c)

o

O

;

0)

(o

E

3

o

255

children "have heard 30 million more words than underprivilegedchildren." This fact

alone advancesmiddle-classchildren's receptiveand expressivevocabularies,linguistic

ability, reflectivereasoning,abstractthinking, and overall backgroundknowledgein ways

privilegedby schoolexpectations.

Similarly,Snow and Dickinson (1991) write that middleclasschildren are also habituatedfrom infancy into the understandingand use of decontextualizedlanguage.The Early Childhood Learning s/rd), (ECLS) (U.S.Departmenrof

Education, 1998) reports that young White children-significantly overrepresented

among the middle class-regularly outperform their African American peers--disproportionately underrepresented-onmeasuresof early reading subskills,including beginning

sounds,ending sounds,and letter recognition.

Middle-class parents also advantagetheir prefirst children by directing their attention

to text and print in ways that cultivate comprehensionskills. For example, story-related

talk often includes such observationsas, "The third little pig was the smart one, wasn't

he?" Understandingthe reciprocity between print and talk is assistedthrough regular

informal experiences(such as respondingto environmentalprint, learning letters, and

drawing) that lead to writing. Finally, Heath's(1983) seminalstudy of parent-child talk in

different racial and socioeconomiccommunitiesfinds that middle-classparentsfurther

advantagetheir preschoolchildren educationallythrougha style of verbal communication

that prefiguresnot only the teacher'sforthcoming question-and-answer

expectations,but

orientstheir children towardsthe overall demandsof texts as relatedto school tasks.

Early childhood advocacyorganizations,in particularthe National Associationfor the

Educationof Young Children (NAEYC), have long emphasizedauthentic,or "naturalistic" (Gronlund,2006), oral languagepracticesbetweenteachersand children. NAEYC's

highly influential program of Developmentally Appropriate Practice (Bredekamp &

Copple, 1998)recommendsthe following:

Teachersencouragechildren's developinglanguageand communicationskills

by talking with them throughout the day, speakingclearly and listening to

their responses,and providing opportunities for them to talk to each other.

(p.127)

Further recommendationsinclude engagingindividual children and groups in conversation about real experiences.Watson (2002) writes that certain forms of talk, such as metalanguage and abstraction, are more relevant in literate cultures as a result of literate

influences,and that children's proficiency in them leadsto a bidirectional learningcurve

wherein the more competent they are in and about the language of texts, the more texts

they can read, and competencyincreases.when applied to early schooling, CochranSmith (1984) and othersreport that "read-alouds"are instrumentalin this process.Parallel

to and woven throughout languageexperience,Bredekamp and Copple also advocate

embeddingprint and writing opportunitiesin authenticactivities,including:

learning particular names and letter-soundscombinations and recognizing

words that are meaningful to them (such as their names,names of friends,

phraseslike "I love you," and commonly seen functional words like exlt).

(p.l3l)

The historical bias towards autheltic literacy activities in prefirst early childhood

education reverberatedin the whole languagemovement of the 1980s and 1990s (see

Goodman,1986; Goodman& Goodman,1979).The differenceis that. whereasthe former

256

N

rir

:c!

jj

'^

'tr

n

L.

>

m

E

3

o

P. M. Cooper et al.

was long associatedwith the prereadingphase,the latter is seen as reading and writing

instruction in the primary gradesand throughoutelementaryschool. Stahl and Miller's

(1989) review of the literatureon whole language,however, found its greatervalue in a

"readiness"perspective,including kindergarten,ratherthan a beginningreadingand writing one.

Teachersare seento play different roles in fostering languagedevelopment.Dickinson and Sprague(2N2) suggestthat, althoughteachersmay becomesurrogatementorsof

languageand continue to foster young children's oral languagedevelopmentaway from

home, they may possibly underutilize their potential impact on languagedevelopment

when engagedin direct instruction.They report that teachersengagemore in intentional,

efficacious conversationsand more talk about past and presentevents during free play

than in large group times focusedon specificskills. Others(Stahl& Miller, 1989;Watson,

2002) caution that an emphasis on oral language development without a concomitant

emphasison featuresof print will not advanceemergingliteracy in the classroom.

The Storytelling Curriculum

Paley introduced the storytelling curriculum in Wally's Stories: Conversations in the Kindergarten(1981) without referenceto its usefulnessto oral languagedevelopmentor literacy subskills. For Paley, its main purposethen, and in all recent iterations, is to offer

young children an opportunity to tell their classmates"what they are thinking about"

(p. 66). Its tools are what Paley refers to as storytelling and story acting, also referred to by

Cooper (1993,2005) as dictation and dramattzation.In brief, though the storytelling curriculum varies somewhatfrom classroomto classroomand teacherto teacher,it has two

basic components.The first is the dictatedstory, in which the teacher-or scribe-is an

active participant,freely asking questionsthat help clarify the child's intention ("Is this

part a dream or did the little boy wake up? Should I write that?"). Sometimes,she offers

assistance("Are you thinking of the 4th of July?"), and, in a variation on Paley's original

plan (Cooper,2005), sometimesinstruction("Look here, a thword, like we talked about

in the mini-lessontoday"). Story contentis almost always,if not exclusively,determined

by the child. The secondcomponentis the dramatizationof the story by the authorand his

or her chosen classmates.In this part, the teacheracts as director, while the remaining

children constitutethe audience.Again, the teacherreservesthe right to interrupt,as she

talks with the author and actors about staging, improvising dialogue, and so on. As a

result,the ensuingdramaresemblesrehearsalmore than openingnight.

Guidelinesfor implementationcan be derived from Paley (1981; 1992,1997,2004).

Cooper (L993,2005) offers a methodologicaloverview basedon extensiveprofessional

development with teachersin the Houston area and colleaguesin the School Literacy and

Culture Project in the Rice University Center for Education. One feature of the storytelling

curriculum that is especially relevant to the study is its inclusion of second-language

learnersin classroomswhere all instructionis conductedin English. Teacherscooperate

on a variety of methods, from key vocabulary and peer assistanceto small objects and

"show me," to help the child seehis or her story written down and actedout, howeverlimited his or her English proficiency. (SeeFigure I for a methodologicaloverview.)

Though dictation and dramatizationactivitieswere not new to early childhood education when Paley (1981) wrote Wally's Stories: Conversationsin the Kindergarten, she

gets credit for bundling them into a unified and regular focus of classroomlife (Cooper,

2005). The storytellingcurriculum fits Donovan,Bransford,and Pellegrino's (2003) definition of an "authenticlearning"opportunityin that it allows participantsto "meaningfully

Can a Storytelling Curriculum Measure [Jp?

zJ/

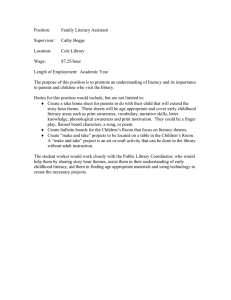

Methodologicar overview of parey's storytelring curricurum

c{

Storytelling/Dictation

o

$

A

N

.T

'-

'tr

!i

o

o

>'

ct

C)

E

=

o

Where children sil The child/author should sit to the left of right-handed teacher/

scribe and to the right of left-handed ones so that the teacher's arm does not block the

c h i l d ' sv i e w o f t h e w r i t i n g .

carbon paper Carbon paper is used to make an instant copy of the story so that

the child can take one home and the teacherhas one to read to the classand later put in

the child's file or portfolio or ClassBook of Stories.

