Performance Analysis of 12S-10P Hybrid

advertisement

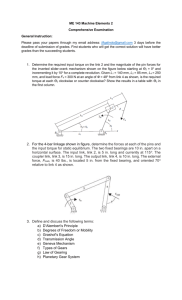

The 2nd Power and Energy Conversion Symposium (PECS 2014) Melaka, Malaysia 12 May 2014 Performance Analysis of 12S-10P Hybrid-Excitation Flux Switching Machines for HEV Nurul ‘Ain Jafar, Siti Khalidah Rahimi, Siti Nur Umira Zakaria and Erwan Sulaiman, Department of Electrical Power Engineering, Faculty of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia, Locked Bag 101, Batu Pahat, Johor, 86400 Malaysia aienjafar@yahoo.com and erwan@uthm.edu.my Abstract- Research and development on flux switching machines (FSMs) have been emerged as an attractive machine recently due to their unique characteristics of all flux sources located on the stator allowing a simple and robust rotor structure whilst providing high torque and power density suitable for various applications. They can be categorized into three groups that are permanent magnet (PM) FSM, field excitation (FE) FSM, and hybrid excitation (HE) FSM. Both PMFSM and FEFSM has only PM and field excitation coil (FEC), respectively as their main flux sources, while HEFSM combines both PM and FECs. In this research, design and performance of a three phase 12S-10P HEFSM in which the field excitation coil (FEC) located external to the PM are investigated. Initially, the design procedures of the proposed machine including parts drawing, materials, condition and properties setting are explained. Then, coil arrangement test is analyzed to all armature coil slots to confirm the polarity of each phase. Moreover, the flux interaction analysis is performed to investigate the flux capabilities at various current densities. Finally, torque and power performances are investigated at various armature and FEC current densities. I. INTRODUCTION A demand for vehicles using electrical propulsion drives is getting higher and higher from the standpoints of preventing global warming and saving fossil fuel recently. Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEVs) which combine battery-based electric machines with an internal combustion engine (ICE) have been manufactured to reduce the pollutant emissions that can cause global warming due to demand of personal transportation. As viable candidates of electric machines for HEV drives, there are four major types of electric machines, namely, DC machines, induction machines (IMs), switch reluctance machines (SRMs), and permanent magnet synchronous machines (PMSMs) as illustrated in Fig. 1. DC machines should be widely accepted for electric vehicles (EV) and HEV drives because they can use a battery as a DC-supply as it is and have an advantage of simple control principle based on the orthogonal disposition of field and armature mmf. However, the essential problem of dc drives, which is caused by commutator and brush, makes them less reliable and unsuitable for a maintenance-free drives [1-5]. IMs are widely accepted as the most potential candidate of non-PM machine for the electric propulsion motor in HEVs due to their reliability, ruggedness, low maintenance, low cost and ability to operate in hostile environments. Moreover, low efficiency at low speed-light load region of HEV drives due to the secondary loss may essentially degrade fuel consumption or system efficiency. Furthermore, IM drives have some drawbacks such as necessity of high electric loading to realize high torque density and low power factor, which are more serious for the large power motor and that push them out from the candidate race for HEV electric propulsion system [6-7]. (a) DC (c) IM (b) IPMSM (d) SRM Fig.1. Four major candidates of electric machines for HEV drives SRMs are gaining much interest as non-PM machine and are recognized to have a potential for HEV drive applications. They have several advantages such as simple and rugged construction, low manufacturing cost, fault tolerant capability, 221 The 2nd Power and Energy Conversion Symposium (PECS 2014) Melaka, Malaysia 12 May 2014 simple control and outstanding torque speed characteristic. Thus, SRM can inherently operate with an extremely long constant-power range. Nevertheless, several disadvantages such as vibration and acoustic noise, larger torque pulsation, necessity of special converter topology, excessive bus current ripple and electromagnetic interference noise generation make them unattractive [8-10]. As one of the vehicles, many automotive companies have commercialized Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEVs) in which Interior Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (IPMSM) have been employed as a main traction motor in terms of high torque and