VET System Reform - Consultant Report

advertisement

THE REVIEW OF THE ROLE AND FUNCTION OF

TASMANIA’S PUBLIC SECTOR VOCATIONAL

EDUCATION AND TRAINING (VET) PROVIDERS

CONSULTANT’S REPORT

Virginia Simmons A.O.

30 April 2012

Final Version

Doc ID: TASED-4-1410

1

2

REPORT OF THE REVIEW OF THE ROLE AND FUNCTION OF

TASMANIA’S PUBLIC SECTOR VOCATIONAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING (VET) PROVIDERS

Table of Contents

SECTION

Page No

1.

INTRODUCTION

6

2.

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

8

3.

3.1

3.2

3.3

3.4

CONTEXT

The Impetus for the Review

Issues Arising out of the Current Model

Some Key External Trends and Developments Since 2008

The Wider VET Market

14

4.

4.1

4.2

4.3

4.4

4.5

METHODOLOGY

Terms of Reference

Reference Group

Approach Adopted

The Public Consultation Process

Written Submissions

23

5.

5.1

5.2

5.3

5.4

CONSENSUS ACHIEVED

Common Themes

Principles for Change

Specific Proposals for Change

Commentary

26

6.

6.1

6.2

6.3

VET IN TASMANIA – ITS IMAGE AND IDENTITY

Image and Identity

The Definition of VET

Recommendations 1-2

31

7.

7.1

7.2

7.3

A VISION FOR PUBLIC SECTOR VET IN TASMANIA

Positioning for the Future

Other Considerations that Inform the Vision

Recommendation 3

34

8.

8.1

8.2

8.3

THE LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK

The Current Legislative Framework

The Need for a New Legislative Framework

Recommendations 4-6

37

Doc ID: TASED-4-1410

3

9.

9.1

9.2

9.3

9.4

9.5

9.6

9.7

9.8

9.9

9.10

9.11

THE FUTURE STRUCTURE FOR POST-COMPULSORY PUBLIC SECTOR VET

One Entity

Building on the Gains, Not Returning to the Past

Organisational Governance Arrangements

Organisational Structure

Guidelines for Positions

Appointment Processes

Centres of Excellence

Corporate Services

Assets and Infrastructure

The Future of Teacher Registration in the New Entity

Recommendations 7-24

39

10.

10.1

10.2

10.3

GOVERNANCE OF THE SYSTEM

Overview

Potential Future Arrangements

Recommendations 25-30

52

11.

11.1

11.2

11.3

11.4

11.5

11.6

VET PROVISION IN SCHOOLS/COLLEGES

The National Scene

The Tasmanian Scene

Cultural Differences

Funding

Future Trade Training Centres

Recommendations 31-38

55

12.

12.1

12.2

12.3

12.4

VET AND HIGHER EDUCATION

The National Tertiary Landscape

VET/Higher Education Collaboration in Tasmania

Building a Strategic Partnership

Recommendations 39-42

61

13.

13.1

13.2

13.3

13.4

ADULT LEARNERS

Clarifying Policy

The Role of LINC Tasmania

Adults in VET

Recommendations 43-48

67

14.

14.1

14.2

14.3

14.4

14.5

14.6

VET IN RURAL AND REMOTE AREAS

The Challenges

Thin Markets

Maintaining Sustainable Levels of Delivery

Facilities

Alternative Learning Methodologies

Recommendations 49-51

70

Doc ID: TASED-4-1410

4

15.

15.1

15.2

15.3

MARKETING, BRANDING AND NOMENCLATURE

The Main Brand

Sub-branding

Recommendations 52-53

74

16.

16.1

16.2

16.3

IMPLEMENTATION

Effective Implementation

Supporting Staff and Students in the Change

Recommendations 54-60

77

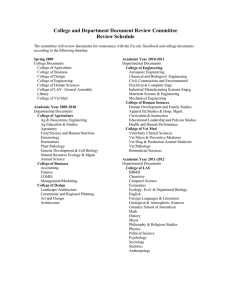

BOXES

Box 1

Box 2

Box 3

Box 4

Box 5

Box 6

Box 7

Box 8

Box 9

Box 10

Box 11

Box 12

Box 13

Box 14

7

14

15

16

22

23

24

28

35

36

52

52

61

65

Box 15

Box 16

Tasmania’s New Public Sector VET Entity – Integrated and Interconnected

Extract from the Review Consultation Paper

Targeting Different Learner Cohorts – Example 1

Targeting Different Learner Cohorts – Example 2

Private RTOs in Niche Markets – Case Study

Terms of Reference of the Review

Approach Adopted for the Review

Summary of the Common Themes

Skills Tasmania’s Vision for VET

Two Public Sector Visions

Governance of Public Sector VET in Tasmania – ‘Tasmania Tomorrow’

Governance of Public Sector VET in Tasmania – 2010 to Present

Public Sector VET Entities Registered as Higher Education Providers

Graduating Students at Qualifications Levels AQF 1-6, Tasmanian

Polytechnic, 2009-11

VET Effort by Age Group – Tasmania and Australia 2010

Use of ‘TAFE’ By Public Sector VET Providers

APPENDICES

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Appendix 5

Appendix 6

Appendix 7

Appendix 8

Appendix 9

Appendix 10

Key Data for Tasmania

Consultation Paper for the Review

Case Studies of Mainland RTOs Operating in Tasmania

Public Consultations

Written Submissions

A New Single Entity for VET in Tasmania – Indicative Structure

The Future of Teacher Registration in the New Entity

Governance of Public Sector VET in Tasmania – Possible Future Model

Acronyms and Abbreviations

References

79

85

86

88

89

91

92

97

98

99

Doc ID: TASED-4-1410

69

74

5

1.

INTRODUCTION

This Report was commissioned by the Hon Nick McKim MP, Minister for Education and Skills, as the

outcome of the Review of the Role and Function of Tasmania’s Public Sector VET Providers. It has

been the consultant’s privilege to undertake the Review and to receive a high level of constructive

input from well over 300 stakeholders in the VET system from across Tasmania: students, teachers,

administrators, industry and community leaders, employers, parents and government

representatives. A debt of gratitude is owed to all those individuals and the organisations they

represent.

As encapsulated in the State’s Economic Development Plan:

Tasmania is a small, beautiful and remote part of the world with unique features and rich

natural resources that the world increasingly values. 1

With a small and dispersed population and an increasingly competitive global environment, it faces a

number of challenges in achieving a robust economy with sufficient industry to sustain full

employment, productivity and growth. Appendix 1 provides key supporting data which is evidence

of these challenges.

As the Economic Development Plan makes clear, the VET system plays an important role in:

•

•

•

•

supporting the economy by meeting the training needs of traditional and emerging industries so

that they can take advantage of market opportunities (Goal One – to support and grow

businesses in Tasmania)

assisting individual industries by addressing skills gaps and skills shortages (Goal Two – to

maximise Tasmania’s economic potential in key sectors)

contributing to social sustainability and inclusion by improving skill levels that increase

workforce participation to reduce inequality and poverty (Goal Three – to improve the social and

environmental sustainability of the economy)

developing skills that achieve a more resilient and diverse economic base in Tasmanian

communities (Goal Four – to support and grow communities in regions). 2

More generally, VET also enables individuals to access accredited programs that support their career

goals. It is therefore critical that it facilitates seamless pathways at the interface with other sectors

of education that promote skill deepening and further study.

