martha morgan history

advertisement

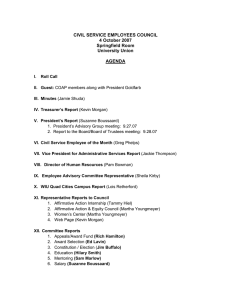

Martha Morgan: A Journey to Zion by Alan Morgan Kendall In the little town of Levan, Utah stands a log cabin, a rustic and weathered monument to a few who transformed a field of grass near a mountain stream into a home. Sheltered in those aging walls are the artifacts of toil which sustained them. Pictured on the walls are those pioneers whose shoulders bore the burden of that toil. It was they who broke the first soil, laid the first adobe, gave birth to and nurtured the first child. One such photograph reveals an elderly woman, sitting attentively in a high backed chair, her smooth and kindly face framed tightly by a black bonnet. Her dress is Victorian black, long sleeves covering even her wrists, with a large bow modestly gathered at her neck. In her lap she holds a thin cloth bound volume, one matronly finger marking a place, as if the photographer had interrupted a quiet moment with the poetry of Robert Burns. Her hands are thick, showing the strength of many years of labor. She gazes placidly, as she has for decades, with just a hint of a smile. Her name is Martha Morgan, and this is her story. Unfortunately, Martha and her kin never left a written record. We will not know for now what was happening behind that gentle smile, or why she and her family made decisions as they did. But in their journey across an ocean, and into a strange new land they left their imprints, and they collectively tell a story, truly, a journey to a Zion after which they faithfully sought. Her birth in Scotland She was actually christened Matilda Neilson in the old parish church of Inveresk, Midlothian County on 19 December 1824. She was exactly one month old.1 How she became a Martha is unknown. Martha Matilda is a common female name combination, probably popular from it's lilting sound, and maybe was used informally, and, as such names do, just stuck. McGill is another name sometimes fastened to her, that would have been handed to her by a paternal grandmother whose maiden name it was. Her maiden name also evolved over the years. It was frequently shortened to Nelson by brothers who came to America, and even some records in Scotland show the shortened version. Inveresk Parish Church Martha, as we shall call her, was the daughter of Edward Neilson and his wife Catherine Banks, the sixth of eight children.2 The Neilsons were a family of coal miners and had been for as many generations as records exist.3 Which meant, for those in the 19th and prior centuries in Scotland, they were to inherit this grim legacy: They would work very hard in a harsh environment, raise a large family, and likely die young. The Coal Miners In her book Coal: A Human History, author Barbara Freese makes this wry comment: “In one respect, the seventeenth century English coal miner was lucky; At least he wasn't a coal miner in Scotland.” 4 It was an occupation that was already hazardous and strenuous, but the Scots took it one step further. They made it a sort of legal servitude as well, probably because of it's difficulty. In the early 17th century legislation had been passed in Scotland that made the “colliers” virtually the property of the owners of the coal mines. Without the owners permission they were legally forbidden to leave the mine for other employment. The owners were free to impose cruel and humiliating punishments upon anyone violating their will. They could press into their service any vagrant or person not otherwise engaged in labor. It was a common practice to secure the labor of children in a family by the payment of a small bounty to the parents, thus securing yet another generation under their control. Socially, colliers and their families were ostracized, and their children were not allowed to attend school, even if they had the time apart from their labors in the mines. They were normally worked 6 very long days per week, with the Sabbath day off and one annual holiday, Christmas Day. Conditions improved with more humane laws being passed by 1800, but children were still being forced to labor under these hazardous conditions until 1841. Martha herself may have worked in the mines as a child with her mother and siblings to help support her family. While women and children were not required to work at the mine face, their primary duty was to haul out the coal, pushing trams or carrying it on their backs. It was still difficult and dangerous work, under which the Neilson families had chafed for many generations. The Neilsons and their forebears had lived in various “collier villages” south and east of Edinburgh for many years, moving as required by the mine owners or in later years, in order to secure employment.5 Even in the enlightened 19th century the wealthy coal magnates were still shrewd in manipulating those in their employ. Her Childhood Little can be said of her childhood, except for the possibility of employment in the coal mines. Did Martha attend school? Education was highly regarded among the Scottish people, and each parish was required to have a school. But not all children attended the schools. Martha may have missed the opportunity due to her status in a collier family. A gauge of her education would be in her ability to read and write. According to the 1850 U. S. census she could do neither. By 1860 it was reported that she could, while the 1870 census says she could read but not write. Both 1880 and 1900 census records give her a passing grade in literacy. It appears that she may have learned later in life. If so, that would be a high accomplishment for a busy frontier wife and mother. However, in her later years she lived among a people who also placed education as a high priority. Before her 17th