Name and date Before the child begins to dictate, the teacherwrites his or her

name in the left-hand corner and the date in the right. The teachershould say out loud

what she is writing.

How to begin First-time storytellers might need some help to get started. Others

are too shy or inexperiencedto dictate stories at first. It's okay to offer suggestions

until the child gets used to the process.("I really like those new sneakers.would you

like to tell a story about the day you went shopping?")Sometimesit's merely a matter

of offering a beginning or a way in. ("Some storiesbegin 'One day' or 'Once upon a

time' or 'Once there was a little boy.' Would you like to startthat way?")

Length Stories are limited to one page due to time restrictions.Children who

pressto tell more shouldbe taughtaboutinstallments,chapters,and "to be continued."

Subiect matter The fewer the restrictions on subject matter the better (except the

obvious-bathroom stories,explicit sexuality,unkind descriptionsof other children,

and so on,)

Echoing As the teacherwrites, she echoesback to the child what he or she has

just said. ("One-day-a-bear-came-to-dinner."

This keeps both teacher and

child on track as it calls attentionto the words being written.

A hesitunt storyteller If the child hesitatesbetween thoughts, the teachercasually

encouragesher or him to proceed.("Yes? And then what happened?"or "Okay. Go on.

I'm ready.")

Wrifing and narative developmenl The teacherhelps the child expand on his or

her thought by engaging in a conversationabout the story. ("Wow! You must have

beenreally scaredwhen the monstercame.Did you scream?Would you like to put that

in the story?What did the baby do that madeeveryonelaugh?") Sometimesit helpsfor

the child to think aheadto the dramatization.("Tell me what the kids are going to do

when they are tigersin the play. Maybe you could put that in your story aheadof time.")

Skill development The teacher indirectly points out or asks questions about

decoding,such as beginning sounds,doubleconsonants,and rhymes.Occasionallyshe

asks the child to spell a word that is a challengefor him or her. ("Do you remember

how to spell floor?") Grammar and grammarand punctuationminilessonscan also be

easily inserted.("Where shouldI put the quotationmarks?")

Figure 1. Methodologicaloverview of Paley's storytellingcurriculum.

258

N

-c

rif

(f)

A

N

.-T

(o

'tr

I

ri

o

(J

;

d]

o

=

3

o

P. M. Cooper et al.

Editing and revision Editorial questionsregarding sequencing,narrative development, and so on can be askedof the storytellerat any time. (..so, your mama took you

to the storeand then to school.Is that right?) Dictatedstoriesare rarely revised,though

they can be if a child desiresto.

Read the story after it is done When the child is finished dictating, rhe reacher

rereadsthe story to make sure she "got it right." She automaticallymakesany changes

the child requests.

Choosing the cast After finishing reading the story, the teacherreminds rhe child

that he or she needsto choosea cast.First, she calls attentionto the possiblecast by

underlining the charactersin the written story. It is assumedthat the author will play

the lead,though this is not a requirement.The child chooseshis castfrom the classlist,

noting who has not had a turn yet in this cycle. He or shemay chooseas many characters as there is room on the classroom's"stage" (dramatizationarea).Usually this will

be four to six actors and covers the main charactersin most stories.When necessary,

the audienceis askedto "imagine the rest" of the characters.The teacherwrites the cast

namesand their partson her copy of the story becauseit is difficult to rememberwho's

who when it comes time to dramatize later in the day.

Extra tip Teachers should be upbeat, involved scribes. ("No kidding? Oooh,

that's scary." "Hey, I like this part where the fire engine talks." "A deep blue, gooeygobbly day?-I love itt")

Story Acting/Dramatization

Keep it simple Do not think in termsof rehearsalsor props.

Gather the class in u semicircle The teacher begins by announcing who wrote a

story that day. In turn, she asks eachauthor to come standbesideher while she reads

the classhis or her story.

Calling the cast The teacherannounceswho in the classwill play which roles and

ask them to come stand"offstage." (A small rug helps to mark the spot. Actors move

on to the stageas required.)

Reread while cast acts out the story As the teacherrereadsthe story once more,

the chosenactorsact as the story line dictates.

Dialogue The teacher pausesbefore any dialogue to see if the child remembers

his or her lines. If not, the teachersimply repeatsthem, and the child repeatsafter her.

Improvisationis welcome,exceptwhereit changesthe author'sintent or distractsfrom

the overall play.

Directing the action The teacher should feel free to interrupt the dramatization

with suggestions.("Zoe, the little bear is very upset to find his porridge eatenall up.

Can you look upsetlike the little bear would?")

Curtain call After "The End" the actors ioin hands and take a bow while the

audienceclaps.

Figure l, (Conrinued)

Can a Storytelling Curriculum Measure Up?

Dramatization of Adult.authored Stories

@

c!

v

A

N

jj-

259

children love to act out adult-authoredbooks,too. This is a key opportunity for them

to learn how good storiesare constructed(beginnings,middles, ends, problem, solution, and so on). It also extendstheir vocabularyand knowledgeof sophisticatedsentencestructure.The methodis the sameexceptusually the teacher,not a child, chooses

the cast.Dramatizationof a favorite book can occur as many as five to a dozen times

beforethe children want to move on.

Figure1. (Continued).

(!

'tr

t'

0)

o

;

c0

E

3

o

o

constructconceptsand relationshipsin contextsthat involve real-world problemsthat are

relevantand interesting."To be clear, "real-world problems" in the courseof very young

children's storytellingare mostly psychosocialin nature(e.g.,sibling rivalry) and, though

often borrowedfrom real life (e.g.,good guys vs. bad guys) are usuallyfiltered throughthe

imagination.As such, it is ideally suitedto children's explorationsin language,from the

use of new vocabulary, to moving in and out of tenseand time frames, to the articulation of

decontextualized and abstract thought, exemplary of what Snow et al. (2001) refer to as

"extended discourse" in which all new readersand writers must become proficient. (See

Figure 2 for samplestories and a sampleexcerptfrom transcript.)From this perspective,the

ability to tell coherent stories is a by-product of both scaffolding (vygotsky, 1978) and

function. For teachers,the storytelling curriculum provides a model through which they can

model narrative discourseand createopportunitiesfor children to try their hand at it.