Commencing in 2009, the former TAFE Tasmania was separated into two entities – the Tasmanian

Polytechnic and the Tasmanian Skills Institute (TSI) – each charged with a different mission and

function. The Tasmanian Polytechnic’s role is to lift the participation and attainment of individuals.

The TSI has a productivity focus, namely meeting the skill needs of enterprises and employed

workers.

Following this and other structural changes, the public VET system has experienced a decline in

efficiency and effectiveness in recent years and has lost the confidence of some parts of the industry

and community it serves. It has become clear that such a split is not straightforward or ‘clean’ and

that VET students/learners and operations do not lend themselves to such neat

1

Department of Economic Development, Tourism and the Arts, 2011, Economic Development Plan Overview, Tasmania,

p.4

2

Ibid, p.10-17

6

compartmentalisation. The system is now variously seen to be characterised by fragmentation,

confusion, inconsistency, internal competition, wastage, patchy quality and an internal focus.

Despite these problems, the structural changes brought forth some important innovation and

genuine successes. The two different emphases meant that new partnerships, new learning models

and new approaches have evolved, which otherwise might not have. These are widely considered to

be well worth maintaining.

This Report does not set out to diagnose in any detail the problems that have occurred in the past.

The intention is to look to the future and to identify strategies to place the public VET system on an

entirely new footing: one that addresses the problems but also retains and builds on the gains made.

A new single entity is proposed that is internally integrated and externally interconnected. The

recommendations provide details of how this is to be achieved. The emphasis is on tailoring a set of

arrangements that will work for the particular circumstances in Tasmania, not to overlay a model

from another context.

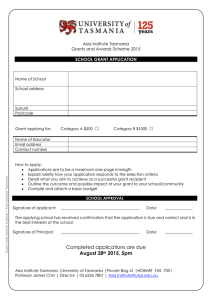

Box 1 is a visual representation of how this will operate in practice.

Box 1: Tasmania’s New Public Sector VET Entity – Integrated and Interconnected

ADULT &

COMMUNITY

EDUCATION

COLLEGES/

SCHOOLS

INDUSTRY

BODIES

THE NEW

PUBLIC SECTOR

VET ENTITY

Participation/

Attainment

Productivity/

Work Readiness

HIGHER

EDUCATION

(UTas)

INDIVIDUAL

ENTERPRISES &

WORKPLACES

PRIVATE

RTOs

7

2.

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

Below is a summary of the recommendations of this Report, ordered by section heading.

It is recommended that:

VET in Tasmania – Its Image and Identity

R1

To re-affirm Tasmania’s important role in the national VET system, a standard description

be adopted for VET in Tasmania that is brief, accessible and accurate, and that it be used

consistently in documentation about the sector until such time as the meaning of VET is

better understood.

R2

Related terminology such as Vocational Education and Learning (VEL) and leisure and

lifestyle programs be clarified and actively promoted in a way that assists this distinction.

A Vision for Public Sector VET in Tasmania

R3

The Tasmanian Government, as the owner of the public VET system, consider articulating a

vision for its future that is communicated to the Tasmanian community.

The Legislative Framework

R4

All aspects of VET governance, delivery, administration and co-ordination be covered by a

single, contemporary and aspirational piece of legislation and the objects and provisions of

the legislation be written so as to ensure all components of public sector VET are working

towards a common goal.

R5

The new entity be designated as a statutory authority with the capacity to employ its own

staff.

R6

The Objects of the Act contain reference to:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

ensuring Tasmania’s VET system supports the needs of Tasmania’s economy and the

aspirations of Tasmania’s citizens

providing for the effective delivery of VET to individuals and industry in Tasmania

ensuring mechanisms exist to enable industry’s training and workforce development

needs to be understood and met

promoting alignment between VET offerings and the needs of the Tasmanian labour

market

promoting pathways between VET and the other educational sectors

providing for public sector VET to have the independence and flexibility it needs to

respond to the needs of industry and the community

fostering quality and innovation in VET.

The Future Structure for Post-Compulsory Public Sector VET

R7

A new single entity be created for public sector post-compulsory VET in Tasmania using the

combined resources of the Tasmanian Polytechnic and TSI.

8

R8

Steps be taken to ensure that the new entity retains the capacity to focus specifically on

each of the productivity/work readiness agenda and the participation/attainment agenda.

R9

The scope of registration of the existing Tasmanian Polytechnic and TSI be unified as part

of the creation of the new entity.

R10

The new entity be a statutory authority within the proposed new VET Act and have the

capacity to appoint its own staff.

R11

The membership of the Board reflect the characteristics of the community and industry the

new entity serves and include experts from areas such as other educational sectors,

finance, human resources, risk management, property and the law.

R12

The initial organisational structure have the following characteristics:

•

•

•

•

•

•

flat and lean, with minimum layers of responsibility and empowered managers

managers expert in their disciplines/industries of responsibilities

a clear and single line of responsibility for teaching areas

capacity to maintain a separate focus on the two strands of productivity/work

readiness and participation/attainment

a distributed rather than centralised approach to location of senior staff

identification of existing or potential Centres of Excellence across the delivery

areas as a focus for capability and future development.

R13

A nation-wide search be conducted for the recruitment and appointment of the CEO as

soon as practicable, to lead the development and vision for the new entity.

R14

Other senior positions in the new structure be appointed in accordance with State Service

processes.

R15

The accountabilities and selection criteria for senior positions be crafted so as to ensure

the organisation works effectively in accordance with the characteristics outlined in

recommendation 12.

R16

Staff in charge of teaching areas be required to work to industry advisory bodies or

alternatively authoritative industry mentors in the areas for which they are responsible.

R17

Management of the operations of teaching sites be separate from the management of

teaching programs and include responsibility for ensuring the delivery arrangements for

remote and rural areas are maximised, including through coordination with

schools/colleges.

R18

All teaching sites operated by the new entity have a designated point of contact.

R19

Communication strategies about the new structure include all staff regardless of the level

or category of appointment.

9

R20

The importance of an effective VET/tertiary specific student administration/management

system for conducting the core business of the new entity be recognised, and that it

accordingly be managed by the new entity with all information accessible by the relevant

government authorities.

R21

In principle, the current provision of corporate services by the Department of Education

(DoE) continue for all other systems at least until the new entity is established and is in a

sound financial position.

R22

For the foreseeable future, ownership of the assets and infrastructure be vested in the

Crown.

R23

Subject to some minor amendments to the Teachers Registration Act 3 to ensure VET

coverage, teacher registration be extended across the whole of the new entity.

R24

The initial emphasis of the new entity be on consolidating the fundamentals of teaching,

learning and assessment; ensuring access for students; and building industry relevance to

create a dynamic and innovative teaching and learning environment.