birthday, her family had moved from Inveresk far west to the outskirts of the Glasgow area. They lived in an area known as New Dundyvan in North Lanarkshire6, a polluted and gritty industrial center outside of the city. It was a center of coal mining and iron manufacture, and so drew the likes of the Neilson family to pursue their livelihood. It also attracted, as divine destiny would have it, the family of Martha's future husband. -2- Her Marriage Daniel Morgan and his wife Agnes Beveridge were also descended from many generations of coal miners. They and their children, too, were drawn to this coal and iron center, pulsing with an intensity fueled by the industrial revolution in full swing. And so it was that the children of colliers perpetuated their race. Their son William Morgan was nearly 24 years old when he asked young Martha “Nelson” , a tender 16 year old, to be his wife. On 13 Mar 1841 at the Old Monkland parish of the Church of Scotland (Presbyterian), William and Martha presented their names for the reading of banns announcing their intention to marry.7 The reading of banns was a practice by which the announcement of their impending marriage was made at three successive services, and was usually done in lieu of a marriage license. By the time the 1841 Scotland census was taken on 6 June 1841, William and Martha had been married.8 Life in New Dundyvan The new Morgan family had parents and siblings in the area, all coal miners or iron workers. They seemed to be a close knit group. “Close” may be a word to describe their living conditions in a less than desirable way, for most of the miners lived in row houses, owned, of course, by the coal mines. The row houses were crowded and notoriously unsanitary. Typical Row Houses in a Collier Village These years were a season of unrest in the corridor between the major Scottish cities of Glasgow and Edinburgh. The laboring populace seemed to be seeking for something better, and it was manifested, as it commonly is, in bitter feelings between the working class and the managing owners. One noteworthy rebellion occurred in December 1842 at the Dundyvan works. The coalminers united and went on strike for improvements. In response, the owners simply put the strikers out of their row houses into the streets at the mercy of the local charities. The strike was soon settled.9 Fortunately, the Morgans and kin had moved on by this time, but they must have received the news with keen interest. Life in Dunfermline Dunfermline is an ancient city perched high over the Firth of Forth, the inlet of the North Sea entering Scotland. It was a center of royalty anciently, went into decline and decay, and was revived to respectability by the industrial revolution. It was, among other things, an iron foundry town, and that meant the need for coal. It was coal that was the life of the predecessors of William Morgan, as we have learned, not necessarily by their choice. William and Martha, as well as members of the Nelson family relocated to Dunfermline shortly after their marriage. That is where their first child was born in the village of Hallbeath on 27 May 1842. The little girl was named Catherine Banks Morgan, after Martha's mother. Their family continued to grow as they lived and worked in the Dunfermline area, moving from village to village as opportunities arose. Son Daniel (named for William's father) was born in Hallbeath 16 July 1844, followed by Agnes Beveridge (for William's mother) on 20 Aug 1846.10 -3- The honorary naming of the children, plus the migration habits of the Morgans and Nelsons show strong family ties, which were to continue throughout their lives. As was mentioned this was a decade of change and some strife in Scotland. Thinking men and women could not help but consider the inequalities existing among the classes in their society. The sense of injustice must have been particularly keen to the Morgans, whose family had been under the stigma of their occupation for generations, and who probably suffered it firsthand. They may have wondered how, in a Christian nation, the prevailing church had been unable, or unwilling, to produce a society in which brotherly love produced a greater degree of justice. If they had considered, and even prayed for an answer to such a question, it was about to come forth. A New Religion Shortly after it's founding in the United States, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints sent missionaries worldwide, with particular interest in the United Kingdom. Apostle Orson Pratt was sent to preside over the mission there, and early in 1840 climbed to the mountain peak of Arthur's Seat in Edinburgh to dedicate Scotland to the preaching of the restored gospel. It was a prophetic act, and converts to “Mormonism”, as the new religion became known, multiplied rapidly. For the Morgan and Nelson families, hearing the proclamation of a new order of things based truly upon ancient biblical principles must have been a welcome source of hope. Over a period of four years many family members entered into the waters of baptism, and became members of the new Dunfermline Branch of the church. The first was Martha's brother John in July 1846 followed by William's older brother David in September. William was next on the first day of 1847. The siblings followed, Thomas Morgan and Edward Banks Nelson on 1 June. About a week later Martha was baptized on the same day as her older sister Jane McGill Nelson Morgan, whom, it is believed, was married to a brother of William. Through 1850, Ninian Nelson, Janet Morgan, Jane Morgan, Agnes Ann Morgan, and William's mother Agnes Beveridge Morgan also joined the church. Apostle Orson Pratt must have personally ministered to the Saints in Dunfermline, it was he who confirmed