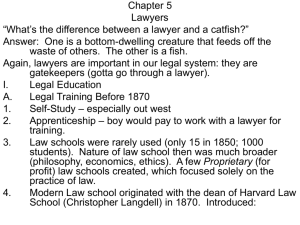

Pre-Paid and Group Legal Services

advertisement