or power density, and high efficiency over most of operating torque-speed range. This is due to the restriction of motor size to ensure enough passenger space and the limitation of motor weight to reduce fuel consumption. As an example, the historical progress in the power density of main traction motor installed on Toyota HEV show that the power density of each motor employed in Lexus RX400h ‟05 and GS450h “06 has been improved approximately five times and more, respectively, compared to that installed on Prius ‟97 [11-12]. Even though the torque density of each motor has been hardly changed, a reduction gear has enabled to elevate the axle torque necessary for propelling the large vehicles such as RX400h and GS450h. As one of effective strategies for increasing the motor power density, the technological tendency to employ the combination of a high-speed machine and a reduction gear would be accelerated. With the significant achievements and improvements of permanent magnet materials and power electronics devices, the brushless machines excited by PM associated with FEC are developing dramatically. This type of machine is called hybrid excitation machine (HEM) that can be classified into four categories. The first type consists of both PM and FEC at rotor side such as combination rotor hybrid excitation (CRHE) machine and synchronous/PM hybrid AC machine [13]. The second type consists of PM in the rotor while FEC is in the stator [14]. The third type consists of PM in the rotor while the FEC is in the machine end [15-16]. Finally, the fourth type of HEM is the machine, which has both PM and FEC in the stator [17-18]. It should be emphasized that all HEMs mentioned in the first three have a PM in the rotor and can be categorized as “hybrid rotor-PM with field excitation machines” while the fourth machine can be referred as “hybrid stator-PM with field excitation machines”. Based on its principles of operation, the fourth machine is also known as “hybrid excitation flux switching synchronous machine (HEFSSM)” which is getting more popular recently. HEFSSM with all active parts, namely permanent magnet, DC field excitation coil and armature coil located on the stator has an advantage of robust rotor structure being similar to the switch reluctance machine (SRM), which makes it more suitable for high-speed drive applications compared to “hybrid rotor-PM with field excitation machines” and conventional IPMSM [19]. Moreover, since all active parts are located in the stator body, it is expected that a simple cooling system can be used for this machine compared with a water jacket system used in IPMSM. In addition, the additional DC FEC can also be used to control flux with variable flux capabilities. Various combinations of stator slot and rotor pole for HEFSSM have been developed for high-speed application. For example, 12Slot-10Pole HEFSSM has been proposed such as in [20-21]. However, the proposed machine has a separated PM and Ctype stator core that makes it difficult to manufacture, and the design is not yet optimized for HEV applications while the machine in [22] has a limitation of torque and power production in high current density condition. In this paper, based on the topology of HEFSSM discussed above, a combination of 12Slot-10Pole HEFSSM that proposed for HEV applications is demonstrate in Fig. 2. The proposed machine is composed of 12 PMs and 12 FECs distributed uniformly in the midst of each armature coil. In this 12Slot-10Pole machine, the PMs and FECs produce six north poles interspersed between six south poles. The threephase armature coils are accommodated in the 12 slots for each 1/4 stator body periodically. As the rotor rotates, the fluxes generated by PMs and mmf of FECs link with the armature coil alternately. For the rotor rotation through 1/10 of a revolution, the flux linkage of the armature has one periodic cycle and thus, the frequency of back-emf induced in the armature coil becomes ten times of the mechanical rotational frequency. Generally, the relation between the mechanical rotation frequency and the electrical frequency for this machine can be expressed as fe Nr . fm where fe is the electrical frequency, fm is the mechanical rotation frequency and Nr is the number of rotor poles respectively. 