Agnes Morgan a member of the church.11 In 1849 the families moved to the village and branch of Oakley, a collier town to the west of Dunfermline, where John Nelson served as the branch president.12 Persecution followed, but William and Martha were anxiously engaged in the work of the gospel in the Oakley Branch. William received the priesthood and exercised it to the blessing of others. Of course, their desire was to join the central body of the saints in America. Not all of the family emigrated, however. David Morgan and his wife Grace emigrated to America in 1852. Edward and Agnes Morgan Banks left about 1862 and settled in New Mexico. Janet Morgan eventually settled in Northern California where she died in 1908. John Nelson settled in the Logan, Utah area and brother Ninian just to the north in Dayton, Idaho.13 For the William Morgan family, the desire began to be realized when William registered with the church emigration service in July 1849.14 Martha's journey to Zion was about to begin. For the long voyage she would care for four children under the age of 8 years. Fortunately, she -4- would have the help of a dear older sister, Jane McGill Nelson Morgan15, now a widow. Martha and Jane must have had a close relationship, judging from the many parallels in their lives. The Journey to America The Morgan's traveled from Scotland to Liverpool, England in August to begin their sea voyage. Their passage was actually paid by James Watson, an agent of the Church16. Some have assumed this to be through the Perpetual Emigration Fund, but that program did not begin for another month. Either way, it seems that the Morgans received some assistance on their ticket, which may explain their future delay in arriving in Utah. William was probably resolved to work off an obligation before proceeding to the valley. In Liverpool, the Music Hall had been rented to receive the passengers until their ship was ready, so the family may have stayed there for a time, making final preparations and last minute purchases. On the first of September they boarded the James Pennell, the sailing ship that would take them across the Atlantic Ocean. There were 250 LDS passengers, about half of them from Scotland. One can imagine the busyness of preparing to get underway. William was probably engaged in lashing down their trunks while Martha and Jane were preparing the bunks or cooking. How wonderful and strange this must have seemed to the children. Journals of the trip describe a spirit of harmony among the saints, all working together for a common good. On the morning of 2 September the James Pennell was tugged down the Mersey River to the Irish Sea as nearly all the ships company was on deck, singing hymns. It must have been a bittersweet farewell to their native land. On the third day, they had cleared the coast of Ireland and were into the open sea, which meant the rolling and shifting of the vessel bringing on the agony of sea sickness. The passenger's journals described the captain of the ship to be exceptionally considerate of his passengers, and he successfully made efforts to provide a pleasant journey to those in his stewardship. This was very fortunate, for they were underway for over 6 weeks. There was a violinist and accordionist on board as well as singers, so entertainment was available. The only cause for sorrow was the death of two sick babies. They also received a bit of a fright during a storm in the Gulf of Mexico, during which the top mizzen mast was broken off. On the evening of 20 October, a steam tugboat fastened to the James Pennell and pulled her into the mouth of the Mississippi River. The Morgans were probably up past midnight watching as the ship entered this great river, and likely up at dawn the next morning, standing on the quarter deck to get a better view of the strange plantations bordering either side of the river. They reached New Orleans on the 22nd, and tied up to the levee. They were in America!17 After they disembarked, rental houses were provided for some, but most continued by steamboat up the Mississippi to St. Louis, Missouri. On the way up the river the Morgans may have discovered that coal mining was common in nearby Jackson County, Illinois. Jane Morgan stayed in St. Louis with the Saints waiting to cross the plains, while William and Martha and the children returned about 60 miles to the south, where William obtained work in the coal mines there. He was earning money to get outfitted for the overland journey to Salt Lake City, and probably to honorably settle the debt for passage over the Atlantic. A year later, the 1850 -5- census shows the Morgans to still be living in the south district of Jackson County, with William working as a miner.18 The sweltering Mississippi River summer of 1850 must have been a new experience for Martha and the children. They may have missed the cool Scottish weather. Crossing the Plains The names of the Morgan family don't appear on any of the known rosters of pioneer companies crossing the plains, so we can only speculate on when and how they made the trek. It does seem reasonable, however, that they would have stayed close to sister Jane for the crossing. Jane Morgan met and married another Scottish immigrant while staying in St. Louis. Her new husband was recently widowed Andrew Patterson. They had undoubtedly known each other in Scotland, as Andrew had been a member of the Dunfermline branch. They had made their way to Council Bluffs, Iowa by May 1852, for their first child was born there19. It seems very likely, then, that they all made the crossing in the summer of 1852.20 A William Morgan appears twice on the Annual Bishop's report of 1852. One, possibly this William, in the Salt Lake 15th Ward, and another, very likely