Experiential Learning in Personal Finance: A

advertisement

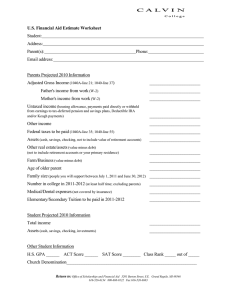

Experiential Learning in Personal Finance: A Principles and Applications Based Approach James C. Brau, Brigham Young University Jacob K. Nielson, Brigham Young University Bryan L. Sudweeks, Brigham Young University ABSTRACT This paper discusses the need for increased financial literacy among college-aged students and then presents and analyzes a personal finance class taught at a large, private university. The course is designed around five characteristics which, when combined, result in a high value-added pedagogy. These characteristics are the following: a humanistic approach to personal finance, a principles-based approach, an applications-based curriculum, a partnership with Intuit’s Quicken, and a serviceteaching requirement. With a track record of over a dozen years and 3,128 students, the course continues to be one of the best-rated courses among both students and alumni. INTRODUCTION Extant financial education and popular press literature is replete with evidence that college-age young adults are lacking in financial literacy. For example, the US government is currently facing over 1 trillion dollars in student loans outstanding (Martin & Lehren 2012). Statistically, receiving a college education remains to be a solid investment; however, nearly 66% of all Bachelor’s Degree recipients are borrowing to attend college. In 2011, the average debt for all borrowers was more than $23,000, with the top 10% owing more than $54,000 (Martin & Lehren 2012). Spiraling consumer debt, growing personal bankruptcies, low savings rates, along with the lack of retirement planning are increasingly becoming the norm. Debt has crippled college graduates and their families years after graduation, as the average American family is burdened with nearly $10,000 of loans which, in turn, is leading to bankruptcy and/or low savings. There were nearly 1.5 million chapter 7 or 13 bankruptcy filings in 2010, which analysts say will continue to grow as poor financial decisions and a weakened economy are prevalent (Mann, 2012). These types statistics have encouraged individual states to pass 24 bills, proclamations and resolutions on increasing financial literacy, and Congress to establish a Financial Literacy and Education Commission (Anthes, 2004). A vast collection of academia also recognizes the need to reform, or revolutionize, curriculum to teach students what financial literacy means, both experientially and cognitively (Anthes, 2004). As evidence that the ivory tower of higher education understands the need for personal and family financial training, many colleges and universities offer some type of personal financial planning course (Gold, Pryor & Jagolinzer 2006). These courses take on a myriad of styles and pedagogical approaches to teach students how to manage their personal finances. In this article, we continue this discussion by motivating, presenting, and critically examining one such course which has been refined Page 1 of 22 over a decade at a large private university. Financial Planning, a 400-level undergraduate course, is a principles- and applications-based approach to personal finance. It builds on the financial theory from core Finance classes and provides the opportunity to apply this knowledge to the development of each student’s personal financial plan. Dave Ramsey, a nationally syndicated radio talk show host, commented, “Personal finance is more personal than it is finance: it is more behavior than it is math” (KNBR, May 23, 2007). In this course, students learn that personal finance requires more than learning the language of finance and accounting, and more than just a change in spending habits—it requires a change in behavior. This class works to address that need to change behavior by using a principles-based approach for motivation and an applications-based approach for execution and follow-through. We do not argue that we have constructed the optimal course, and realize there may be courses at other universities that are just as good, or better, at teaching personal finance concepts. Following our intent, however, of joining the research discussion, we propose five characteristics of this specific course which may set it apart from other courses on personal finance. First, we take a potentially unique perspective on personal finance. The measure of success is not “she who dies with the most toys wins,” or “he who stands tallest when he stands on his wallet.” It is, as historian Will Durant wrote, the need “to seize the value and perspective of passing things . . . . We want to know that the little things are little, and the big things big, before it is too late; we want to see things now as they will seem forever—‘in the light of eternity’” (Durant, 1927). Our perspective is unique. It is that personal finance is not separate from our moral and ethical lives; rather, personal finance is simply part of them. Second, we take a principles-based approach to personal finance. Unlike investment theory, investment vehicles, or financial assets, principles never change. A sound understanding of the correct principles of personal finance will act as a compass to guide students as they work toward achieving their personal and family goals. Third, we take an applications-based approach to learning personal finance. We learn best when we apply the things we learn in our daily lives. It is not enough to know what to do—we must do it. Accordingly, we apply the things learned in this class in the hands-on creation of an individual Personal Financial Plan. Fourth, we have partnered with Intuit’s personal finance technology to help students reduce the time in performing personal finance. We have made Quicken 2012 Deluxe available as part of the class packet, and students learn Quicken as part of the