Researchers

have investigatedthe storytellingcurriculum from a variety ofpsychosocial angles(Cooper, 1993;Dyson, 1997;HurwiCI,200l; Katch, 2001,2003; Nicolopoulou,

Scales,& Weintraub,1994;Sapon-Shevin,1998;Sapon-Shevinet al., 1998;Wiltz & Fein,

1996).Researchon its direct relationshipto literacy developmentincludesa focus on narrative development(McNamee,Mclane, Cooper,& Kerwin, 1985; Nicolopoulou, 1996,

1997).Wolff (1993) theorizesthat, as describedby Paley, telling and acting out stories

fostersthe child's ability to move beyond "here-and-now"languageto "there-and-then,"

an essentialtask of namativedevelopmentand comprehension.In addition, Cooper(1993,

2005), Dyson (2002), Dyson and Genishi (1993), and Mason and Sinha (1993) arguethat

the storytellingcurriculum offers informal-but-deepsupportfor young children's acquisition of secondaryliteracy subskills,including symbol making, and conceptsabout print.

Again, to date, no study has investigatedthe impact of the storytelling curriculum on

young children's pre- and postperforrnanceon standardizedand formal assessments

of

oral languagedevelopmentand literacy subskills.

Method

The study was designedto comparecontrol (3) and treatment(3) public school classroomsof

same-gradechildren in the same school district or school building, representingtwo school

districts.All teacherswere expectedto follow the school-mandatedliteracy curriculum.

Research Team

All membersof the researchteam were at the time of the study closely associatedwith the

School Literacy and Culture Project in the Rice University Centerfor Education.All have

260

P. M. Cooper et al.

Pretest story from Ramon, ELL prekindergarten male

@

N

October 14,2004

(g

$

(f)

A

N

I played in the block center.Build car. Right there gamecenter.Bus bumpy. play cars.

I like play playdough.Library. Sandtable.Play outside.

The End

ji

Posttest story from Ramon, ELL prekindergarten male

'.E

April27,20OS

n

f

(D

The Running Big Bad Wolf

x

m

=

3

o

A big bad wolf killed all the people.He ate them. He went to the park and ate the fish.

The shark was in the water. The shark ate the bad wolf. The shark was playing with

him friends. They drink water.The alligator was in the water, too, They were fighting.

The alligator won. He went to drink from the water fountain.He went to the park doing

exercise.The daddy at the water fountain said,"Stop fighting."

The End

Sample transcript of teacher (J/child (G) interactions during story telling/dictation

Giovanni's Story

October 16,2005

J:

"Stand over here 'causeI want to be close by you. A1l right Mr. Giovanni. Let's

put your name G - I - O - Vanni. This is Giovanni's sixth story! you ready?

Do you have a good idea for your story?What's it going to be about?"

G: "A silly wolf."

J:

"A silly wolf-I can't wait to hearit!"

G: "And he was flying!"

J:

"He is silly! He had wings?"

G:

"Yeah, he made it out of paper."

J:

"Oh, I cannotwait to hearthis story...so'A silly wolf was flying.' Is that how you

want to start it?"

G: (nods)

J:

(Echoes& writes) "Tell me againhow he did that."

G: "He made his wings out of paper."

pre-andpoststories

Figure2. Sample

andsample

transcipt.

Can a Storytelling Curriculum Measure Up?

J:

N

-c

o

o

v

5

261

(E&W) (Pause)

G: "He didn't know how to blow houses

downbecause

all of themweremadeout of

bricks."

J:

"Ah, OK." (E&W)

G: "He pickedon. . .thechicken.. .he,he,he.. .pickedon thewolf andhe wentlike.

'ow !" '

N

J:

.g

o

n

G:

J:

j

g

>

m

"He picked on him or he peckedon him? Which word?',

'?ecked

on him."

"He pecked." (Echoes as she writes) "The chicken, he pecked-that's a good

word"- goesback to writing "he peckedon the wolf and he said-What?"

G: "He said,'Yowl"'

J:

q)

"Yowch!" (Chuckles) "oK... So thar poor wolf, rhe poor silly, flying wolf got

peckedby a chicken,huh?" (Chuckles)"And he said, 'yowch!," (pause)

(5

G: "A dog came and bit him."

E

;o

J:

"He's having a very bad day." (E&W) "A dog came and bit him."

G:

"He said nothing."

J:

"He said nothing?He wasjust quiet aboutthat, huh? Do you want me to write 'He

saidnothing'?"

o

G: (Nods)

J:

(E&W)

G: "And then a bearcame."

J:

"Oh no, I notice your animals are getting bigger and bigger-first one was little,

then a middle-sizedanimal, now he's gonna get this bear." (Preparesto write.)

"Did you say a big bear orjust a bear?"

G: "A big bear."

J:

"Then a big bear-"

G: "A big, big hugeBEARI"

J:

(Chucklesat his enthusiasm)"A big, huge bearcame." (E&W)

G: "Then he knocked him on the head."

J:

(Chucklesagain) "He knockedhim on the head." (E&W) "Then what?"

G: "He stilled."

J:

"He stilled?You mean he was frozen like that?"

G:

"He is frozen and he can still move."

Figure 2. \Continued).

262

J:

N

-c

s

A

N

.q

J:

|t

::

o

;

o

"He was knocked on the headand that madehim like frozen, like that?" (Dramatizes)

G: "Uh-huh. And then someoneput water on him and the ice came off him."

J:

"oh! so he was still-he was frozen," (writing) "And then what happened?Someone did what?"

G:

(Unintelligible)

J:

"wait a minute, let's go back to the frozen part." (Rereads)"He was still, he was

frozen. You said somethingabout someonepouredwater..."

G:

"They poured water on the ice and then it, he, he, the water got off him."

J:

(Writing) "So, they pouredwateron the ice..."

G:

"Then it got off the wolf."

J:

(E&W) "Can I ask you a quesrion real quick? Who is they'/ Who poured rhe

water?"

G

4

o

"He can still move?"

G: "Uh-huh.He was frozenand..."

ji

F'r

P. M. Cooperet al.

G: "Jaylen."

J:

"Jaylen." (Laughs,writes "Jaylenpouredwater on the ice.")

G: "I want to make a long story!"

J:

"It's getting pretty long! OK, so now your wolf is not frozen any more, so then

what did he do-the flying silly wolf?"

G: (Pause)

J:

"He's not frozen any more so he can do whateverhe wants."

G:

"The bearput him on a jelly bean."

J:

"On a jelly bean? So now I've got a wolf sitting on a jelly bean? Is this true?"

(Laughs)"OK." (Rereadsthe last two sentences

quickly) "The wolf got on..."

G: "The title is 'The Wolf."'

J: "The title is 'The Wolf?' That's right, becauseit's all about a wolf. OK, so the

wolf got on. . .what color were thejelly beans?"