our subject, in the Nephi Ward.21 This suggests the scenario of the Morgans stopping briefly in Salt Lake City, with William laboring for public works temporarily to completely discharge the emigration debt, and then being called to strengthen the new settlement at Salt Creek, soon to be called Nephi.22 Jane Patterson and Andrew, an iron miner, were called directly to the Iron Mission in Cedar City. Their paths would cross again soon. Life in Nephi The first settlers came to Salt Creek in October 1851, so when the Morgans arrived the next year, things were still just getting started. William and Martha left few records of their time in Nephi. One can be sure that they were more concerned with surviving than with leaving a history of it. William was now challenged with becoming a farmer rather than a miner. Fortunately, he had some experience of working in the fields as a youth, but it must have been, none the less, a learning experience for the entire family. A sad reminder of their stay in Nephi is a tiny grave. Martha gave birth to a daughter, Mary Ann Elizabeth in 1853, but she lived for only just over a year.23 Their sadness must have been offset by being involved and working cooperatively with the Saints in Nephi. It was now not only what they had sought for in leaving their native land, but necessary for their survival. They received further comfort and reassurance in August of 1854 when William Cazier laid hands upon them and pronounced a patriarchal blessing, declaring them to be descended from the noble tribe of Joseph, and revealing other aspect of God's will that would comfort them in their journey yet to come. Both William and Martha received their blessings at this time, as well as their older children Catherine, 12, and Daniel, 10.24 -6- Sacred Covenants The sacred endowment and the marriage sealing were the pinnacle of the eternal ordinances offered to the Latter-day Saints. Upon their arrival in the Salt Lake valley, the vanguard of pioneers under the direction of Brigham Young began making preparations for the building of a temple for these holy purposes. As the completion of this or any temple was still years in the future, a means was provided for church members to receive the endowment. It was the Endowment House, built on what is now temple square in Salt Lake City. The Endowment House It appears that William and Martha were anxiously engaged in the work of the Kingdom, and also anxious to receive their ordinances. The Endowment House was opened in 1855, and they made the journey to Salt Lake City in September of that year. That was a trip of 90 miles and probably took 4-5 days to complete. Travelers in those days frequently stayed with family or friends in the evenly spaced settlements along the Wasatch front. Significantly, they were joined by Andrew and Jane Patterson for the trip, who must have traveled all the way from Cedar City, an even lengthier journey. And so it was that the four of them and about twenty others, spent the day on 4 September 1855 in the endowment house, for it was an all day experience in those times. Among those administering the endowment were such luminaries as Heber C. Kimball, W. W. Phelps, and Eliza R. Snow. Another present who probably remembered the Morgans from his days in Scotland was Apostle Orson Pratt. At the conclusion of the day at 4 pm, as the sun hung low over the Oquihhr Mountains, William and Martha knelt at an altar in the endowment house and were sealed as husband and wife for eternity by Pres. Kimball. J. W. Cummings and W. W. Phelps acted as witnesses.25 Martha Morgan William Morgan -7- The Iron Mission The trip to Salt Lake City may have begun more than the eternal continuation of their marriage. To understand this, we must understand the Iron Mission. When Apostle Parley Pratt led exploration far to the south of Salt Lake valley one of the important discoveries made was that of iron ore. It provided an exciting potential resource to a people striving to become independent of the iron products being shipped at dear prices from the east. In 1851 a company of pioneers were sent to what was then called Little Salt Lake Valley, 250 miles from Salt Lake proper with the specific mission to establish an iron industry for the support of settlements in the Great Basin and surrounding areas. The initial settlement was Parowan, but the iron works were set up 20 miles to the southwest. A fort was built there called Fort Cedar, and it grew into the town of Cedar City. It was selected because of coal to the east and iron ore to the west. The mission struggled valiantly from the beginning. Between snow and ice, drought, Indian attacks, and poor quality coal, the production of usable iron seemed nearly out of reach. But they persisted for years. As late as June 1855, Pres. Brigham Young was still calling for experienced European iron workers to go to the Little Salt Lake Valley.26 This may have prompted the Morgans to move there. During their visit to Salt Lake City William may have received a call to serve in the coal mining operation when Elder Pratt and others were reminded of his experience. Or he may have been persuaded by brother in law Andrew Patterson, who was already serving there. One thing is certain, there was little personal advantage to their family. They were probably looking forward to settling permanently in Nephi with the dream of a little farm of their own at the base of majestic Mount Nebo. The move to Cedar City was a call to duty, a faithful response to the consideration of the sacred covenants they had just made. The Morgans were in Cedar City by 1856. Their presence there was again marked by the birth and death of another child. Thomas William Morgan, less than 6 months old, died there on 20 