class. The class packet includes 2 CDs: a class CD (which includes the e-book, previous semesters’ PowerPoint presentations, supplemental readings, learning tools (e.g., spreadsheets, word documents, and templates)) and Quicken 2012 Deluxe. Finally, we also take a service-teaching approach. We do not “learn to teach”; rather, we “teach to learn.” Each student is required to teach four hours of personal finance lessons of their choice to spouses, roommates, school or church groups, or any other social group and then to report on that teaching. The remainder of the paper flows as follows. First, we discuss the fifteen areas of content covered in the course. After covering each point in detail, we next discuss the three primary pedagogical delivery methods. The last section concludes. TOPICS COVERED IN THE COURSE In this section we cover the specific topics covered in the course, which prepares students stepby-step to create their Personal Financial Plan. The fifteen areas in the progression of the course are the Page 2 of 22 following: goals, personal financial statements, budget and spending plans, tax planning, cash management, credit cards, credit reports and credit scores, student/consumer loans and debt reduction, insurance planning, money and relationships, investment planning, retirement planning, estate planning, and wills. Goals Students are taught how to create short-term, medium-term, and long-term financial plans. With their Personal Financial Plan, they are then required to create three detailed, specific, and complete goals for each section, and the detailed steps needed to accomplish them. Experts relate that effective goal setting directs attention, encourages high-level performance, diminishes stress with persistence, and fosters innovation (Merritt & Berger 1998). Financial goals are obviously the core requirement, but we also encourage them to set goals in all areas of their life. Specific goals in areas such as family, physical, spiritual, and social support the success of financial goals (Ramsey 2009). Exhibit 1 is an actual example from one of our former students. Note the three areas of goals and that each of these areas have specific, attainable goals. As the ancient parable states, “Where there is no vision, the people perish,” the goals section comes first in the course project because it focuses the student on the reason behind the other 14 sections of the plan. Financial Statements After the goals section, students are then instructed on the financial statements: the balance sheet and income statement with two months of data. These students have had an introductory accounting class, so taking the step to personalize the balance sheet and income statement is very intuitive and not a big leap. At the end of this section, students calculate simple liquidity, debt, and savings ratios and provide target numbers based on their current financial situation. The students are then asked, to go back and recreate their financial statements to observe where spending needs to be cut, or savings increased, to meet their target ratios. We introduce mint.com, a personal planning website, to students for a quick visual of their current financial statues, spending habits, and other areas of development. Exhibit 2 provides an example of a student’s personal balance sheet and income statement. For the project, students report two months of projected and actual figures. Students typically track their spending either in Quicken or on Mint.com. Most students use both, as each has its specific strengths. For example, Quicken facilitates the reconciliation of accounts, such as a student’s checking account, easier. Mint does a better job at tracking and categorizing expenditures that are reported electronically (e.g., credit and debit transactions). Budgets/Spending Plans In the budgeting portion of the class, we subscribe to keeping the budget simple. The course ties our academic approach with famous practitioners so students can relate to the topics taught and see that they apply in the real world. We have previously mentioned Dave Ramsey. We also rely on the work of Suze Orman, financial advisor, television host, and author. Orman recommends a simple fivestep process for financial security (Orman, 2009). Steps 3 and 4 are creating a spending and savings plan respectively. The first step within this area is to create an itemized list of wants and needs based off the student’s expenses for the current month. Using financial software, like Quicken, they are easily able to forecast spending reports a year out. The teaching point in the budgets and spending exercises Page 3 of 22 is to show what the student is doing well, what he or she needs to improve and the action plan to help him or her balance the personal budget. Exhibit 3 illustrates a sample budget from a course project. The course stresses to pay humanity first (e.g., charity, church, etc.), and self second (i.e., savings). This order of payment follows the principle-based approach of the class. As students begin to understand that they have an obligation to help their fellow person, and that they need to prepare for their own future before satisfying their immediate wants, and perhaps perceived needs, they will live a more fulfilled life. Tax Planning Although undergraduate students are unable to implement advanced tax strategy, we teach effective Federal and state forms to increase this important area of financial literacy. We also cover areas for future use including the following: capital gains taxes, deferred tax methods, educational savings vehicles, and tax credits. A key element to this section of the curriculum is having students grasp the magnitude that tax planning will have on their achievement of personal goals. Taxes are the largest single expense for most people; most individuals and families work four or more months just to pay