222 Armature coil Stator Rotor Shaft Permanent Magnet Fig. 2. Proposed design of 12S-10P HEFSM FEC The 2nd Power and Energy Conversion Symposium (PECS 2014) Melaka, Malaysia 12 May 2014 II. Fig.3. principle operation of HEFSM (a) θe=0° (b) θe=180° flux moves from stator to rotor (c) θe=0° and (d) θe=180° flux moves from stator to rotor OPERATING PRINCIPLE OF HEFSM The term flux switching is created to describe machines in which the stator tooth flux switches polarity following the motion of a salient pole rotor. All excitation sources are located on the stator with the armature coils and FECs allocated to alternate stator teeth. The advantages of this machine are easy cooling of all active parts in the stator and robust rotor structure that makes it better suitability for highspeed application compared to conventional IPMSM. On the other hand, the field excitation can be used to control flux with variable flux capabilities. Generally, the FSM can be categorized into three groups that are permanent magnet flux switching motor (PMFSM), field excitation flux switching motor (FEFSM), and hybrid excitation flux switching motor (HEFSM). The operating principle of the proposed HEFSM is illustrated in Fig 3, where the red and blue line indicate the flux from PM and FEC, respectively. In Fig 3 (a) and (b), since the direction of both PM and FEC fluxes are in the same polarity, both fluxes are combined and move together into the rotor, hence producing more fluxes with a so called hybrid excitation flux. Furthermore in Figure 3 (c) and (d), where the FEC is in reverse polarity, only flux of PM flows into the rotor while the flux of FEC moves around the stator outer yoke which results in less flux excitation. As one advantage of the DC FEC, the flux of PM can easily be controlled with variable flux control capabilities as well as under field weakening and or field strengthening excitation. III. DESIGN RESTRICTIONS AND SPECIFICATIONS The design restrictions and specifications of the proposed HEFSM for HEV applications are listed in TABLE 1. The electrical restrictions related with the inverter such as maximum 650V DC bus voltage and maximum 360A inverter current (Arms) are set. By assuming only a water cooling system is employed as the cooling system for the machine, the limit of the current density is set to the maximum of 30Arms/mm2 for armature winding and 30A/mm2 for FEC. The outer diameter, the motor stack length, the shaft radius and the air gap of the main part of the machine design being 264mm, 84mm, 30mm and 0.7mm, respectively. In the other hand, the target maximum torque and power is 303Nm and 123kW, respectively. The weight of PM is limited to 1.3kg. Commercial FEA package, JMAG-Studio ver.13.0, released by JRI is used as 2D-FEA solver for this design. TABLE 1. Design Restrictions and Specifications HEFSM 650 360 30 Items Max. DC-bus voltage inverter (V) Max. inverter current (Arms) Max. current density in armature winding, Ja (Arms/mm2) Max. current density in excitation winding, Je (A/mm2) Stator outer diameter (mm) Motor stack length (mm) Shaft radius (mm) Air gap length (mm) PM weight (kg) Max. torque (Nm) Max. power (kW) 30 264 84 30 0.7 1.3 303 123 IV. DESIGN RESULTS AND PERFORMANCES BASED ON FINITE ELEMENT ANALYSIS (a) (b) (c) (d) A. Coil Arrangement Test In order to validate the operating principle of the HEFSM and to set the position of each armature coil phase, coil arrangement tests are examined in each armature coil separately. Initially, all armature coils and FEC are wounded in counter clockwise direction. The flux linkages of each coil are evaluated and the armature coil phases are classified according to conventional 120° phased shifted between all phases or called as U, V, and W. Fig. 4 displays the flux linkage at condition of PM with high FEC current density. Moreover, the magnetic flux linkage in all conditions is in the same phase with essential sinusoidal waveform. The maximum amplitude of flux linkage generated under this condition is approximately 0.11619Wb. 223 The 2nd Power and Energy Conversion Symposium (PECS 2014) Melaka, Malaysia 12 May 2014 Flux[Wb] U V amplitude of induced voltage generated is also increased up to 340.90V and becoming more distorted. W 0.15 Je=0 A/mm2 Je=30 A/mm2 Emf[V] 0.1 Je=15 A/mm2 400 0.05 300 200 0 0 30 60 90 120 150 180 210 240 270 300 330 360 100 -0.05 Electric Cycle[°] 0 0 -0.1 30 60 90 120 150 180 210 240 270 300 330 360 -100 -0.15 Electric cycle[°] -200 Fig. 4. UVW phase of magnetic flux -300 B. Flux Linkages The flux path of the proposed HEFSM produced by both PM and FEC with maximum current density Je of 30 A/mm2 is demonstrated in Fig. 5. From the figure, it is obvious that the flux flow from stator to the rotor and return through nearest rotor pole to complete one flux cycle. Moreover, most of the fluxes are distributed and saturated at rotor air gap. Nevertheless, huge number of fluxes flow into rotor in high gap flux density can lead the unnecessary flux leakage and flux cancellation. Besides, more