September 1856.27 Although conditions in the iron works had improved since the beginning, in which workers were clothed in rags and sometimes shoeless, these were still difficult years. Payment for workers was made in kind through the store of the Deseret Iron Company, and requisitioned payments usually exceeded store inventory. Coal Creek flooded frequently and inundated the iron works. Drought and grasshopper infestation in 1856 began a serious decline in the operation. The Utah War in 1857 sounded the death knell for the iron works with its disruption and draw upon resources. The tension in the area was further increased by the Mountain Meadows Massacre in September of 1857. The operation finally closed in 1858.28 From a practical perspective, the Iron Mission was a failure. But for the Morgan family and the others who sacrificed greatly in this effort much more than iron was produced in the fiery furnace which burned there. Once again the character of the saints who gave much was forged to a more perfect form in a test which could have made them or broken them. The cooperative op-8- eration of the church functioned throughout their time there. In 1856 a Female Benevolent Society (Relief Society) was organized in Cedar City. Martha Morgan would have been a part of it. Martha gave birth to a healthy son there, on 1 Oct 1857, and named him in honor of her father Edward Nelson Morgan.29 Life in Beaver As the impracticality of iron production at Cedar City became more apparent, the population decreased sharply. There were about 1000 residents in 1855, but by 1860 only about 400 remained. Among those leaving were the Andrew and Jane Patterson family. Early in 1856 they were among the first of the settlers moving 36 miles to the north to a location on the Beaver River.30 When the Morgans left as the iron works closed, they joined the Pattersons in Beaver. As the 1860 census was taken William was listed, no longer as a miner, but as a farmer. Also on this census William and Martha possessed something that would probably have never been theirs if they had remained in Scotland: $350 in real property.31 Here Martha gave birth to another son on 22 January 1860. She named him John Athos Morgan.32 The middle name given to the lad is interesting. Not a family name, it makes one wonder if Martha had developed a literary interest. Athos, of course, was the name of one of the fictional Three Musketeers in Alexander Dumas' 1844 novel of that title. Perhaps the book she was holding in her elderly portrait was more than a prop, but an icon of her interests to those of a later generation Beaver was a beautiful location, hunting and other natural resources were abundant. The settlement was growing rapidly, ironically, due to the Utah War. Pres. Young had called many church members who were living in the corridor between there and San Bernardino, California back into the Utah Territory. Many of them found Beaver a desirable place to live. The Morgans apparently found it desirable to move on. Chicken Creek and Levan Chicken Creek was a location that seemed ideal for a permanent home. It was located on the main thoroughfare through the Utah Territory about 15 miles southwest of Nephi, and no doubt many weary travelers to parts south, such as Cedar City, stopped there to rest from their journey. They must have found the shade of the cottonwood trees and thick willows, and the abundant flow of the creeks merging there very appealing. After leaving Beaver, the Morgans were among a small group who attempted a settlement in the location of Chicken Creek. Once again they started from scratch. They were living there in 1862 when Martha gave birth to a daughter, Martha Ettie on 24 August, and were there yet when another son James Nathaniel was born on 2 October 1864.33 The Morgans helped to build a community in Chicken Creek. They had erected a meeting house which doubled as a school and social hall. They had put in gardens and wheat fields. But Chicken Creek was still not to be their permanent home. It must have been with some disappointment that they concluded that the location that looked so ideal was unsustainable to their needs. The soil was actually quite poor, and the growing season too short to allow the cultivation of fruit trees. The water dwindled in -9- the fall, and locusts often devoured what crops could be raised.34 There were still Indian conflicts. In May of 1866, most of the residents moved temporarily to the fort in Nephi as a defense against attacks, but returned for the harvest in the fall.35 By 1867 the residents of Chicken Creek were exploring the area for a more sustainable location. They found it by following the creeks to their source. About a mile west of the canyons from which the water flowed they found a grassy, level tract which was to become their new, and for the Morgans, their permanent home. William, Martha, and their five remaining children were among the first to make the move to the new town site in 1868. Martha gave birth to another son, Ira Robert Morgan in February of that year, probably just prior to their move.36 President Brigham Young made the town official when he passed through, meeting with the Saints on 25 September 1868. He and a company of church officials stopped there that day, speaking to a congregation under the bowery in the town square. Brother Brigham personally gave the town a name: Levan.37 Even at the new location the first year was difficult. Locust still destroyed their crops, except for potatoes.38 But, characteristically, they endured. William Morgan was one of the two men given responsibility for temporal affairs in Levan by Elder Erastus Snow. Each family was allotted half a block, or 2.5 acres of land within the town boundaries, as well as