their taxes each year (Anthes, 2004). Students are introduced to deductions which they may not be aware, in particular, deductions for charitable mileage, business mileage, and moving or medical mileage expense deductions. In 2012, the deductions range from $0.14 to $0.55 per mile driven. Other tax issues we teach students about are designed to help them while they are students. For example, the Earned Income Tax Credit, American Opportunity Tax Credit, Lifetime Learning Credit, and Tuition and Fees Deduction have the potential to contemporaneously apply to students in the class. We teach our students to be honest and upright in all financial endeavors, but the less they (legally) pay in their tax burden, the more they will have for their personal and financial goals created during the course. Cash Management The course learning objective for this area is for students to understand the importance of good cash management and how it can help them achieve their goals. Secondary objectives include developing an understanding of the different types of financial institutions, and how to compare them, and the need to spend time weekly to update and track personal finances. Students learn that being able to calculate and understand current rates and costs of savings and checking facilitate added financial freedom in the upcoming years with greater flexibility for investment opportunities. Students learn to integrate the class budgeting and spending section with the cash management section. For example, the course strongly advocates the best investments one can make in school are to first, pay off all debts and second, creating a liquid asset account to cover at least six months of expenses. Students learn that there are a wide range of alternatives, each with unique benefits and costs, in the field of cash management. As such, the following areas are covered in this section: checking accounts, savings accounts, money market accounts, Money Market Mutual Funds, certificates of deposit, U.S. Treasury bills, and U.S. Savings bonds. The concepts of money vehicles are important as we then move to helping them compare the various options and choose which vehicle best fits their financial needs. We teach students to compare by interest rates (APY and APR), calculate returns after tax, calculate the returns after inflation, risk consideration, maturity terms, and interest rate adjustment periods. With so many alternatives and options in the industry today, it is imperative students not only Page 4 of 22 understand that one vehicle may be financially better than another, but they know how to determine the optimal plan. Credit Cards The availability of credit cards among college students, who on average have four, has raised concerns over the misuses and consequences, both short and long-term (Robb, 2011). Using a sample of 1,354 students, Robb (2011) suggests financial knowledge plays a significant factor in the credit card decisions of college students. Many college students are uninformed, or blatantly ignore the negative consequences of high credit card debt. These negative effects include, but are not limited to, a low credit score, a higher interest rate on future loans, harder to get approved for an auto loan or house mortgage, and higher insurance premiums. We teach students that there are reputable credit card companies and banks that offer credit cards specifically designed for college students, with lower interest rates and smaller spending limits. We present the current options in the credit market with the cards the students hold individually. By teaching students to analyze the key areas of interest rates, fee structures, cash advance costs, and credit limit per card, students can clearly see which cards are most beneficial. Students learn that selecting the “right” card is a start towards limiting the average consumer debt students are burdened with. Exhibit 4 is an example of the various credit cards currently either being marketed to college students, or those being owned by the students. Relative data such as the Annual Percentage Rate, annual fee structures, and credit limits are shown for numerous cards. Credit Reports and Credit Score By using a credit card rationally, students are able to get added benefits such as points, cash back, and a higher credit score. Students learn that credit scores have specific factors (e.g., annual income, age, employment status, number of credit cards, history) that equal one aggregate total sore. As briefly described previously, the higher the credit score, the lower the interest rates for most future loans and insurance premiums. Students learn that improving credit strategy can have a tremendous impact on their finances as college students, and after. Credit cards can be used for emergencies, convenience when buying over the internet, buying items that are on sale before a paycheck, or with free services. The challenge educators face is translating the knowledge learned in the classroom to practical use in real life— students must absolutely be taught that they should pay the credit card off entirely each month unless in emergencies. Of course, the definition of an emergency to a college student may be his or her next hot date. Exhibit 5 is a selection from the credit report of a former student’s course project. Students download their credit reports from annualcreditreport.com and analyze them as taught in class. They are taught to look for errors in the report and taught how to correct them if they exist. In our experience, the credit report is a wake-up call for students, especially those who have been late on paying bills that have been reported. Student/Consumer Loans and Debt Reduction Page 5 of 22 One trillion dollars in student debt outstanding is what the Federal government currently deals with (Martin and Lehren, 2012). As educators and personal finance