Governance of the System

R25

Statutory authorities in the future public VET sector be established under the proposed

new VET Act.

R26

The Minister’s ultimate responsibility for all aspects of VET policy be clearly articulated in

the new VET Act.

R27

The Minister designate responsibilities for the productivity/work-readiness agenda and the

participation/attainment agenda at state level, mirroring and consolidating the

arrangements proposed at provider level for the new entity along the lines outlined in

Appendix 8.

R28

Skills Tasmania be re-named the ‘Tasmanian VET Commission’ (or similar) to better reflect

its function and avoid confusion about its role.

R29

The Tasmanian VET Commission (or similar) retain statutory authority status under the

proposed new VET Act.

R30

The Department of Education be renamed ‘Department of Education and Training’.

VET Provision in Schools/Colleges

R31

A network of providers of VET in schools/colleges be formalised, consisting in the first

instance of:

•

•

•

3

the eight existing colleges

the existing Trade Training Centres and their partner schools

any high schools that currently have Registered Training Organisation (RTO) status.

Refer Appendix 7

10

R32

The existing RTO arrangements be fixed for the time being and reviewed in 2015, unless

voluntary relinquishment of such status is initiated in the meantime.

R33

Existing auspicing arrangements between the colleges, Trade Training Centres and the

Tasmanian Polytechnic be transferred to the new entity and expanded over time.

R34

DoE host a formal structure to enable ongoing liaison between the network and the new

entity to ensure:

•

•

•

•

the necessary programs are on scope

auspicing arrangements are appropriately monitored

the delivery requirements of the network are met as far as practicable

arrangements for duty of care and pastoral support are agreed.

R35

As the opportunity arises, steps be taken to ensure that there is a mix of staff from college

and VET backgrounds involved in pathway planning.

R36

The funding arrangements for provision of VET in the network be reviewed to move

towards closer alignment with the true cost of VET delivery.

R37

The decisions on the location of any new Trade Training Centres take into account an

optimal geographic coverage across the state, including rural and remote areas.

R38

A business plan be developed for each Trade Training Centre to maximise its usage beyond

the requirements of the school sector, with priority for those seeking access to accredited

outcomes.

VET and Higher Education

R39

A forum be created to enable the new entity and the University of Tasmania to develop a

formal, multi-dimensional and strategic partnership with the aim of becoming a model for

Australia.

R40

A joint investigation be conducted into possible funding sources that might support the

work involved in developing the partnership.

R41

Consideration be given to placing priority on joint arrangements to support growth in the

international market.

R42

Strategies be developed to restore the percentage of graduates qualifying at

Diploma/Advanced Diploma level to at least 2009 levels.

Adult Learners

R43

Work be undertaken to clarify the policy framework for adult and community education

clearly differentiating between that activity which is part of VET (i.e. leading to accredited

outcomes) and that which is leisure and lifestyle related or pre VET.

R44

VET government funding directed to adult and community education place priority on

adults pursuing qualifications for work related purposes.

11

12

R45

The LINC Tasmania network be re-affirmed as an important and useful gateway for adults

into VET, but not part of the formal VET sector.

R46

LINCs be excluded from obtaining RTO status.

R47

The training needs of volunteer tutors continue to be monitored so as to stage the

allocation of funding to progressively meet this need.

R48

Provision of VET across the age cohorts in Tasmania continue to be monitored for

alignment with national trends.

VET in Rural and Remote Areas

R49

Measures be developed to ensure a sustainable level of provision in rural and remote areas

consistent with demand and communicated to the communities concerned.

R50

Ongoing responsibility for ensuring adequate provision in rural and remote areas be

assigned in the final structure for the new entity.

R51

A compliance and viability audit of each existing campus/facility now operated by the

Tasmanian Polytechnic and TSI outside of Hobart, Launceston, Burnie and Devonport be

conducted to:

•

•

•

•

identify its current and past usage patterns, the likely future demand, and issues arising

from this

determine its capacity to effectively cater for future needs of the local industry and

community, especially as envisaged in the state’s Economic Development Plan

clarify the way forward for each associated community in terms of short, medium and

longer term investment

develop a strategic business plan for each campus/facility.

Marketing, Branding and Nomenclature

R52

The new entity adopt the name ‘TasTAFE’ as the main brand.

R53

A sub-branding strategy be developed to further differentiate component parts of the

operations, particularly Centres of Excellence and programs co-located with other

sectors/providers.

Implementation

R54

An implementation group be established to undertake the necessary work on

implementation within agreed time-lines.

R55

The CEO be appointed in time to be able to lead and manage the transition process and

participate in the filling of senior vacancies.

13

R56

Working groups progressively commence work in the following areas that are critical to

implementation:

•

•

•

•

•

•

Legislation and Governance

Human Resources

Programs, Enrolments and Services

Finance

Technology and Systems

Marketing, Branding and Communication.

R57

Working group membership be based on expertise rather than representation and include

nominees from DoE, Skills Tasmania, the Tasmanian Polytechnic and TSI as appropriate.

R58

Working groups have clear terms of reference and time-lines for achievement of

milestones.

R59

A minimum lead-time of six months be allowed for the working groups to undertake their

roles.

R60

A formal and regular communication process with stakeholders be part of the

implementation process.

14

3.

3.1

CONTEXT

The Impetus for the Review

The following extract from the Consultation Paper for the Review, issued by the

Hon Nick McKim MP, Minister for Education and Skills in December 2011, succinctly outlines some of

the major issues and reasons why the Review was needed:

Box 2: Extract from the Review Consultation Paper

Reform of the post-compulsory education and training sector in Tasmania over the last four years, including the ‘Tasmania

Tomorrow’ initiative, has resulted in two major public providers of VET; the Tasmanian Polytechnic and the Skills Institute.

There is also some provision to young students by colleges of the Tasmanian Academy and some district and regional high

schools.

The public providers have different structural and governance arrangements:

• The Tasmanian Polytechnic is situated within the Department of Education. Its role is to provide qualifications for

individuals to enable them to enter the workforce, further their skills and qualifications or enable a career change, as

well as provide pathways into higher education.

• The Skills Institute is a statutory authority accountable to the Minister for Education and Skills through a board. It is

focussed on skills development for employees in enterprises in line with the enterprises’ skill needs.

• Colleges of the Tasmanian Academy and a number of district and regional schools, also within the department, are

focussed on young Tasmanians in the 15-19 year old age group. VET is provided in conjunction with Tasmanian

Qualifications Authority accredited courses either directly by the colleges or in various partnering arrangements with the

Tasmanian Polytechnic and private registered training organisations (RTOs).

Skills Tasmania is a statutory authority that has a legislated function to purchase VET from public and private RTOs. It does

this in support of its sole statutory objective which is to ensure that Tasmania has a system that supports a productive

workforce and contributes to economic and social development in the state. It purchases VET from both of the major public

providers, some of which is undertaken contestably. Essentially all of the VET courses purchased from private RTOs is done

contestably.