twenty acres farm and pasture land outside. William and Martha selected a lot at what was then the center of town at the southwest of the junction of Main Street (now 1st West) and Canyon Lane. Here William built a log house, consisting of three rooms, all in a row. The roof was constructed of cottonwood sticks supporting a layer of clay and straw, covered with a layer of soil.39 The Morgans shared their block with Jacob Hofheins, Mormon Battalion veteran, his two wives and large family. The Hofheins family had lived in Parowan and had been part of the first group sent to support the Iron Mission. They had also moved from Chicken Creek and so the two families were undoubtedly well acquainted. In the years to come intermarriage would make them closer yet.40 The United Order From the Encyclopedia of Mormonism: "United orders" refers to the cooperative enterprises established in LDS communities of the Great Basin, Mexico, and Canada during the last quarter of the nineteenth century in an effort to better establish ideal Christian community and group economic self-sufficiency... Economic goals of consecration included relative income equality, group self-sufficiency, and the elimination of poverty. Under this plan, the head of each family would consecrate or deed all real and personal property to the Presiding Bishop of the Church and would receive, in turn, a stewardship, or "inheritance," from consecrated property. Thereafter, Church members would consecrate annually all surplus production from their stewardships to the bishop's storehouse. -10- The United Order was introduced into the Levan Branch in 1875. In late October and early November, William and Martha entered into the Order by covenant through the token of baptism. Children Martha Ettie, James Nathaniel also joined, as well as married son Daniel with his wife. A total of 113 persons joined the United Order at that time, with the number increasing to 273 by 1878. In spite of growing numbers, the Order eventually ceased to function in Levan, as it did in most Utah communities where it was attempted.41 Life in Levan William Morgan appeared before the First Judicial Court in Provo in October 1871 and became an American citizen.42 By virtue of her marriage to William, Martha now became an official citizen herself, renouncing legally her allegiance to Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. After years of sacrifice and travel, the Morgans were settled into a pastoral lifestyle on land of their own, surrounded by family. It was to be altogether too brief. If family tradition is correct, William suffered from the symptoms of asthma.43 There can be no doubt as to the source of his affliction. A glance at the history of his fathers, and his own occupational experience in the mines tells the story. His decline would have been gradual, the great strength from years of hard labor being sapped by his respiratory weakness. William Morgan died on 24 November 1876 in Levan.44 He was 59 years old when the cold specter of the coal mine which had haunted generations before him finally claimed his life also. He was buried in the cemetery southeast of the town. It was the location he himself, as one of the city fathers. had helped to select just a few years earlier.45 Martha was 52 years old and a widow. Within two years she suffered further sorrow when she lost her dear sister Jane, still living in Beaver and a highly respected midwife, to a relatively early death.46 She remained in Levan for the rest of her life. She watched from under the shade of the fruit trees planted by the hand of her husband47 as the plot of tall blue grass grew into an industrious little town. Many businesses sprung up, including a broom factory operated by son Daniel.48 She witnessed the raising of three church meeting houses, from the simple log structure a few blocks north of her home, to the present stately brick church with gothic windows, under construction when she died. And before the end of her life, even the miracle of telephone had reached this former frontier settlement.49 Martha's life was certainly one of industry. While her sons toiled in the fields, she would have supported them planting and harvesting gardens, preserving fruit from the orchard, cooking and mending. Wrestling with the notoriously hard water coming from the canyon springs must have been a massive chore on wash day in and of itself. It was a life of labor, but that had become the only life Martha knew. -11- Her Children On Thursday 1 March 1900 at a routine “Old Folk's Festival” held at the Levan Opera House (yes, there really was an opera house in Levan), a fine evening of banquet and entertainment was had. After the dinner, prizes were awarded to various persons present recognizing life accomplishments. First prize was awarded to Martha Morgan for a supreme achievement: 11 children, 55 grandchildren, and 45 great-grandchildren.50 It represented an ideal which must have been admired by others, but was certainly at the very core of her own life. No description of Martha's life would be complete without a snapshot of the children that surrounded her, both near and far, as the new century began. Catherine Banks Morgan, age 58, now known as Katie Ellison was running a boarding house in a mining town west of the Beaver-Milford area with two children. She and husband George and 4 children lived next door to her parents in Levan in 1870. George obtained employ in the gold mines near Minersville and they lived there with 9 children in 1880. She eventually moved to Salt Lake City with a daughter and family, where she died in 1923. Daniel Morgan, age 55, was farming in Wellington, Utah. He was widowed, living with 6 sons, a widowed daughter, and 4 grandchildren. He had married