G: "Yellow."

J:

"OK, can I put that in your story?The wolf got on the yellow jelly bean."

G:

(Nods)

J:

(E&W) "Then what happened?"

G: "He ate it."

J:

(E&W) "Did he like jelly beans?"

Figure2. (Continued).

Can a Storytelling Curriculum Measure [Jp?

@

G:

(Nods)

J:

"Did you want me to write that-'He liked jelly beans'-orjust skip it?,'

N

o

6

G: (With enthusiasm)"Write it!"

(E&w) "oh, I wish I had an artisr who could draw a picrure of a flying wolf who

likesjelly beans...Allright." (Rereadslastsentence)

.i-

J:

A

C.l

ii

G: "Then there was a girl who ate the whole wolf."

-T

J:

"A girl-like

G:

(Nods)

J:

(E&W) "Then there was a girl. . .whardid shelook like?"

"She looked like an Indian 'causeshe was brown."

'^

f

o

;

c]

E

G:

a peoplegirl?"

J:

"Should I put that in?" (E&w) "Then therewas a girl. She looked like an Indian."

(Interruptionfrom child sayingthey found a cocoon.J says,"Good for you!" then

returns to the story.)

J:

"She looked like an Indian becauseshe was brown. (Pause)An Indian from India

or a native American?"

=

o

o

263

G: "From Asia."

J:

"Should we put 'She was from Asia?"'

G:

(Nods)

J:

(E&W) "All right." (Rereadslast two sentences."She looked like an Indian

becauseshe was brown. She was from Asia.") "Now tell me again what this girl

did."

G:

"She ate the wolf."

J:

"OK. She ate the wolf."

G:

"And then a boy came and a bear.They looked the same!"

J:

(Distractedby anotherchild) "And then a boy came."

G: "And then a bear."

J:

(E&W)

G: "And they looked the same!"

J:

"The boy and the bear lookedjust the same?"(E&W)

G: "It's getting closer!"

J:

"Yes, you've about got your whole page here." (Rereads'And then a boy came

and then a bear.They looked the same.')What did they do?"

G: "They went to a person."

Figure 2. (Continued)

264

P. M. Cooper et al.

"Who?"

"They went to an artist."

N

o

o

J:

s

"Can I write that?That's a good word." (E&w) "oK, and what did they do when

they found the artist?"

"They said, 'Hello,' and then they went back".

A

N

(Writes with no echo) "What did rhe artist do?"

JJ

.-?

"He was painting...he was paintinga flying wolf that likesjelly beans."

:s

"They said hello and then they went back. should I write what the artist was

doing?"

j

(Agrees)

c)

o

o

"So how should I say it?"

>

"The artist was writing a flying wolf that likesjelly beans."

Q)

(Chuckles)"OK, was he writing or painting?"

=

3

"Painting."

r\

"OK, The artistwas paintinga flying wolf...we're at the end."

"We're almost thereso we can get a long story."

"It's long, but you've got to leave me some spacebecausewe've got a lot of

friends in this story." (Finishesechoingand writing) "That liked jelly beans."

"It's almost getting closer."

"It's very close 'causewe have to have room to write here. Shall I read it to you

first, then we'll pick whose gonnabe in it? 'The Wolf. A silly wolf was flying. He

made his wings out of paper.He didn't know how to blow housesdown because

all of them were made of brick. The chicken, he peckedon the wolf and he said,

"Yeowch!" The dog came and bit him. He said nothing. Then a big, huge, huge

bear came and he knocked him--oh, I skipped a word-he knocked HIM on the

head.He was still. He was frozen.Jaylenpouredwater on the ice and it got off of

him. The wolf got on a yellow jelly bean.He ate it. He liked jelly beans!Then

there was a girl. She looked like an Indian becauseshe was brown. She was from

Asia. She ate the wolf. Then a boy came and then a bear. They looked the same.

They went to an artist and they said hello and then they went back. The artist was

painting a flying wolf that liked jelly beans.'That's awesome.So who's gonnabe

the silly (laughing)flying wolf?"

"Julius."

J:

"Of coursehe is." (Juliusis G's good friend and he had also walked up to the table

during the last few sentencesof the story.)

G : "Jerald's sonnabe the chicken."

Figure 2. (ContinueQ

Can a StorytellingCurciculumMeasure [Jp?

"I thoughtToby was gonnabe it, but that'sa goodpick. Jeraldneedsto be in this story."

(Another child. "Chicken? Chicken is a funny name,")

co

N

o

J:

"This class loves that word!" (Brief aside as J explains to researcher

that Toby

started that. "when he first came to pre-K he liked to call people .chicken

Head.'we askedhim not to call peopleanimal names,so then, in order to get the

namechicken in he would say somethinglike 'chickenpot pie' and it's the way he

saysit that everybodyjust roars,so now chicken'sa funny word.")

J:

"All right, we've got a chickenhere.who's gonnabe the huge,huge bear?"

rq

N

i)

..7

'6

n

'j

265

J.

"Oh we skippedsomebody.We needa dog."

G: (Answerspreviousquestion)"Allejandro."

J:

"We needa dog."

G : "That's gonnabe Ms. Mandelli." [The studentteacher.]

;

J:

o)

G : "Uh-hum."

E

J:

=

"Ms. Mandelli. She'll do a goodjob. And you said Ailejandro will be the bear?"

"And Jaylen-who's gonnabe Jaylen?Jaylencould be his own self."

G : "Toby. And Julius is going to be the chicken."

"No, you said Jerald,Julius is going to be the flying wolf."

(Julius:"I can be the chicken and the flying wolf too.")

J:

"No, you have to just be one. OK, we needa girl-an Indian girl from Asia."

G: "Shairah."

J:

"And we needa boy."

G: "That's gonnabe Alexia."

J:

"Alexia" (a girl) "is going to be a boy? And I need an artist-is thar going to be

you? Who's gonnabe the artist?"(Pause)"You're not in the story, do you want to

be in it?"

G: "I want to be the artist."

J:

"OK, I didn't want you to forget yourself.OK, we're done."

G: "Now it's time to clean up."

Giovanni's story

The Wolf

"A silly wolf was flying. He made his wings out of paper.He didn't know how to blow

housesdown becauseall of them were made of brick. The chicken, he pecked on the

wolf and he said,"Yeowch!" The dog cameand bit him. He said nothing.Then a big,

huge,huge bearcame and he knockedhim. He knockedHIM on the head.He was still.

Figure 2. (Continued).

266

@

N

o

s

P. M. Cooper et al

He was frozen.Jaylenpoured water on the ice and it got off of him. The wolf got on a

yellow jelly bean. He ate it. He liked jelly beansl rhen there was a girl. She looked

like an Indian becauseshe was brown. She was from Asia. she ate the wolf. Then a

boy came and then a bear.They looked the same.They went to an artist and they said

hello and then they went back. The artist was painring a flying wolf that liked jelly

beans."