flux flow into the rotor can cause higher back-emf which is unnecessary for the system. -400 Fig. 6. Back emf at 1200r/min rated speed D. Cogging Torque The cogging torque profile of the proposed HEFSM under the conditions of PM only, FEC only and combination of PM and FEC is depicted in Fig. 7. Obviously, 6 cycles of cogging torque are generated to complete one electric cycle. The peakpeak cogging torque of PM only and PM with maximum FEC current density Je of 30 A/mm2 are approximately 32.244Nm and 28.187Nm, respectively. It is clear that the cogging torque of PM only is slightly higher than PM with maximum FEC current density due to weakening effect of the flux linkage. Since the cogging torque values produced must not exceed 10% of the average torque, the generated cogging torque of the proposed HEFSM is unnecessary for the performance of the machine due to production of high vibration and noise. Therefore, further design refinement and optimization should be conducted to get the target torque and reduce the cogging torque. Torque [Nm] 20 PM Only Je=30 PM + Je=30 15 Fig. 5. Flux line of PM with maximum current density, Je of 30A/mm2 10 C. Induced Voltage The induced voltage of the proposed machine is generated at the speed of 1200 r/min. Fig. 6 illustrates the open circuit waveforms of the proposed design for different current density conditions. The voltage with Je of 0A means that the induced voltage is generated from flux of PM only. The amplitude of fundamental component is 258.23V and is slightly sinusoidal. When the Je is varied from 0 A/mm2 to 15 A/mm2, the amplitude of induced voltage is increased to 301.10V. This is due to the strengthening effect by the additional generated flux of FEC. With increasing Je to the maximum of 30 A/mm2, the 224 5 0 0 30 60 90 120 150 180 210 240 270 300 330 360 -5 -10 Electric Cycle[°] -15 -20 Fig. 7. Cogging torque The 2nd Power and Energy Conversion Symposium (PECS 2014) Melaka, Malaysia 12 May 2014 E. Torque vs FEC current density, Je at various armature current densities, Ja characteristics The drive performances of the initial design machine in terms of torque versus FEC current density characteristics of the proposed motor is plotted in Fig. 8. The graph shows that with increasing in Je, the torque also increase linearly with the same pattern at 0Arms/mm2 until 15Arms/mm2. Meanwhile, similar torque characteristic is obtained at 20Arms/mm2, 25Arms/mm2 and 30Arms/mm2 in which the torque pattern is constant. The maximum torque is approximately 183.32Nm when Ja of 20Arms/mm2 and Je of 30A/mm2 are set. This is due to low armature coil flux that limits the force to move the rotor. To overcome this problem, design improvement and optimization will be conducted in future. Torque[Nm] 250 200 150 184.70Nm 100 50 Electric cycle[°] 0 0 30 60 90 120 150 180 210 240 270 300 330 360 Fig. 9. Instantaneous torque characteristics Ja=0 Ja=15 T[Nm] Ja=5 Ja=20 Ja=10 Ja=25 V. CONCLUSIONS In this paper, performances analysis of the proposed HEFSM for HEV application has been presented. The coil arrangement test have been carried out to identify each phase of armature coil and to locate the initial position of the rotor. The performances of the proposed motor such as flux capability, cogging torque and back-emf characteristic have also been investigated and demonstrated. The initial design performances demonstrate that the design refinement is required to achieve the target performances. Thus, by further design modification and optimization, the target performances HEFSM are expected can be achieved. 200 180 160 140 120 100 80 60 40 Je A/mm2 20 0 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 Fig. 8. Torque vs Je at maximum Ja F. Instantaneous torque characteristic at maximum current density condition Furthermore, the instantaneous torque characteristics at maximum torque condition in which the FEC current density and armature current density are set to 30A/mm2 and 30Arms/mm2, respectively as demonstrated in Fig. 9. The average torque reaches 184.70Nm with the peak-peak torque of approximately 43.26Nm. Since the peak-peak torque is higher than required minimum value, estimation of flux linkage which contributes to high cogging torque will be investigated and optimized. VI. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This work was supported by UTHM Scholarship from Centre of Graduate Studies, Universiti Tun Hussein Malaysia (UTHM), Batu Pahat, Johor. VII. REFERENCES [1] C. C. Chan, “The state of the art of electric, hybrid, and fuel cell vehicles”, Proc. IEEE, vol. 95, no. 4, pp.704– 718, Apr. 2007. [2] A. Emadi, J. L. Young, K. Rajashekara, “Power electronics and motor drives in electric, hybrid electric, and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles”, IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron., vol.55, no.6, pp.2237-2245, Jan. 2008. [3] D. W. Gao, C. Mi, and A. Emadi, “Modeling and simulation of electric and hybrid vehicles”, Proc. IEEE, vol. 95, no. 4, pp.729–745, April 2007. [4] G. Dancygier and J. C. Dqlecagaray, “Motor control law and comfort law in the Peugeot and Citroën electric vehicles driven by a dc commutator motor”, Proc. IEE— Power Electron. and Variable Speed Drives Conf., Sep. 21–23, 1998, pp. 370–374.M. [5] E. Sulaiman, S.N.U Zakaria, T. Kosaka and N. Matsui, “Design And Analysis of 12-Slot 10-Pole Permanent Magnet Flux-Switching Machine With Hybrid Excitation 225 The 2nd Power and Energy Conversion Symposium (PECS 2014) Melaka, Malaysia 12 May 2014 for HEVs”, International Journal of Energy & Power Engineering Research, Vol, 1, pp. 1-5, Dec 2013 [6] C. C. Chan, “The state of the art of electric and hybrid vehicles”, Proc. IEEE, vol. 90, no. 2, pp. 247–275, Feb. 2002. [7] T.Wang, P. Zheng, and S. Cheng, “Design characteristics of the induction motor used for hybrid electric vehicle”, IEEE Trans. Magn., vol. 41, no. 1, pp.505–508, Jan. 2005. [8] J. Malan and M. J. Kamper, “Performance of a hybrid electric vehicle using reluctance synchronous machine technology”, IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl., vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 1319–1324, Sep./Oct. 2001. [9] X. D. Xue, K. W. E. Cheng, T. W. Ng, N. C. Cheung, “Multiobjective optimization design of in-wheel switched reluctance motors in electric vehicles”, IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron., vol.57, no.9, pp.2980-2987, Sept. 2010. [10] S.M.Lukic, A. Emadi, “State-switching control technique for switched reluctance motor drives: Theory and implementation”, IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron., vol.57, no.9, pp.2932-2938, Sep. 2010. [11] R. Mizutani, “The Present State and Issues of The Motor Employed in Toyota HEVs,” Proceedings of the 29th Symposium on motor technology in Techno-Frontier 2009, Session No.E-3-2, pp.E3-2-1-E3-2-20, April 2009. [12] E. Sulaiman, M. Z. Ahmad, T. Kosaka, and N. Matsui, “Design Optimization Studies on High Torque and High Power Density Hybrid Excitation Flux Switching Motor for HEV”, Procedia Engineering, Vol. 53, pp. 312–322, Mar 2013. [13] N. Naoe and T. Fukami, “Trial production of a hybrid excitation type synchronous machine,” IEEE International Electric Machines and Drives Conference, (IEMDC 2001), pp. 545-547, June 2001. [14] J. A. Tapia, F. Leonardi, T. A. Lipo, “Consequent-pole permanent-magnet machine with extended fieldweakening capability,” IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, vol. 39, no. 6 pp. 1704-1709, Dec 2003. [15] T. Kosaka, N. Matsui, “Hybrid excitation machines with powdered iron core for electrical traction drive applications,” International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems, (ICEMS 2008), pp. 2974 –2979, Oct. 2008. [16] E. Sulaiman, N. S. M. Amin, Z. A. Husin, M. Z. Ahmad, and T. Kosaka, "Design study and analysis of hybrid excitation flux switching motor with DC excitation in radial direction", IEEE Int. Power Engineering and Optimization Conference, Langkawi, June 2013. [17] E. Hoang, M. Lecrivain, and M. Gabsi, “A New Structure of a Switching Flux Synchronous Polyphased Machine with Hybrid Excitation,” Proc. of European Conference on Power Electronics and Application, (EPE-2007), Sept 2007. [18] E. Sulaiman, M. Z. Ahmad, Z. A. Haron and T. Kosaka, “Design Studies and Performance of HEFSM with Various Slot-Pole Combinations for HEV Applications”, IEEE Int. Conf. on Power and Energy (PECON-2012), Sabah, Dec 2012 [19] M. Kamiya, “Development of Traction Drive Motors for the Toyota Hybrid Systems,” IEEJ Transactions on Industrial Application, Vol.126, No.4, pp.473-479, April 2006. (in English) [20] H. Wei, C. Ming, Z. Gan, “A novel hybrid excitation fluxswitching motor for hybrid vehicles” IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, vol. 45, no.10 pp.4728–4731, Oct. 2009. [21] E. Sulaiman, T. Kosaka, N. Matsui, and M. Z. Ahmad, “Design Studies on High Torque and High Power Density HEFSM for HEV Applications”, IEEE Int. Power Eng. and Optimization Conf. (PEOCO2012), Melaka, June 2012 [22] E. Hoang, S. Hlioui, M. Lecrivain, and M. Gabsi, “Experimental Comparison of Lamination Material Case Switching Flux Synchronous Machine with Hybrid Excitation,” Proc. of European Conference on Power Electronics and Application, (EPE-2009), Sept. 2009 226