The role of public VET providers is far greater than the delivery of qualifications. They have a role in implementing

government policy and in meeting identified skill needs. They provide economies of scale and effective infrastructure. They

enable provision in ‘thin markets’, increased access and the leverage of industry investment. A highly skilled and qualified

workforce supports increased productivity and growth. Tasmania has an aging population with a low level of post-school

qualifications.

Tasmania aspires to both state and national targets for participation in VET and the attainment of qualifications, and public

providers have a significant role to play in achieving these targets. Tasmania has agreed to a national target for Year 12 or

equivalent attainment of 90 per cent by 2015 through the National Partnership Agreement on Youth Attainment and

Transitions. As a state, Tasmania also has a number of other targets including:

Measure

Proportion of 15-64 year olds enrolled in

education or training

Target

20.6% (2015)

Source ABS 6227.0

Proportion of Tasmanians with high level

skills/qualifications (Certificate III +)

49% (2015)

Source ABS 6227.0

There is significant concern in the VET and broader community in Tasmania that the current model of VET provision by

Tasmania’s government providers is not optimal. A review of the current arrangements will determine if the structural

changes made in 2010 can deliver the outcomes required of the public VET system, and if not, recommend alternatives. 4

This final statement by the Minister was strongly confirmed during the conduct of the Review. A

complete copy of the Consultation Paper is included as Appendix 2.

4

McKim, Hon. N, 2011, Review of the Role and Function of Tasmania’s Public VET Providers (Consultation Paper),

Department of Education Tasmania, p.4

15

3.2

Issues Arising out of the Current Model

The splitting of the former TAFE Tasmania into two post-compulsory entities, namely the Tasmanian

Polytechnic and the TSI as part of ‘Tasmania Tomorrow’ was in part aimed at addressing a major

challenge facing many TAFE institutes across Australia. It is widely acknowledged that teachers

require different skills sets for different learner cohorts and different learning models apply. In

particular there are differences between those learners already in employment where the workplace

is integral to their training and those learners not in employment and potentially not yet even clear

about their career destinations. The latter group often consists of school leavers or those returning

to study, while the former group quite typically comprises apprentices and existing workers seeking

to upgrade their skills. In Tasmania, this distinction is referred to as participation and productivity,

where the focus for the first group is on retention and attainment, often in an institutional setting,

and the focus of the second group is on work readiness and skill relevance, often in a workplace

setting.

Public sector providers across Australia seek to cater for these groups in different ways and with

varying success, most often within the one organisation. They may, for example, set a percentage

target for delivery in the workplace, create specialist roles within the organisation structure or have

specialised professional development programs.

The creation of the Tasmanian Polytechnic and the TSI is just one example of how some states have

gone a step further in making significant structural or organisational change in an attempt to more

effectively meet the needs of these different learner cohorts. Box 3 provides one such example:

Box 3: Targeting Different Learner Cohorts – Example 1

Queensland – SkillsTech Australia

The Queensland Government decided to concentrate its apprenticeship training in one organisation under the

title of SkillsTech Australia. SkillsTech markets itself as ‘TAFE made for tradies’ and ‘Industry’s right hand’. The

following is an extract from its website:

SkillsTech Australia is Queensland's largest TAFE institute dedicated to trade and technician training in

automotive, building and construction, electrotechnology, manufacturing and engineering, sustainable

technologies and water.

We deliver pre-apprenticeship, apprenticeship/traineeship and post-trade training to more than 20,000 students

every year, at six Brisbane metropolitan training centres.

As part of the TAFE Queensland network, SkillsTech Australia works with industry to develop and deliver worldclass courses that provide relevant skills and best practice training.

We have a reputation for delivering the highest quality training with industry-standard equipment in safe, modern,

world-class facilities.

Our teachers are qualified tradespeople, who understand the need to train with the latest techniques and

technologies to meet industry standards. Students have access to hands-on training to ensure they are job-ready

for their employer. 5

With its focus on the trades, apprenticeship and pre and post-apprenticeship training, it can be seen

that SkillsTech has elements in common with the TSI in Tasmania. The specialisation is seen to be

advantageous for students and beneficial in attracting the most appropriate teachers.

5

http://www.skillstech.tafe.qld.gov.au/about_us/about.html

16

Box 4 provides a second potentially more far-reaching example in that it identifies four different

ways of working:

Box 4: Targeting Different Learner Cohorts – Example 2

Western Australia – Challenger Institute of TAFE

Challenger TAFE has developed a unique model of four paradigms, to inform and enrich its delivery of services,

briefly summarised as follows:

Paradigm 1: campus-based delivery

Training for industry and enterprises is delivered in high quality classroom, laboratory and workshop. Lecturers

and trainers are expert presenters, demonstrators and tutors.

Paradigm 2: college and workplace delivery

‘Your place or ours’. Training includes a blend of classroom and workplace delivery. The RTO hires both

campus-based lecturers and workplace trainers.

Paradigm 3: working within specific enterprises

Training embraces enterprise development, focusing on skill development for jobs. Trainers are work-based

learning facilitators and workforce developers.

Paradigm 4: industry and community workforce planning and development

The RTO embraces an industry and community skills ecosystem mindset. Trainers, designers, consultants and

teams operate inside the industry skills ecosystem. 6

In describing the four paradigms, the Institute uses the terms ‘productivity’, ‘participation’, ‘workforce

development’ and ‘skills development’.

This approach also has elements in common with both the Tasmanian Polytechnic and TSI.

These interstate examples illustrate that it would be a mistake to dismiss the creation of the

Tasmanian Polytechnic and TSI as an isolated instance of experimentation. As becomes clear in the

body of this Report, there is much to recommend the maintenance of the distinction that is inherent

in the two organisations, even though this might take on a new and different form.

3.3

Some Key External Trends and Developments Since 2008

The Minister acknowledged in the Consultation Paper that:

There are many factors currently confronting our public VET providers, including a significant national VET

reform agenda, the state’s challenging budget outlook and the reshaping of traditional provision by higher

education and private VET providers. We must determine whether our public providers are optimally

positioned to meet these challenges. 7

The many factors and external developments that have changed the wider education landscape

since the announcement of ‘Tasmania Tomorrow’ in 2008 merit further exploration if Tasmania is to

be well-positioned for the future. Among the more critical of these developments are:

6

7

Mitchell, J, 2007 Implementing the Four Paradigm Model of Service Delivery: Challenger TAFE Case Studies, TAFE WA p.3

McKim, Hon. N, op cit, p.3

17

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

the Global Financial Crisis (GFC)

the downturn in the inbound international student market, particularly in the VET sector

a new tertiary orientation

a demand-driven Higher Education sector

Council of Australian Governments (COAG) reforms

the establishment of the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA)

the Trade Training Centres program

the roll-out of the National Broadband Network (NBN).

Each of these is examined briefly below along with their potential implications for public sector VET

in Tasmania.