experts, we are always looking for new methodologies, techniques, and practices to teach those who attend our classes to be better equipped financially. With the rising cost of education, students are seeking lenders, whether governmental or commercial, to help with their expenses and allow them to continue their education. With a fundamental assumption that education is the best investment a young person can make, this course attempts to teach a debt reduction strategy so it will be more than a right answer on a Scantron. The average college student graduates with more than $25,000 of student loan debt (Martin & Lehren 2012). In order to begin paying this off and other debt, we have, in the broadest sense, categorized the solutions into three categories. The first is the personal strategy. Making a list based on the financial statements the students created, we can readily read which debts have the highest interest rates; they can create short term plans to begin to pay those in an easy-to-understand debt-reduction system (Ashton, 1992). The next category of debt reduction the students learn about is counseling agencies. They learn these agencies should only be used if students are too far in debt to successfully use the simple debtreduction strategy used in class. The last option students learn pertaining to debt reduction is legal action, i.e., declaring bankruptcy. We teach that bankruptcy should almost always be the last solution and hope students never need to pursue this corrective measure, but accidents happen and occasions permit such drastic solutions. Students learn that 89% of all bankruptcies are due to three events: divorce or death, unpaid medical expenses, and the loss of primary employment (Ashton, 1992). The course stresses that if students eliminate the likelihood of these events then they can reduce substantially their chance of filing bankruptcy. Insurance Planning Most universities provide healthcare plans for the student body and faculty at a reduced cost, in comparison to plans in the current marketplace. The student insurance covers most, if not all, illness and accident coverage, outpatient therapy, and maternity care with an 80/20 split after copayment. As many college students are under the burden of debt, it is not practical or advisable for them to purchase permanent or term insurance, unless they are married or with dependents. In these cases, it is strong recommended. We teach after student loans have been repaid, life insurance should be the next purchase. Students learn that insurance premiums dramatically increase as one ages and it is wise to become insured early generally in level-term life insurance. The course teaches that other insurance products students need to consider are auto, renters, home, and disability. Many do not currently have the need for all of these insurance products; nonetheless, within the upcoming years the need will arise, and educating students and having them create their life plans has proven beneficial. Exhibit 6 demonstrates the use of the life insurance template provided as one of the tools in the class. The indications of life insurance needs, based off of six different approaches, are presented. With the averages calculated, this individual example gives monetary values for projected values and averages to meet the needs for their family. Money and Relationships A key indicator of financial literacy is the communication bridge between husband and wife, as well as between parents and children. We strongly value the in-home teaching that has been done Page 6 of 22 before and look to expand upon it as spouses and parents have a significant impact on young adults’ personal financial knowledge, attitudes and behavior (Jorgensen & Savla, 2010). The correlation between behavior of parents who not only understand their personal finances but also regularly contribute to their Individual Retirement Accounts and Defined Contribution Accounts, both directly and indirectly, impact their households’ attitudes and behavior. This type of money relationship we look to expand going forward, so our students will be able to successfully teach the rising generations about best practice of financial responsibility and personal finance planning. Investment Planning This Investment Plan (also called an investment policy statement or IPS) serves as the framework for the Investment Management section of the Personal Finance Course. The Plan acknowledges the expected risk and return along with market volatility, and constraints of the evaluation and modifications that occur. This plan supposes two distinct time frames from which to view the student’s investment objectives. Stage 1 is between now and the student’s 55th birthday (this is an arbitrary date set by the student) and is expected to last 30 years. It is generally considered the time before retirement. During this stage, the student’s primary objective is current income, conservative growth, growth, and aggressive growth. Stage 2 is between the student’s 56th and 91st birthday, and is expected to also last 30 years. It is generally considered the period during retirement. During this stage, the student’s primary objective will be capital preservation, current income, growth and income, and growth. The Investment Plan proposes the creation and use of multiple sub-accounts. These include taxable accounts, such as multiple taxable investment accounts, retirement accounts, (401Ks, IRA, Roth IRAs, SEP IRA/SIMPLE Plans), education accounts (Education IRA, college 529 Savings Plan), and taxable investment accounts. Retirement and education accounts and goals are also discussed in great detail. With these plans prepared by students that are presented to the class, students begin to develop a true understanding and sense of urgency for the place for proper investment. Exhibit 7 illustrates the return