Clarissa Baxter in the Endowment House in 1867. Initially living in Nephi, they moved to Levan by 1870 where they remained until about 1876, then moving to Aurora, in Sevier County, and on to Carbon County in about 1889, where he operated a cattle ranch.51 They had 11 children. Daniel preceded his mother in death in 1902. Agnes Morgan Cook, age 53, was living in Uintah County with her day laborer husband James, 3 children and a boarder. She had given birth to 9 children, with 6 surviving. She and James were married in the Endowment House in 1869. They lived in Nephi and Levan (where her husband owned a store), in addition to Wayne and Uintah counties. After 1900 they moved to Idaho living in several locations. After the death of her husband, Agnes lived with a daughter in Ririe, Idaho. Both she and her husband were remembered as true and faithful, having lived full lives of service.52 Jane Nelson Morgan Sly died in Aurora, Utah in 1889 at the age of 40, and was buried in Levan. She had married Amos Gustin Sly in 1873 in Levan and they had lived there until moving to Aurora with brother Daniel. They were the parents of seven children. Their marriage was sealed in the new Manti Temple in 1888. Edward Nelson Morgan, age 43, was living in Beaver, working as a farmer. He had married a first cousin Martha Jane Patterson in 1881. Three sons and a daughter died as children, two daughters survived to adulthood. Their marriage was sealed in the Logan Temple in 1886. Edward died in Beaver in 1923, remembered as a kind husband, loving father and devoted to his religion.53 -12- John Athos Morgan, age 40, had married in 1890 and was the father of two sons. He farmed in Levan for his entire life. He was serving as the first president of the town board of newly incorporated Levan at the time.54 His current marriage was sealed in the Manti temple in 1894. His first wife died in 1902, and he married Elsie Paystrup the next year in the Manti temple. Three sons were born to this marriage. John died in 1919. Martha Ettie Morgan May, age 38, was living in Sandy, Utah with husband William, a smelter worker, and 8 children. They had married in 1881 in Levan and had lived in Juab before moving to the Salt Lake City area about 1890. She died in Salt Lake County in 1945 at the age of 82. James Nathaniel Morgan, age 36, was still unmarried and living at home with Martha at this time, and farming. In 1909 James, 45, married Eliza Hofheins, 39. Eliza had lived on the same block as the Morgan family in Levan for her entire life. They had two children before James died of tuberculosis in 1917. Ira Robert Morgan, age 32, was also a lifelong resident of Levan, and a farmer. He had married neighbor Mattie Hofheins (sister to Eliza) in the Manti temple in November 1894, on the same day brother John A. and first wife were sealed. In time they were the parents of eight children. Ira died of heatstroke in 1931 at the age of 63 while working in the fields with his sons.55, 56 Joys and Sorrows Martha Morgan was true to the faith she had embraced in Scotland, and for which she had sacrificed so much, to the end of her life. As with all who seek for a Zion, her faith was surely tried: tried by noble plans that somehow failed to be realized in spite of every possible effort; tried by the nature of dear ones who probably failed to rise to their divine potential in this life. She must have been disappointment to learn of the excommunication from the Church of her brother John Nelson in 1874. John had served well in the church in Scotland, emigrated to Utah and settled in Cache Valley becoming very wealthy through his abilities. However, he had failed to give heed to a statement of President Brigham Young. Brother Brigham said, “The worst fear that I have about this people is that they will get rich in this country, forget God and His people, wax fat, and kick themselves out of the Church...” John pretty much fulfilled the prophetic statement to the letter. Martha's sorrow would have been multiplied had she heard of the escapades of John's son, who became the infamous “Black Jack” Nelson, a notorious cattle rustler and stagecoach robber in 1880's southern Idaho.57 -13- But disappointment must have come closer to home when her son James was excommunicated on 10 Aug 1901. Levan Ward records show the charge of “neglect of duty, unbelief, and contempt” being leveled against him and 10 other Levan men, for which they were cut off from church fellowship.58 Martha and James lived under the same roof for 5 years with this little rain cloud probably never very far away. Happily, James was reinstated before the end of his life (but not Martha's). He was again ordained to the office of Elder by his brother John on 28 January 1917, about a year before his death.59 A Life in Review All things considered, Martha had much for which to rejoice as her mortality came to a close. She still possessed in her heart the conviction of an ideal which had sustained her through persecution, the crossing of an ocean, and the walking of a continent. She had escaped a social system which had held her forefathers captive for centuries, and was now enjoying the benefits of the rich heritage her late husband had bequeathed her: land of her own, and strong sons to work it. And she must have smiled kindly as she observed the majority of her children following the trail she and William had blazed, notwithstanding their shortcomings. Martha Matilda Nelson Morgan Martha Morgan had found her Zion. Martha Matilda Nelson Morgan died the day after Christmas at 6 pm in the year 1906 . Her oldest living son Edward was present from Beaver and acted as the informant as the death certificate was duly filled out. The cause of death: old age. She had lived for 82 years, 1 month and 7 days.60 She was laid to rest in the Levan cemetery, next to her husband, whose absence she had quietly endured for 30 years. The grave of her daughter Jane was very near. Today, the grave site is distinguished by a marker, stately and slate gray. It reminds us of the names of those whose remains wait there, and the duration of their lives. And it offers us this warm reassurance, engraved permanently in the stone and framed neatly in palm leaves, the symbol of eternal life: “The faithful are certain of their reward.” -14- Notes 1. Parish Records. Inveresk, Scotland. Family History Library [FHL] Microfilm 1067757, Family History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. 