A

The End

N

ji

Figure2. (ContinueA.

(s

'c

!j

>

c0

c)

(!

E

3

o

considerableexperiencein both implementingPaley's storytelling curriculum and conducting related professionaldevelopment.Cooper (1993, 2005) has written previously

about it. Capo and Mathes acted as mentors to the three treatmentclassroomteachers

aroundthe storytellingcurriculum.After severalvisits to eachclassroomto get acquainted

with the children so as to make participationin the study easier,they also conductedthe

pretesting and later the posttesting, Capo and two other researcherscollected data on

teacher-child interactions as stories were dictated and acted out. This latter data was not

analyzedfor this study.

Classroom Selection

The study took place in two public prekindergarten,kindergarten,and mixed-aged classrooms in lower-and mixed-income communities in southeastTexas. Treatment and control

classroomswere groupedas pairs with matching grades,community and family demographics, and school-mandatedcuniculum. Approximately 7570of the study children qualified for

free or reduced lunch. Roughly half of the participants,including all of the prekindergarten

classroomsand the treatmentkindergartenclassroom,were designatedas English Language

Learners(ELL). Although qualificationsfor ELL designationvariesfrom district to district

and even school to school, all of the children had been evaluatedby school personnelas

competentenough in English to participatein the study and perform reliably on the selected

instruments.All classroominstructiontook place in English. Both the kindergartenand

mixed-agetreatmentand control classroomswere in the sameelementaryschool building.

Becauseone of the prekindergartentreatmentclasseswas the only one in the building with

ELL students,district administratorsidentified a class in another elementary school that

matchedthe treatmentschool in ethnic makeupand family backgrounds.

Treatment Classroom Teachers

Each treatmentclassroomteacherhad participatedpreviously in a professionaldevelopment program conductedby the researchteam on Paley's storytelling curriculum. Each

had implementedit for at least I year prior to the study,and had servedas a mentor to new

residentsin the program.Dictation and dramatizationof children's stories,the core of the

curriculum, as well as ongoing dramatizationof quality children's literature,took place

routinely in each of theseteacher'sclassroomat least four times per week. In the study

year, each treatmentteachertaped the storytelling process.The storytelling curriculum

was consideredan addition to eachschool'srecommendedliteracv curriculum.

Can a StorytellingCurriculum Measure Up?

267

Control Classroom Teachers

N

!

\r

;i

c!

u

:g

f

o)

::

o

E

3

o

The control classroomteacherswere randomly assignedto the study by virtue of

the factors mentioned above. None of the control teachershad received professional

development in the storytellingcurriculum, though all had attendedan information session

on the

study. (SeeFigure 3 for an overview ofdescriptive data.)

Subject Participation

Approximately 92Vo of 124 children in both control and treatment classrooms

returnedpermissionslips to participatein pre- and posttesting.Regardlessof permission to participate,all children receiveda picture book for returning the permission

form' All teachersreceived a box of books to supplementtheir classroom library.

Every effort was made to obtain pre- and posttestmeasureson each eligible child,

though children were allowed to refuse to participateat any point, and severaldid.

Some scores could not be obtained due to continuing absences,families moving

away, and schedulingconflicts. In the end, pre- and postscoreswere obtainedfrom 95

children.

District permissions,identification of control classrooms,and parental permission

were obtainedby early November,when pretestingbegan.Posttestingbeganin mid-April,

beginning with the classroomsthat were testedfirst during the pretestingsessions,allowing for approximately4.4 monthsfrom pretestto posttestfor all subjects.

Treatment

Although all children in the classroom participated in the dictation and dramatization

activities, only those children with parental permission were followed for the study.

Participating teacherseach took dictation and then dramatizedchildren's stories4 days

a week. Stories from quality children's picture books or other forms of literature were

acted out by small groups of children on the 5th day. The dictation processgenerally

required l0 to 15 minutes of one-on-oneteacher/childinteraction per story. Two classrooms set the goal of recording and acting out two children's stories each day, while

the third teacher chose to do only one. Neither is an unusual schedule in storytelling

classrooms(Cooper, 2005), though Paley strongly statesa preference for greater frequency (personalcorrespondence).In each ofthe classrooms,teacherstook dictation at

a classroom table in full view of the other children in the class. Teachers sat directly

besidethe participatingchild, positioningthe paperso that the child could clearly see

what was being written down. Teachersechoedeach storyteller'sdictated words as

they scribed to ensure that the children's words had been captured exactly as intended

or modified, if necessary.Teachersalso pausedto ask both clarifying and extension

questions.Stories were limited to one page in length due to time constraints.At the

story's close, the author chose which classmateswould representgiven charactersin

the forthcomingdrama.All dramatizations

took placethe sameday in which the stories

were dictated. Children were asked to imagine props and nonessentialcharacters.

Teachershelped extend the children's dramasearly in the year by asking prompting

questionsor having the audiencesuggestpossibleways to act out a given part. As the

year continued,children took over greatercontrol of the director's role in their own

dramatizations.

'Q

I

ca

(\

E

o!:

+.?

{)v

x

v

:

A

c{

I

ra)

';.i

'tr

13

o

n

E"E= ; $

!.)

ea

=

cgy

c.)

tr\J

7

f+,qir

-..

9E

gR!

=

g'

s

:

+. csc6.

I r E9; !n

i,;q

A e ==

rE: 5

*

..

a9!t

o

0)

X>

9,

I

F

J

E;

F

ra:; :I 5 Er+s

ieFa

I

c)

3

E

S $:!72v

s

.=

>

Ra

g

o

I

5R

F.:r

e

;

s:Ec =i! EE?

fiF5'"

'.1

-!.1

RL

!

i:

b-

"

6-a

tlE

E

irr

e

9ie

EiEPei

E:a;,.==

\.,r

i5

E'

tr0..66

S,P

Bft t !>

E

Hgi E: E

Eou

E

c.t

0.

t"

(-)

i:

h tr

[ -E e

i; sE

F+HiEsFs

JgEE"

i e H ; e g t:

_ > oh E

:

tr

r

v;

a

^-=

+A

Fi;gEEgr

l!BE

g-

;,

!- F.:

ifla#Ef! e5,FE,t-ts:5;!-

*

;

E ,!,

ts!

7

q

a

rn

g.F's#

$gifu5,

F

!

?n

u!

&

Lxl

vx&

g:;ii'r

v -^

.92

Y^

s h

'B

\

a^

= F.=

tr.F

-di E

<

?. * >

i

EE!

d!

a=

ts

gr

'sa.2

gEaa;EF,EF*g

2 -l

# !EH

s s::- tsd

EiH

-;Eeefr

ds"!iir

t H:F

L;: !h E E;

oi

o

H

.o

-

O.