objective simulation template which is provided to, and explained to, the students. The return objective simulation has six areas of personal investment strategy with appropriate weight that individuals assign within their portfolio. With the personal investment strategy, Exhibit 7 shows how this student allocated weights and forecasted expected returns. Retirement Planning The retirement planning section, very much like the investment planning material, is designed for students to create goals and to formulate a retirement plan. Economists are now beginning to show how the lack of financial literacy is affecting retirement, where now the consequences are more present than ever. A majority of households within the United States are arriving close to retirement with little or no wealth. The current study reflects those households are unfamiliar with even the most basic economic concepts needed for investment and saving decision. As one generation demonstrates woeful financial illiteracy, government and academic institutions undertake preventative measure to correct trends (West 2012). Naturally there is more than one path to the top of a mountain. As with hiking, there are many different methods and retirement planning strategies to achieve desired goals. We focus on the Individual Retirement Accounts (i.e., traditional IRAs) and Roth IRAs in this section heavily, as it has gained wide acceptance among college students and financial advisors. The Roth IRA becomes the Page 7 of 22 preferred tool, in comparison to the traditional IRA and mutual funds, as the tax rate at contribution will assumedly be lower than at retirement (Adelman & Cross 2005). These plans will help serve as a first stepping stone as they move from college to career and we hope they will impact their financial future better than existing data is suggesting about the current generation. Exhibit 8 illustrates the course teaching tool template to help students compute the amount of retirement funds they will need. Projections and estimates are made in this student’s example with forecasted annual earnings, and social security contributions. The model also takes into account the rate of inflation when planning to retire as shown. Estate Planning Towards the end of the course, students learn how to develop an estate planning strategy. During this phase, it is often useful to have a guest speaker who specializes in estate planning to give a lecture. We have found that when an estate attorney presents, the students become very engaged. War stories from the guest speakers are of particular interest. Because college students are typically faraway from retirement and estate planning, these topics are taught in a manner to impress upon them their subsequent importance in their life-time planning process. Wills During the estate planning lecture, it is also effective to have the guest speaker discuss the importance of wills, and especially living wills and powers of attorney. Students learn that even if they are single, it is important for them to have their affairs in order. Students are shown basic wills and they complete them for the class. We have found that students who have a will in college tend to update the will as they get married and progress through life. We use the sad case of Terri Schiavo, a lady who did not have any medical directives, as an illustration of why it is important for young people to have their living wills and medical affairs in order. PEDAGOGICAL DELIVERY METHODS The course uses multiple delivery methods to enhance student learning. All of the material developed is available to the public for free at the course webpage. This page, http://personalfinance.byu.edu, was developed by the course author and is updated and improved each year. Every section was peer-reviewed by a member of the finance faculty when the page was originally posted. The website has had close to a half-million hits over the past 8 years. The website has three primary areas of content: personal finance manuals, PowerPoint presentations, and a large section of learning tools. Below, we discuss the key features of each of these areas. Free Personal Finance Manuals The 600-page book used in this class and eight other books are freely available for download and are updated each year. The 2012–2013 editions are available online. These Personal Finance Manuals cover finance topics such as: High School, Freshman College, Returned Missionary, Complete College, Young Married/ Single Adult, Intermediate Investing, Advanced Investing, and Retirement Planning. Page 8 of 22 The High School Personal Finance Manual covers material relevant for high school students as they are approaching graduation. Understanding wealth with a new perspective, creating financial plans and setting personal goals, as well as understanding consumer credit and debt are all chapters geared towards boosting literacy to those in high school. Building upon a solid foundation from the high school manual, we have written specifically for incoming freshman. We take a deeper look into managing credit and debt reduction strategies along with added principles that are more dynamic and complex. We briefly cover topics in Consumer and mortgage loans, time value of money, inflation, annuities and real returns. Being a private academic institute, a majority of our students are a bit older as they have been serving in various positions in geographic locations that span the globe. We have designed a manual as they transition back into college, as many of them have started classes but have taken a leave for a few years. Like previous books, we delve into deeper meaning of the basics while adding only one new section, the basics of health and life insurance. The comprehensive college manual is aimed for students to know much more than the basic high school manual. It also is compiled with concepts