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC)

Early signs of an impending GFC occurred at about the same time as ‘Tasmania Tomorrow’ was being

announced. The first Australian Government responses were initiated in late 2008 after the collapse

of Lehmann Bros in the United States, but the impact of the GFC is still being felt today.8 Although

Australia is generally considered to have fared reasonably well in comparison to other countries, the

subsequent rise of the Australian dollar has affected education through, as just one example, its

impact on exports 9 . Many RTOs, public and private alike, have noted that in times of tight economic

constraints, such as are now being experienced, industry’s expenditure on training is likely to be

reduced with resulting effects on RTOs’ commercial income. In addition, since enterprises need to

be ‘lean’ and ‘smart’ in order to survive, training offered must be highly relevant and leading edge.

This is a key challenge that public sector VET has been facing and which is showing no signs of

diminishing.

For Tasmania’s public VET sector, provision needs to be highly competitive and relevant in the current

economic climate.

The Downturn in the Inbound International Student Market

In related vein, the international student market has fallen dramatically since 2009, particularly in

the VET sector. The Knight Review 10 identified the key reasons for this as:

•

•

•

•

•

•

the strength of the Australian dollar

the rapidity and magnitude of Australia’s migrant and student visa policy settings

damage to Australia’s reputation flowing from international students’ safety concerns

bad publicity from provider closures

the effects of the GFC

increased competition from international providers in other countries.

The Knight Review’s proposed streamlined visa processing for universities specifically excluded the

VET sector, although COAG agreed at the April 2012 meeting that this should now be extended to

high quality/low risk VET providers in the second half of 2012. However, it will take some time to

recapture the lost market share. The Knight Review recommended that the VET sector should focus

on developing its transnational education capability, that is, explore off-shore market

opportunities. 11 There is strong competition from mainland VET providers in this regard.

8

9

www.treasury.gov.au/documents/1576/HTML/docshell.asp?URL=Australia_Israel_Leadership_Forum_by_Steven_Kennedy.htm

Economic Development Plan, op cit, p.7

Knight, M, 2011, Strategic Review of the Student Visa Program, Australian Government, p.11-13

11

Ibid p.xiii -xviii

10

18

There is potential for the Tasmanian public sector VET system to partner with the University of

Tasmania (UTas) and jointly market programs and services.

For Tasmania’s public VET sector, strong Higher Education linkages, which provide a potential

mechanism to prosper in the inbound international student market, may need to be further

developed as well as transnational education opportunities.

A New Tertiary Orientation

The 2008 report of the review of Higher Education in Australia 12 led by Prof. Denise Bradley

(hereafter the Bradley Review) found that it was time to move away from the two distinct sectors of

VET and Higher Education to a continuum of tertiary education. The Report stated:

Various efforts to strengthen the connections between higher education and VET have been made in

Australia over the last twenty-five years with limited success, due to structural rigidities as well as to

differences in curriculum, pedagogy and assessment. The review has considered both why a better interface

between higher education and VET is now imperative as well as the broad range of ways in which it could be

pursued. While the issues to be dealt with are complex, reform is vital if a fully effective tertiary system … is

to be achieved. 13

The Report also outlined six key characteristics of an effective tertiary education and training system

as well as making several recommendations to support this change, structural elements of which

included:

•

•

•

•

•

a Review of the Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF) with a refined, single architecture –

now complete (Recommendation 24)

the move towards a single national tertiary regulatory body covering both Higher Education and

VET – now consisting of the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) and the

Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) with a goal that they ultimately merge

(Recommendation 43)

the establishment of a single Ministerial Council with responsibility for all tertiary education and

training – now the Standing Council on Tertiary Education Skills and Employment (SCOTESE)

which has also established a Tertiary Education Quality and Pathways as one of its Principal

Committees (Recommendation 46)

extension of the scope and coordination of labour market intelligence to cover the whole

tertiary sector and support a more responsive and dynamic role for both vocational education

and training and higher education – achieved through an expanded role for Skills Australia, renamed the Australian Workforce and Productivity Agency (Recommendation 46)

expansion of the purpose and role of the National Centre for Vocational Education Research

(NCVER) to cover the whole tertiary sector – achieved (Recommendation 46).

In response to the changes, many public sector VET providers set about positioning themselves for a

tertiary future, with initiatives such as:

•

•

•

•

investing increased effort in developing Higher Education partnerships and pathways

placing greater emphasis on developing and marketing higher level VET qualifications,

Diplomas, Advanced Diplomas and Vocational Graduate Certificates

becoming registered as Higher Education providers, offering Higher Education qualifications

such as Associate Degrees, Bachelor Degrees, and in a few instances, Masters Degrees

rebranding to reflect a broader offering than just VET/TAFE.

12

Bradley, D, Noonan, P, Nugent, & Scales, B, 2008 Review of Australia’s Higher Education System – Final Report,

Commonwealth of Australia

13

Ibid, p.179

19

For example, one Victorian TAFE institute enrolled its first Higher Education students in 2009 and

now offers 13 Associate Degrees and 13 Degrees. This has considerable implications for the

qualifications and capacity of staff and the capability of the institute as a whole.

TAFE now offers Higher Education in every Australian state except Tasmania and the Northern

Territory where it is part of a dual sector university.

Given that Tasmania is the only state in Australia with one university, it is debatable whether

Tasmanian VET should adopt the trend set in other states. There is a unique opportunity for

innovative and dynamic arrangements between the two sectors.

For Tasmania’s public VET sector, a strategic approach to the evolution of the tertiary sector in

Australia will be required, most profitably in conjunction with the University of Tasmania.

A Demand-Driven Higher Education Sector

The Bradley Review proposed targets for the growth of Higher Education:

•

•

By 2020, 40 per cent of 25 to 34-year-olds will have attained at least a bachelor-level

qualification

By 2020, 20 per cent of undergraduate enrolments in higher education should be students from

low socio-economic backgrounds. 14

To support this growth, it also recommended:

That the Australian Government introduce a demand-driven entitlement system for domestic higher

education students, in which recognised providers are free to enrol as many eligible students as they wish in

eligible higher education courses and receive corresponding government subsidies for those students.

(Recommendation 29) 15

This recommendation has come into full effect in 2012. As early as mid-January several universities

were reporting that enrolments were up by 10% with only first round offers released, 16 while the

Group of Eight universities 17 warned that standards might slip if entry scores are reduced too

much. 18

For Tasmania’s public VET sector, the potential lowering of Australian Tertiary Admission Rank

(ATAR) scores in response to student demand may impact on the upper level enrolments in VET

qualifications.

Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Reforms

On 13 April 2012, a revised National Agreement for Skills and Workforce Development and a

new National Partnership Agreement on Skills Reform was agreed to at the COAG meeting.