'd

g!e AE

b

-,8e i'a

E

IE;EEE ={ E

-a=sir$

as!;E gFgFe-s* !

E -q=;5* 5"o*=

; !

268

Can a Storytelling Curriculum Measure (Jp?

269

Assessments

N

\t

The researchteam chosecommonly acceptedand widely usedmeasures

of children's oral

language and early literacy knowledge. The prekindergartenchildren

were given the

Expressive vocabulary Test (EYT) and the peabody picture vocabulary zesr (ppvr),

as

well as Whitehurst's Get Ready to Read! (GRTRI) screeningtool for kindergarten

readiness.The kindergarten children were given the only the EVT and the ppvr.

N

Findings

'F

o

g

L:

o)

;

@

(!

=

=

o

A priori it was determinedthat subjectswould needto have valid pre- and posttestscores

on both the PPVT and the EVT to be includedin the analysis,as the basicmeasureof analysis is change from pre- to posttestscore.Through this criterion, a basic data set was

established,sincethesetwo measureswere administeredto all subjects.The basicdata set

included58 (32 pre-w26 K) treatmentsubjectsand37 (16 pre-w2l K) controls.

As indicatedin Figure 4, the importantresult is that the changesin both the PPVT and

GRTRI testswere significantly greaterfor the children in treatmentclassrooms(p . .05,

one-tailed).Changein each test was defined as the postscoreminus the prescorefor each

child. An independentsamplest-test(SPSS,chicago,IL, version r2.o,2oo3) was usedro

evaluatethe null hypothesesthat there was no differencebetweenthe treatmentand control classroomsin any of the changescores(PPVT, GRTR!, and EVT) versusthe hypothesis that the treatmentgroups improved more. Homogeneityof variancewas satisfiedfor

all comparisons(p > .5).

children in the treatmentclassroomsimproved an averageof 4.5 points (+ 1.0 sem)

on the PPVT, while children in the control classroomsimproved only an averageof 0.7

points(+ 1.3 sem).This differenceis significanr(t90 =2.23, p = 0.013, l-tailed) and rhe

x

2a

?

-

!q3

';

?z

C

270

@

c{

-c

o

v

;{

c\|

!

'i\

'tr

n

f

o

;

o)

=

3

o

P. M. Cooper et al.

effect size of this differenceis 0.49, which is consideredto be

a moderateetl'ectand to be

educationallysignificant.

children in the treatmentclassroomsimproved an averageof 4.0 pornts (+

0.7 sem)

on the GRTR!, while children in the control classroomsimproved only

an averageof 1.7

points (+ l.l sem).This differenceis significanr(r4t = l.g, p = 0.03b,

t_taileajandthe

effect size of this difference is 0.60, which is consideredto be between a moderate

and

large effect and to be educationallysignificant.

There was no significant difference between children in the treatment and control

classroomsin their changeon the EVT (190= 0.95, p = 0.175, l-tailed), though the differ_

ence was in the predicted direction with treatmentclassroomsshowing slightly greater

improvement (4.5 + 1.1) than control classrooms(2.9 + 1.3). standard power analysis

(Cohen, 1988) suggeststhat significantly greaterimprovement after treatmentcould be

demonstrated(a = .05, F = .2) with278 childrenin eachgroup or about six times the effort

hereinaccomplished.

Figure 4 shows the changes in each of the three tests in both treatment and control

classrooms.Positive changesindicatethat the scoreimproved. To summarizethe significant results,the PPVT and GRTR test scoresimproved more in the treatmentclassrooms.

Figure 5 shows the averagepre- and posttestscoresfor the PPVT and for the GRTRI

testsin the treatmentand control classrooms.None of thesemeansare different between

the treatmentand control classrooms(p t .13 for the pretestsand p > .65 for the posttests,

respectively).The trend in the treatmentclassroomsbeing more steeplyupward was evaluated with the change scores describedabove. Significance in the individual change

scores(Figure 4) and not in the group means(in Figure 5) indicatesthat each individual

needsto be their own control (by comparingpre- versusposttestscores)in order to detect

the effect of the treatmentin this sample.Such subject-to-subjectvariance within each

group is expected.

Discussion

In her most recent book, A Child's Work: The Importance of Fantasy Play (2005),Paley

writes that, if academicsuccessis the goal, the early childhood community cannotafford

to dispensewith a play-basedcurriculum.Like many advocates(Pelligrini & Galda, 1993)

PPVT

MPE

Figure5. Pre-andposttest

meanson thePPVTandGRTR!

Can a Storytelling Curriculum Measure (Jp?

N

(s

s

N

'tr

j

c]

0)

o

=

3

271

of a traditional, play-basedearly childhood curriculum in the kindergartenand

below,

Paley arguesthat the best preparationfor later academicsuccess,from symbolic thinking

to comprehensionto problem solving, is the developmentof the imaginationthroughplay.

This study does not reject or attemptto measurethe storytellingcurriculum's impact

on the young child's imaginationor other developmentalgoals.It was designedto ask if it

meets more standardizedgoals, specifically vocabulary (ppVT and EVT) and reading

readiness(GRTR!). Findings reveal that both English LanguageLearners and Englishonly speakerswho participatedin the storytelling curriculum made significant gains in

vocabularyknowledge,as measuredby the PPVT. They further suggestparticipationalso

significantly impactedprekindergartenchildren's performanceon the GRTRI Though in

the predicted direction, flat scoreson the EVT for both groups are hypothesizedto be

relatedto the children's English limitations,despitethe districrs' appraisalof rheir abilities. Researchersfelt that in contrastto the PPVT and GRTR!, the demandfor expressive

languageon the EVT exceededmany of the children's expertiseor comfort level at that

time.

The importanceof the findings relatedto the PPVT and GRTRI is immediateand significant for teachersand teachereducatorsinterestedin Paley's storytelling curriculum.

The findings extend the storytelling curriculum's educationalefficacy beyond its established psychosocialand narrativevalue to specificacademicgains increasinglynecessary

to justify implementation.The significanceis amplified by the fact that its participants

were consideredgreatly at risk for entering first grade without sufficient languageand lir

eracy skills, including lower income, nonstandardEnglish speakers,English Language

Learners, and other children whose home life cannot guaranteethe free-ranging oral languageexperiencesaroundthe creationand explorationoflanguage and text that are imitative of middle-classhomes and associatedwith early literacy successin school. The

findings should also be of great interestto teachers,teachereducators,and advocatesof

authenticearly literacy curricula in general.