which are more difficult, like tax planning, cash management, and present and future value of money. This serves as a great quick-reference guide in areas from insurance to retirement planning for those moving from college to professional careers. The manual for newly married students takes into account that finance is now a team sport within the home. Being single and making financial decisions had an impact on a sole person; however, now with a spouse also being affected, proper planning is a must. These plans include items such as auto insurance, disability insurance, planning for children and their education, as well as communication techniques. Transitioning away from the basics of personal finance, the intermediate investment manual covers the six factors that control investment return as well as the ten principles of successful investing. This is a great guide for those who want to solidify their basic knowledge of investments without delving too deeply into the complex. After the basics presented in the intermediate investment manual are learned, the progression to advanced investing should be a bit easier. As the title indicates, this is for advanced and serious investors who are interested in security markets, bonds, stocks, mutual funds, and diversification of personal portfolios. The final manual that is offered is for retirement planning. The more common retirement plans (i.e., Employee Qualified Plans, Defined-Benefit Plans, Defined-Contribution Plans, Individual and Small Business Plans, and Estate Planning) are all discussed and presented. With this guide, students, and anyone else who reads it, should be able to make informed and educated decisions on what meets their individual and family’s needs. We encourage all to read and to seriously contemplate how to better be financially situated for their individual retirements. PowerPoint Presentations PowerPoint presentations used in this class, daily class summaries, and quiz reviews are available online. PowerPoints are available generally the day before they are presented in class. The PowerPoint library for the course is extensive and is an integral part of an online version of the course which is offered free to the public. Learning Tools Page 9 of 22 Learning tools which are used to help teach the class and help students in various areas are available online. They include tools to help in the areas of debt reduction, budgeting, insurance, investing, taxes, retirement planning, auto buying, and home buying. These spreadsheets and word documents are updated periodically and are available on the website. Some of the exhibits previously discuss are examples of these teaching tools. CONCLUSION Academics and practitioners alike agree that there is a need for personal finance education among young people. In this paper, we examine one possible approach to filling this need. Using a combination of principle- and application-based pedagogy, we present a path for teaching students how to create their own personal financial plan. Student reception of this approach over the past 12 years and over 3,000 students is very positive. The semester-long undergraduate course covers fifteen subject areas: goals, personal financial statements, budget and spending plans, tax planning, cash management, credit cards, credit reports and credit scores, student/consumer loans and debt reduction, insurance planning, money and relationships, investment planning, retirement planning, estate planning, and wills. By teaching both the why and the how, we argue that this course, or a similar course, has the potential to add significant value for college-aged students. Page 10 of 22 Exhibit 1: An Example of Student Goals Page 11 of 22 Page 12 of 22 Page 13 of 22 Exhibit 2: An Example of a Student’s Personal Financial Statements Page 14 of 22 Page 15 of 22 Exhibit 3: An Example of a Student’s Personal Budget Page 16 of 22 Exhibit 4: An Example of a Student’s Credit Card Analysis Page 17 of 22 Exhibit 5: An Example of a Student’s Credit Report Page 18 of 22 Exhibit 6: An Example of a Student’s Life Insurance Needs Template Page 19 of 22 Exhibit 7: An Example of a Student’s Expected Return Teaching Tool Page 20 of 22 Exhibit 8: An Example of a Student’s Retirement Needs Teaching Tool Page 21 of 22 REFERENCES Adelman, S. W., & Cross, M. L. (2005). Use of Roth IRAs by young college graduates for retirement planning purposes. Pensions: An International Journal, 11(1), 47-51. Anthes, W. L. (2004). Financial illiteracy in America: A perfect storm, a perfect opportunity. Journal of Financial Service Professionals, 58(6), 49-57. Ashton, Marvin J. (2006). One for the Money: Guide To Family Finance, Salt Lake City, LDS. Durrant, Will (1927). The Story of Philosophy, New York: Simon and Schuster. Gold, J., Pryor, C., & Jagolinzer, P. (2006). A study of for-credit introductory personal financial planning courses. Financial Services Review, 15(2), 167-179. Jorgensen, B. L., & Savla, J. (2010). Financial literacy of young adults: The importance of parental socialization. Family Relations, 59(4), 465-478. Martin, A. & Lehren, A.L (2012, May 12). A generation hobbled by the soaring cost of college. Degrees of Debt. Merritt, E. A., & Berger, F. (1998). The value of setting goals. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 39(1), 40-49. Orman, S. (2009, January 15). Suze Orman’s 5-Step Financial Action Plan. Retrieved August 24, 2012. Ramsey, D. (2009, July 20). Life and Money-Goal Setting. Goal Setting’s Big Payoff. Retrieved August 24, 2012. Robb, C. A. (2011). Financial knowledge and credit card behavior of college students. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(4), 690-698. West, J. (2012). Financial advisor participation rates and low net worth investors. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 17(1), 50-66. doi: 10.1057/fsm.2012.4 Page 22 of 22