The reforms include:

•

•

the introduction of a national training entitlement

income contingent loans for government subsidised Diploma and Advanced Diploma programs

14

Bradley, D, op cit, p.xiii

Ibid, p.xxiii

16

Campus Review, 16 January 2012

17

The Group of Eight universities (Go8) is a coalition of Australia’s oldest, most research intensive and possible most

prestigious universities http://www.go8.edu.au/

18

http://theconversation.edu.au/university-standards-at-risk-from-low-performing-school-leavers-5697

15

20

•

•

•

•

developing and piloting independent validation of training provider assessments

strategies to enable TAFEs to operate effectively in an environment of greater competition

the development of a new MySkills website

supporting around 375,000 students nationally over five years to complete their qualifications. 19

The National Agreement for Skills and Workforce Development also specifically includes reference in

the reform directions to the role of public providers:

All Parties commit to pursuing the following reform directions, which include:

…

enable public providers to operate effectively in an environment of greater competition, recognising

their important function in servicing the training needs of industry, regions and local communities,

and their role that spans high level training and workforce development for industries and improved

skill and job outcomes for disadvantaged learners and communities; … 20

With implementation plans to be completed by 30 June 2012, the detailed implications of the

reforms for Tasmania are still to be finalised. Regardless of what is ultimately agreed to, Tasmania

will need to demonstrate that it is committed to the spirit of the Agreement and to reforms that will

lift the productivity of the economy.

For Tasmania’s public VET sector, responsiveness to national VET reforms will be critical to ensure the

state benefits from available Federal funding.

The Establishment of the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA)

ASQA came into effect on 1 July 2011 and Tasmania has referred its regulatory functions to this new

national body. A major impetus for the establishment of ASQA was concern about the quality and

consistency of the regulatory functions across the individual states and the need for considerably

improved rigour and transparency to restore full confidence in Australia’s VET system. This is

regarded as a pre-requisite for establishing a single tertiary regulatory body.

As ASQA becomes fully operational two major implications can be predicted for VET providers:

•

•

a more stringent and for some RTOs, possibly even onerous regulatory and audit regime

with the gradual move to a full cost recovery approach, increased fees for all aspects of ASQA’s

services.

This may mean that some existing RTOs review their RTO status and look to other ways to offer VET

programs, such as through merging with a larger RTO entity or auspicing. Some Tasmanian RTOs

have already indicated that they are considering their future options. The effects of this will become

evident over time.

For Tasmania’s public VET sector, structural arrangements to best meet compliance with national

VET standards are likely to evolve in the next two to three years.

19

20

Communique, 2012, COAG Meeting Canberra, 13 April 2012

National Agreement for Skills and Workforce Development, 2012, Council Of Australian Governments, section 25d, p.6

21

The Trade Training Centres Program

The Federal Government announced the Trade Training Centres program in 2008, providing

$2.5 billion over 10 years. Schools can apply for up to $1.5 million for new capital works, upgrading

of existing facilities and the purchase of industry standard equipment to extend options available to

secondary students from years 9-12 through access to VET. The aim is to improve Year 12 retention

rates, provide improved pathways into vocational careers and assist in addressing national skill

shortages. It is significant that the funding is only available to secondary schools and the stated

intention is for schools to offer up to Certificate III. It can thus be argued that the Trades Training

Centres program consolidates and affirms the role of schools and colleges in VET provision.

Tasmania already has six Trade Training Centres located on government school sites. These are at

George Town, Scottsdale, Bridgewater, Smithton, Huonville and St Helens/St Marys. Two further

Trade Training Centres were announced for Deloraine and Sorell/Triabunna in Round 4 of the

program at the end of 2011.

For Tasmania’s public sector, the Trade Training Centres program provides an important opportunity

to consolidate a network of state-of-the-art VET facilities for secondary level VET at strategic

locations across the state.

Roll-out of the National Broadband Network (NBN)

The communities of Smithton, Scottsdale and Midway Point were the first to receive optical fibre

broadband connections in the roll-out of NBN’s network in Tasmania 21. With seven out of the

twelve first release sites being in Tasmania and only five across the rest of mainland Australia,

Tasmania has potential to derive strategic advantage in the delivery of education and training from

its early access to broadband.

For public sector VET, the roll-out of the NBN presents opportunities to capitalise on the use of

e-learning and blended learning to improve access to education and training generally, to better

serve remote and rural communities and to provide more flexible training opportunities for

enterprises.

In summary, the above-mentioned trends and developments require that, in planning for the future

of public sector VET:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

21

provision needs to be highly competitive and relevant in the current economic climate

strong Higher Education linkages, which provide a potential mechanism to prosper in the

inbound international student market, may need to be further developed as well as

transnational education opportunities

a strategic approach to the evolution of the tertiary sector in Tasmania will be required, most

profitably in conjunction with the University of Tasmania

the potential lowering of ATAR scores in response to student demand may impact on the upper

level enrolments in VET qualifications

responsiveness to national VET reforms will be critical to ensure the state benefits from available

Federal funding

structural arrangements to best meet compliance with national VET standards are likely to

evolve in the next two to three years

the Trade Training Centres program provides an important opportunity to consolidate a network

of state-of-the-art VET facilities for secondary level VET at strategic locations across the state

NBNCo, 2010, Corporate Plan 2011-2013, p.69

22

•

the roll-out of the NBN presents opportunities to capitalise on the use of e-learning and blended

learning to improve access to education and training generally, to better serve remote and rural

communities and to provide more flexible training opportunities for enterprises.

3.4

The Wider VET Market

Tasmania’s public sector providers operate within a wider VET market with over 100 private RTOs

both local and from the mainland. Some of them offer a wide range of services while others operate

in niche areas. Many of them are small. These RTOs have continued to develop their business and

are adept at offering services where gaps in delivery emerge.

In its submission to the review, the Australian Council of Private Education and Training provided a

number of case studies of locally–based RTOs. Box 5 illustrates the development of one niche

market operator.

Box 5: Private RTOs in Niche Markets – Case Study 22

Seafood Training Tasmania

Tasmania is the largest producer of seafood with 2010 production values at (564m) together with a rapidly growing niche

aquaculture sector. In late 2009, Seafood Training Tasmania was approached by Australia’s second largest aquaculture

company, Huon Aquaculture Group, to help them with staffing and training for their new processing plant in North West

Tasmania. This involved a move of production from South East to North West Tasmania. Over the next few months, a

workforce plan was developed to support the flow of trained staff ready for employment when the new plant opened.

Working with a local ACC and group training company, 25 recently retrenched workers undertook a pre-apprenticeship

program and were offered employment at the plant. To meet the high export quality standards, Huon Aquaculture Group

signed the workers into a Certificate III in the Seafood Industry (Aquaculture traineeship). Today, 22 of the initial trainees

have completed the traineeship and remain employed in this specialist and niche market.

Case studies of two mainland RTOs currently operating in Tasmania are provided in Appendix 3.

These case studies are illustrative of the role that some of the private RTOs currently active in

Tasmania are playing. They form part of the wider market in which the public VET sector operates.

The numbers of these private RTOs are likely to increase as the COAG initiatives to promote

competition come to fruition.

22

Australian Council of Private Education and Training (ACPET) submission

23

4.

4.1

METHODOLOGY

Terms of Reference

Terms of Reference for the Review were developed in consultation with key stakeholders. They are

outlined in Box 6:

Box 6: Terms of Reference of the Review

1.

Review the current governance, funding and operational arrangements of the public providers of VET in

Tasmania and their capacity to improve student participation/retention, qualification and attainment rates

of Tasmanians as well as their ability to respond to identified skills needs and contribute to the productivity

of the state including the ability of the providers to:

• provide a broad range of VET options and pathways for all Tasmanians

• provide foundation and pre-employment, literacy and numeracy and work preparation courses for

those seeking pathways to higher level qualifications and work

• provide training and skills development for employees in enterprises in line with the enterprises’

current and future skill needs

• connect with higher education through Diplomas and Advanced Diplomas.