In recentyears,the limited empirical evidencedemonstratingthe academicrelevance

of such practicesin the classroomhas left teachereducators,teachers,and other school

district personnelunpreparedto defend their selectionof them. First, looking beyondthe

storytellingcurriculum, the findings underscorethe gainsto be had in preservingthe early

childhood tradition of authenticearly literacy curricula,and call into questionthe prevailing trend to abandonsuchfree-rangingoral languagecurriculain favor of a skills-centered

approachto early literacy.Working backwardsfrom the outcomes,the findings ultimately

lead to the question that most concernsteachereducatorsand teachers:What notable

aspectsof the storytelling curriculum account for the children's progress in language

developmentand skill knowledge?That is, what happensinside the curriculum to support

early literacy successin theseareas?Which aspectsof the story telling curriculum might

be most appropriateto integrateinto the literacy curriculum of teachereducation?

Transcript analysisand story contentsuggestfour aspectsof storytelling curriculum

are plausibly responsiblefor its success,which may haveapplicationto other authenticliteracy curricula.The first is the way in which the storytellingcurriculum marrieslanguage

experimentationand explorationto young children's living and learning agendas.Dictation and dramatization,which dependon languageand little else, make it possiblefor

them to sharewhat happenedlast night, to satisfytheir curiosity about the squiggleson the

paper, or to act like superheroeson stagewith their friends. Hence, their motivation to

becomestorytellers-language users-increasesautomatically.In addition,it makessense

that as children get more experiencewith the processand more exposureto the possibilities of languageto convey their ideas more accurately,their vocabulary increasesand

272

6

N

o

sf

o

N

'o

(U

!j

o

;

o

-9

=

o

P. M. Cooper et al

languageuse matures,as doestheir knowledgeof print. A glanceat the sample

setof stories from ELL prekindergartner Ramon (Figure 2) reveals an over 200Vo increase

in the

sheernumber of words in his story from the beginningof the study to the end. Even

more

telling is his growth in sentenceconstructlonand semantics.

october 14,2004. "I played in the block center.Build car. Right there game

center.Bus bumpy. Play cars.I like play playdough.Library. Sand table.play

outside.The End."

April 27, 2005. "The Running Big Bad wolf A big bad wolf killed all the

people. He ate them. He went to the park and ate the fish. The shark was in the

water. The shark ate the bad wolf. The shark was playing with him friends. They

drink water. The alligator was in the water, too. They were fighting. The alligator won. He went to drink from the water fountain. He went to the park doing

exercise.The daddyat the waterfountainsaid, 'Stopfighting.' The End."

The secondfactor in the storytelling curiculum's successappearsto be the way in

which languageand knowledge of print is teacherfostered and scaffolded (Vygotsky,

1978).As the sampletranscript(Figure2) reveals,the processrequiresteachersto engage

in informal, but directed interactionswith individual children, highly imitative of discourseinteractionsin middle-classhomes.For example,the teacher(J) in the sampletranscript engagesthe child (G) throughlanguagethat is inferential,inviting, and personal,yet

it never fails to lead G on. Her openingstressesboth use and skills, startingwith attention

to the lettersthat begin his name,and movesquickly to clear narrativeexpectations,

J: "Stand over here 'causeI want to be close by you. All right Mr. Giovanni.

Let's put your name - G - I - O - Vanni. This is Giovanni's sixth story! You

ready?Do you have a good idea for your story?What's it going to be about?"

The child, in turn, acceptshelp from the teacher to both express and

expandhis ideasas sheputs them on paper.

J: "Oh no, I notice your animalsare gettingbigger and bigger-first one

was little, then a middle sized animal, now he's gonna get this bear.

Did you say a big bear orjust a bear?"

G: "A big bear."

J: "Then a big bear-"

G: "A big, big hugeBEARI"

J: (Chucklesat his enthusiasm)"A big, hugebear came."

He allows her to help him attend to the sounds of words and other

nuancesof language.

G : " H e p i c k e do n . . . t h e c h i c k e n . ,. h e ,h e ,h e . . . p i c k e do n t h e w o l f a n d

he went like, 'OW!'

J: "He picked on him or he peckedon him? Which word?

G: "Peckedon him."

J: "He pecked.(Echoesas she writes) The chicken, he pecked-that's a

good word-he peckedon the wolf and he said . . . . What?"

Can a Storytelling Curriculum Measure Up?

N

$

\r

(f)

N

ij

'.?

.G

6

;

c0

0)

-9

B

o

273

Thesetype of interactionsalso occurredwhen young childrendictatedportlons

or versions

of their favorite children's books, thus strengtheningthe children's relationship

to and

commandover common texts.

Teachersand teachereducatorsmay also want to considertwo other findings in the

datathat go well beyond the goals of this study,but that we hypothesizeimpact the storytelling curriculum's potential for languageand literacy development.They are worth nor

ing becausethey are so often overlooked in preparing young children for academic

achievement.The first is the inclusive natureof the dictation and dramatizationactivities.

As Ramon's stories suggest,no proficiency in any area of development,including language and subskills, is required to tell storiesor act them out. There is no possibility of

failure or needfor remediation.The only criterion is, as noted at the beginningof the article, "interest" (Dewey, 1902/1990).In this case,it is the desireto join the community of

storytellersand actors.Second,interestin participationis possibly increasedby the fact

that a common practice in the three storytellingclassroomsis the free choice of content.

Inspirationmay have come from a book. But it may also havecome from home,the television, the movies, or a peer.Borrowed and repeatedthemesare frequent.In this sense,the

storytelling curriculum validates who the children are, what they know, and what they

careabout.When combinedwith the other aspectsof the processdescribedabove,the storytelling curriculum offers young childrenfair and unrestrictedaccessto and growth in the

"discipline" (Dewey) of languageand literacy.

Conclusion

The positive impact of Paley's storytelling curriculum on young children's vocabulary

and skills knowledge suggeststhat it is a viable alternativeto the skills-dominant and

teacher-neutralearly literacy curricula increasingly prevalent in prefirst classrooms

aroundthe country. As such, it offers a model of what curriculum can look like and what

teacherscan do to supportearly literacy successthat is as child friendly and inclusiveas it

is effective.Findings direct researchers,

teachereducators,and teachersto continue their

advocacyof both the storytelling curriculum and other free-ranging,teacher-scaffolded

oral languageopportunitiesin the early childhood classroom.As discussed,the current

climate of accountabilityhas increasedthe needfor early childhood classroomsto provide

curricula that representfair and equitableimitationsof home life, relevantto the academic

demandsof the upper grades.To this end, the needfor early childhood teachersto retain

their historical focus on oral language-based

curricula that are directedat fair and equitable goalsfor young children-like the storytellingcurriculum-has never been greater.

References

Bielmiller, A. (2006).Vocabularydevelopment

andinstruction:A prerequisitefor schoolleaming.

In S. B. Neuman& D. K. Dickinson(Eds.),Handbook

of earlyliteracyresearch,Vol.2 (pp.4l-51).

New York: Guilford.

Chall,J. (1970).karning to read:Thegreatdebate.NewYork: McGraw-Hitl.