2. Carson, Robert. The Story of the Neilsons of Midlothian. www.carsontree.talktalk.net : 2011. 3. ibid. 4. Freese, Barbara. Coal: A Human History. Perseus Publishing, 2003. 5. Carson, The Story of the Neilsons of Midlothian. 6. Ancestry.com. 1841 Scotland Census [Database on-line]. Provo, Utah, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc. 2006 7. Scotland, Lanark, Old Monkland—Church Records, Marriage Proclamations, 1819-1850. Family History Library [FHL] Microfilm 1066602, Family History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. 8. 1841 Scotland Census [Databaase on-line] 9. Old Monkland Strikes, Court Cases & Misc. www.scottishmining.co.uk, 2011. 10. FamilySearch. LDS Church Membership Records. www.new.familysearch.org, 2011. 11. Record of Members in Dunfermline Branch. Family History Library [FHL] Microfilm 104150, Family History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. 12. Record of Members in Oakley Branch. Family History Library [FHL] Microfilm 104154, Family History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. 13. Kendall, Alan M. The History of the Morgan Family (Unpublished), and www.new.familysearch.org, 2011. 14. The History of the Morgan Family. 15. Ancestry.com. New Orleans Passenger Lists, 1820-1945 [Database on-line]. Provo, Utah, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc. 2006. Jane Morgan traveled with Martha and family. 16. The History of the Morgan Family. 17. Mormon Migration, Liverpool to New Orleans, Ship: James Pennell. http://lib.byu.edu/ mormonmigration, 2011. 18. Ancestry.com. 1850 U. S. Federal Census [Database on-line]. Provo, Utah, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc. 2009 19. Sly, Jeffery. Notes on Andrew Patterson, new.familysearch.org. 20. Jane and Andrew Patterson are thought to have crossed in the 1852 Higbee/Bay company ( Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel, 1847–1868 at www.lds.org) with her brother John Nelson and his family. Her 18 Sept 1878 obituary in the Deseret News incorrectly states that she arrived in Salt Lake valley 13 May 1852, but probably intended to say that their company left Council Bluffs at that time. 21. Utah Bishops’ Report 1852. Family History Library [FHL] Microfiche 6051208, Family History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. 22. Marlin, Don. Early Settlers of Levan, p. 252. 23. LDS Church Membership Records. 24. Index to Patriarchal Blessings: 1833-1963. Family History Library [FHL] Microfilm 392673, Family History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. 25. Endowment House Records. Family History Library Special Collections [FHL] Microfilm 1149524, Family History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. 26. Shirts, Morris A. A Trial Furnace. Brigham Young University, University Publications. 2001. 27. LDS Church Membership Records. 28. A Trial Furnace. 29. LDS Church Membership Records. 30. Dalton, Luella. History of Iron County, p. 200. Family History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. 31. Ancestry.com. 1860 U. S. Federal Census [Database on-line]. Provo, Utah, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc. 2009 32. LDS Church Membership Records. 33. ibid 34. Stephensen, Maurine. A History of Levan, p. 5. Chicken Creek Camp, Daughters of Utah Pioneers. 35. McCune, Alice P. History of Juab County, p. 152. Juab County Company, Daughters of Utah Pioneers. 1947. 36. LDS Church Membership Records. 37. A History of Levan, P. 13. 38. ibid. 39. ibid. 40. ibid. 41. Records of Levan Ward. Family History Library [FHL] Microfilm 26125, Family History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. 42. District Court Minute Book, p. 562, Provo, Utah. Family History Library [FHL] Microfilms 482920-482921, Family History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. 43. Interview with Lorene Morgan and Nina Morgan. Audio tape in possession of author. 44. LDS Church Membership Records. 45. A History of Levan, P. 12. 46. Salt Lake City. Deseret News, 18 September 1878, p. 528. 47. History of Juab County, p. 154. 48. ibid, p. 156. 49. ibid, p. 166. 50. Salt Lake City. Deseret Evening News, 7 March 1900. 51. Lennstrom, Elva Curtis. History of Daniel A. Morgan. Daughters of Utah Pioneers. 1968. 52. Moss, Nora E. Agnes Beverage Morgan Cook 1846-1934. Lovell Family History Website, http://lovellfamilyhistory.blogspot.com/search/label/Morgan. 53. Obituary of Edward Nelson Morgan. Southern Utonian, 15 June 1923. 54. A History of Levan, pp. 68-70. 55. Copy of Obituary of Ira Robert Morgan, in possession of author. 56. Historical sketches of children taken from information in www.new.familysearch.org and various census records. 57. A. J. Simmonds. The Gentile Comes to Cache Valley: A Study of the Logan Apostasies of 1874 and the Establishment of Non-Mormon Churches in Cache Valley, 1873-1913. Logan: Utah State University Press, 1976. p. 79-82. 58. Records of Levan Ward. 59. ibid. 60. Utah Death Certificates, 1904-1956. FamilySearch. Www.familysearch.org. Martha M. Morgan.