2.

Recommend and comment on options for future governance, funding and operational arrangements for

public providers of VET in Tasmania which clearly define the roles and responsibilities of provider(s) and

minimise the potential for competition between public providers.

3.

Take into account the COAG reform agenda as well as national agreements and strategic directions to

ensure recommended outcomes enable Tasmania to participate in and benefit from them.

4.

Investigate and advise on opportunities that exist with respect to higher education qualifications and

linkages between the public providers of VET and the university sector.

5.

Take into account the impact of any further change on the provision of VET for younger Tasmanians, and

ensure that the increased availability and accessibility of VET opportunities now available are not lost.

6.

Take into account issues of efficiency and effectiveness, being mindful of the current economic climate

including the capacity of the state budget to support the public VET providers.

7.

Take into account the ability of the system to implement further change both financially and in terms of the

impact on staff and students.

8.

Be informed by an analysis of national and international practise and experience. 23

4.2

Reference Group

A Reference Group of key stakeholders was appointed to act as a sounding board and an advisory

group to the process. Its role was to:

•

•

provide feedback to the independent consultant throughout the Review

ensure that the stakeholder group representatives were informed about the project progress

and had opportunities to provide feedback.

The Reference Group comprised of representatives from:

•

•

•

•

•

•

23

Tasmanian Skills Institute (TSI)

Tasmanian Polytechnic

Tasmanian Academy

Skills Tasmania

University of Tasmania (UTas)

Australian Education Union (AEU)

•

•

•

•

•

Community and Public Sector Union (CPSU)

United Voice

Tasmanian State School Parents and Friends

Tasmanian Principals Association

Tasmanian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (TCCI)

Consultation Paper, op cit, p.6

24

4.3

Approach Adopted

The approach adopted was determined by three key factors:

•

•

•

Time-lines: The Review was announced on 5 December 2011 with a completion date of

30 April 2012 and the prevailing view was there should be no undue delays or extensions.

Consensus: There was a perception that some of the previous changes had been imposed and

‘force-fitted’ into Tasmania with limited or no consultation and that this had negatively affected

the implementation. Reaching a level of consensus was therefore likely to be critical to success.

Unique Tasmanian circumstances: While there were potentially lessons to be learned from

interstate and international practice, a solution to address the unique Tasmanian circumstances

was seen to be a high priority.

Against this background, the approach outlined in Box 7 was designed to identify and build on the

consensus among stakeholders. Staged broadly to coincide with the three planned meetings of the

Reference Group, it involved identifying agreed Common Themes for the Review, re-stating these as

Principles for Change and translating these Principles into Proposals for Change.

Box 7: Approach Adopted for the Review

Reference

Group 3

(April 3)

Reference

Group 2

(March 5)

Reference

Group 1

(February 8)

Ongoing

4.4

1

•

•

•

2

•

•

•

3

•

•

•

4

•

•

•

PROPOSALS FOR CHANGE

Translating principles to actions

Specific proposals

Alignment with terms of reference

PRINCIPLES FOR CHANGE

Vision for the future

Underlying aims and objectives

Impact of change

BROAD LEVEL OF CONSENSUS

Extent of stakeholder agreement

Areas of ambiguity, disagreement

Identification of common themes

INFORMATION GATHERING

Analysis of data, research, literature

National/international practice

Stakeholder consultations, submissions

The Public Consultation Process

Underpinning this process, an extensive public consultation process was undertaken as the most

effective means to gauge the extent of consensus and any areas of potential contention.

Consultations took several forms:

•

•

Public Consultations: Nine public consultations were held across the state and were open to all

interested parties responding to public advertisements.

Student Consultations: A meeting with the consultant was arranged with current students from

both the Tasmanian Polytechnic and TSI at the Alanvale campus in Launceston. They

represented six different course areas across all years.

25

•

•

Industry Consultations: In conjunction with the Tasmanian Chamber of Commerce and Industry

(TCCI), three consultations were organised with mixed industry representatives. Other

consultations were held with industry peak bodies.

Other Consultations: Consultations were conducted with a range of peak bodies, agencies and

stakeholder bodies, some of which were at the request of these bodies.

The public consultations were deliberately unstructured with minimal input from the consultant so

as to enable maximum time for the participants’ priorities to be voiced. In all instances, each

individual present was offered the opportunity to make a statement and invited to address those

issues that were ‘front of mind’ in terms of what the Review should achieve. Following this process

and time permitting, there was an open forum.

Participants were also urged to use the more structured process of written submissions to address

matters of detail.

Details of the public consultations are contained in Appendix 4.

4.5

Written Submissions

Written submissions were called for at the outset of the process. A ‘Guide to Respondents’ was

included in the Consultation Paper released in December 2011 with a series of questions and issues

that respondents were invited to address. The closing date for submissions was set at

16 March 2012 to enable their full consideration before incorporation into this Report.

In all, 73 written submissions were received from some 41 organisations and 32 individuals, all of

which were of an exceptionally high standard.

The written submissions represent a wide range of organisations that have a stake in the VET sector

and include a cross-section of industry bodies. The names of organisations are identified when citing

extracts in this Report.

Many of the individual submissions were from current or former staff of the Tasmanian Polytechnic

and TSI but others were from parents and interested stakeholders. The identity of individual

respondents to the Review is not disclosed when citing extracts from their submissions in this

Report.

Details of the written submissions are contained in Appendix 5.

26

5.

CONSENSUS ACHIEVED

5.1

Common Themes (Stage 2 of the Methodology)

The Reference Group endorsed 20 Common Themes for the Review, which were aligned with the

Terms of Reference (TORs). These provided a useful framework for collating and synthesising the

input from the public consultations and the written submissions. The Common Themes therefore

inform this Report.

Theme 1 – Stakeholder Focus

TOR 1

The Review must achieve the best outcomes for students, employers and the future of the

Tasmanian economy.

Theme 2 – Public Sector VET

TOR 6

Given the circumstances in Tasmania, stable, quality and cost-effective public sector VET is critical,

both economically and socially.

Theme 3 – Coverage

TOR 2

For the purposes of the Review, public sector VET covers provision of AQF qualifications by publicly

funded RTOs which may occur in any of the following settings:

•

•

•

•

•

workplaces

post-secondary institutions (TAFE and Higher Education)

colleges and schools

Trade Training Centres

adult and community education providers.

Theme 4 – Elimination of Waste

TOR 6

The elimination of waste, duplication and unnecessary competition between the two main public

providers is urgent, so as to maximise investment in quality and improved outcomes.

Theme 5 – New Structures

The current structures are less than optimal.

Theme 6 – New Direction

Three years on, a return to TAFE Tasmania is not the optimal solution.

TOR 1/2

TOR 5

Theme 7 – Viability

TOR 1/6

Economies of scale and servicing of thin markets are critical considerations in the management of

VET in Tasmania and that streamlining of VET provision would improve viability and be manageable

by any national comparison.