Cochran-Smith,

M. (1984).Themakingof a reader.Norwood,NJ: Ablex.

Cohen,J. (1988)Sralislicalpoweranalysisfor the behavioralsciences.

Hillsdale,NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum.

Cooper,P. (1993).Whenstoriescometo school:Telling,writing,andperformingstoriesin theearly

childhoodclassroom.New York: Teachers& WritersCollaborative.

Cooper,P. M. (2005).Literacylearningandpedagogical

purposein VivianPaley's'storytelling

curriculum'. Journalof Early ChildhoodLiteracy,5(3), 229-251.

aa/

@

N

$

:{

c!

jj

'i

'tr

G

f

>

c0

o

=

=

o

o

P. M. Cooper et al.

Dewey, J. (1990). The child and the curriculum. Chicago: University of Chicago press. (Original

work published1902)

Dickinson, D. K. (2002). Shifting images of developmentally appropriate practice as seen

through

different lenses.Educat i onal Researc her, 3 I (1), 26-32.

Dickinson, D. K. & Sprague, K. E. (2002). The nature and impact of early childhood care environments on the language and early literacy development of children from low-income families. In

S. B. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early riteracy research, vol. 2 (pp.263280). New York: Guilford.

Donovan, S. M., Bransford,J. D., & Pellegrino,J. w. (Eds.).(zoo3). How people learn: Bridging

research and practice. Washington, DC: National Academy press.

Dyson, A. H. (1997). Writing superheroes:Contemporary childhood, popular culture, and classroom

literacy.New York: TeachersCollege Press.

Dyson, A. H. (2002). Writing and children's symbolic repertoires:Developmentunhinged.In S. B.

Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research, vol. 1 (pp. 126-14l).

New York: Guilford.

Dyson, A. H., & Genishi, C. (1993). Visions of children as languageusers:Languageand language

education in education in early childhood. In B. Spodek (Ed.), Handbook of research in the educat ion of y o ung ch il d r en (pp.122*136). New York : Macmillan.

Goodman,K. (1986). What's whole in whole language?Portsmouth,NH: Heinemann.

Goodman, Y., & Goodman, K. (1979). Leaming to read and write is natural. In L. Resnick &

A. Weaver (Eds.),Theoryand pracrice in early reading (pp. 137-154).Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Gullo, D. F. (2006). K today: Teachingand learning in the kindergafien year. Washington,DC:

National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Hart, B., & Risley, T. (2003). The early catastrophe.

Americon Educator, 27(l),4-9.

Hurwitz, S. C. (2001). The teacherwho would be Vivian. YoungChildren, 56(5),89-91.

Katch, J. (2002). Under deadman's skin: Discovering the meaning of children's violent play. New

York: Beacon.

Katch, J. (2003). They don't like me: kssons on bullying and teasingfrom a pre-school classroom.

New York: Beacon.

Mason, J. M., Sinha, S. (1993). Emerging literacy in the early childhood years: Applying a

Vygotskian model of Ieaming and development.In B. Spodek (Ed,), Handbook of research in the

educationof young children (pp.137-150).New York: Macmillan.

Mclane, J. 8., & McNamee, G. D. (1990). Early literacy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

McNamee,G. D., Mclane, J., Cooper,P. M., & Kerwin, S. M. (1985),Cognition and affect in early

literacy development. Early Child Developmentand Care, 20,229-224.

Meisels, S. (2006). Accountability in early childhood: No easy answers (Occasional paper, 6).

Chicago: Erikson Institute.

Neumann,S. 8., & Roskos,K. (2005).Whateverhappenedto developmentallyappropriatepractice

in early literacy? YoungChiLdren,60(4),22-27 .

Nicolopoulou, A. (1996). Children and narratives: Toward an interpretive and sociocultural

approach.In M. Bamburg,Namative Development:SixApproaches(pp. 179-215).Mahwah, NJ:

Erlbaum.

Nicolopoulou, A. (1997). Narative developmentin social context. In D. I. Slobin, J. Gerhardt,

A. Kryatza,& J. Guo (Eds.),Social interaction,social context,and language: Essaysin honor of

SusanErvin-Tripp (pp.369-390). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Nicolopoulou,A., Scales,B., & Weintraub,J. (1994).Genderdifferencesand symbolic imagination

in the storiesof four-year-olds.In A. H. Dyson, & C. Genishi,C. (Eds.),The needfor story: Cultural diversity in classroom and community (pp. lO2-123). Urbana, IL: NCTE.

Paley, V. (1981). Wally's stories: Conversations in the kindergarten. Cambndge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Paley, V. (1990). The boy who would be a helicopter: The uses of srorytelling in the classroom.

Cambridge,MA: Harvard University Press.

Can a Storytelling Curriculum Measure Up?

N

o

(!

s

A

N

ji

:g

(L

o

;

c0

o

E

3

275

Pellegrini, D. & Galda, L. (1993). Ten years after: A reexaminationof symbolic

play and literacy

research.Reading Research euarte rly, 2B(2), 162_175,

sadoski, M. (2004). conceptual foundationsof teachingreading.New york: Guilford.

Scarborough,H. (2002). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities:

Evidence,theory, and practice.In S. B. Neuman& D. K. Dickinson (Eds.),Handbook of early

literacy research,VoL I (pp.97-l l0). New york: Guilford.

Snow, C. E.' & Dickinson, D. (1991). Skills that aren't basic in a new conceptionof literacy. In

E. M. Jennings & A. C. Purves (Eds.), Literate systemsand individual lives: Perspectiveson literacy and schooling (pp. 179-191).Albany, Ny: stare University of New york press.

snow, c. 8., Tabors, P. o., & Dickinson, D, K. (2001). Languagedevelopmentin the pre-school

years. In D. Dickinson & P. Tabors (Eds.), Young childrenlearning at home and school: Beginning with literacy and language (pp. l-26). Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Stahl, S. (1998). Understanding shifts in reading and its instruction. Peabody Journal of Education,

73(3& 4),31-67.

Stahl,S., & Miller, P. D. (1989).Whole languageand languageexperienceapproachesto beginning

reading:A quantitativeresearchsynthesis.Reviewof EducationalResearch,39(l),97-116.

U.S. Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics. (1998). Earty Childhood

Learning Study. Kindergarten class of 1998-1999. Washington, DC: Office of Educational

Researchand Improvement.

Watson, R. (2002). Literacy and oral language:Implicationsfor early literacy acquisition.In S. B.

Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research, Vol. I (pp. 43-53).

New York: Guilford.

Wiltz, N. W., & Fein, G. G. (1996).Evolution of a narrativecurriculum: The contributionsof Vivian

Paley. YoungChildren, 51(3), 6l-68.

Wolfl D. P. (1993). There and then, intangible and internal: Namativesin early childhood. In

B. Spodek (Ed.), Handbook of research in the education of young children (pp. 42-56). New

York: Macmillan.