Theme 8 – Brand Image

TOR 1

There is brand confusion within the sector which has had some negative effects on student,

employer/industry and community perception of VET in some cases.

Theme 9 – Higher Education Pathways

TOR 1/4

It is critical to further strengthen the linkages and pathways between VET and Higher Education.

27

Theme 10 – Cost Containment

TOR 6

A priority for the Review is to maximise the savings that will occur over time from the elimination of

waste, duplication and misdirected energy, not to incur additional costs.

Theme 11 – Corporate Services

TOR 6

Effective corporate services are critical for providers’ responsiveness and that the governance

arrangements need to ensure that the right balance between cost and control of these services is

found.

Theme 12 – Governance

Governance arrangements should:

•

•

TOR 1/2

ensure clear lines of accountability to government for performance and outcomes

provide a forum for industry to maximise flexibility, responsiveness and quality of provision.

Theme 13 – COAG Reforms

The outcomes of the Review must position Tasmania for the COAG reforms.

TOR 3

Theme 14 – Staff Resilience

TOR 7

The capacity for staff to cope with change is variable and well-managed change implementation

processes will be the deciding factor in this regard.

Theme 15 – Young Tasmanians

TOR 1/5

Improving participation and retention of young Tasmanians is a huge challenge. Learner support

and pastoral care issues must be considered across the range of VET settings, student types and

aspirations, taking into account the need to prepare learners for the requirements of the work

environment and for pathways to higher qualifications.

Theme 16 – Regionality

TOR 1

Given rural/remote and urban/metropolitan variations, a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach will not work.

Transport, accommodation and general access issues are significant impediments for both learners

and employers in rural areas.

Theme 17 – Vocational Currency

TOR 1

It is vital to achieve consistency of vocational currency of all VET teachers, 24 regardless of the setting.

Theme 18 – Professional Currency

TOR 1

Currency in the knowledge and practice of the VET teaching profession across the different settings

underpins the quality of VET provision.

Theme 19 – Recent Achievements

TOR 5

It is important to acknowledge the achievements of the past few years as well as to ensure they are

not lost as part of any change.

Theme 20 – Transparency of Funding

TOR 1/6

Funding issues could be simpler and clearer under more integrated arrangements. This includes

priority setting, funding allocation and reporting.

24

At least to the requirements of the AQTF/NVR

28

Box 8 provides a summary of the Common Themes.

Box 8: Summary of the Common Themes

FROM

FRAGMENTATION

COMPETITION

INCONSISTENCY

CONFUSION

DUPLICATION

PATCHINESS

WASTAGE

SYSTEM FOCUS

5.2

TO

INTEGRATION

COORDINATION

CONSISTENCY

CLARITY

STREAMLINING

QUALITY

COST-EFFECTIVENESS

LEARNER FOCUS

Principles for Change (Stage 3 of the Methodology)

Building on the Common Themes, the following Principles for Change were also endorsed by the

Reference Group:

Principle 1 – Seamlessness for learners

Entering and progressing on a quality VET pathway and beyond is as simple and seamless as possible

from a learner perspective.

Principle 2 – Responsiveness to industry

Industry’s expectations for the flexibility, relevance and quality of public sector VET are met.

Principle 3 – Focus on teaching and learning

In the first instance, getting the fundamentals of teaching, learning and assessment right is the

highest priority.

Principle 4 – Catering for different learner cohorts

The different needs of learners are identified and catered for, including those learning for the

purposes of their employment (productivity/work readiness) and those for gaining employment or

pursuing further study (participation/attainment).

Principle 5 – VET Practitioners (lecturers, teachers, instructors)

VET practitioners have fit-for-purpose skills, experience and qualifications for the areas in which they

work.

Principle 6 – Quality Facilities and Equipment

Every effort is made to ensure that all learners have access to the best available training facilities

and equipment.

Principle 7 – Efficiency

Stream-lined arrangements consistent with the size and financial capacity of Tasmania replace

duplication, unwarranted layers of management, waste and unnecessary competition.

Principle 8 – Public Sector Servicing

Operational and funding arrangements for servicing the public including catering for thin markets,

are clarified and publicised.

29

Principle 9 – Governance

Public sector VET delivery operates with a level of independence that enables it to be responsive,

flexible and competitive.

Principle 10 – Legislative Framework

All VET related activity is covered under one piece of contemporary and aspirational legislation that

ensures an integrated and efficient approach to the management and delivery of public sector VET.

Principle 11 – Branding and Marketing

Branding is clear and unambiguous for stakeholders and marketing is co-ordinated.

Principle 12 – Operational Arrangements

Operational arrangements and the associated processes and systems for the two major public

providers are fully integrated, including strategic planning, quality management, student

administration, staffing, professional development, funding and reporting.

Principle 13 – Implementing Change

The change management process is planned, transparent and fair and it occurs within a reasonable

timeframe.

5.3

Specific Proposals for Change (Stage 4 of the Methodology)

Finally, the Principles for Change developed in Stage 3 informed specific Proposals for Change, which

provide the structure for much of this Report. They were foreshadowed as follows:

Establish a renewed identity and image for VET in Tasmania.

Articulate a vision for the future of public sector VET in Tasmania.

Reform the legislative framework for VET so that all aspects of VET are covered by a single,

contemporary and aspirational piece of legislation, with a set of objects that provides a context

for all component parts to operate towards a common goal.

Create a single entity for the delivery of post-secondary VET in Tasmania that retains and builds

on the gains of the two existing entities over the past few years but takes this to a new level.

Formalise a network of secondary school and college VET providers (inclusive of the state’s

Trade Training Centres) to service the state with clear and manageable quality assurance

arrangements.

Capitalise on the potential VET/Higher Education partnership opportunities offered by the

presence of one university and one public sector VET provider in Tasmania.

Clarify the policy framework for adult and community education, clearly differentiating between

the activity which is VET related and that which is general or pre VET.

Develop measures to ensure a sustainable level of provision in rural and remote areas.

30

5.4

Commentary

The Common Themes, Principles for Change and Proposals for Change discussed and endorsed by

the Reference Group represent the key outputs of the Reference Group’s three meetings.

Noticeably there is strong alignment between these outputs and the views expressed during the

public consultations and in the written submissions.

From this perspective it can be concluded that the level of consensus on the directions of the Review

was high, providing a sound basis for the recommendations of this Report.

31

6.

6.1

VET IN TASMANIA – ITS IMAGE AND IDENTITY

Image and Identity

Consistent with Principles 3 and 8 outlined in Section 5 of this Report, the Review highlighted

concerns about the image and identity of VET in Tasmania. They are interrelated and can be

summarised loosely as a diffused identity and a damaged image.

Damaged Image

A perception that the image of VET has been damaged was prevalent in both the public

consultations and the written submissions. It was widely held that the status and reputation of VET

had suffered in the minds of employers and enterprises as well as students and parents. A number

of factors have contributed to this perception, including:

•

numerous examples of duplication and competition that left users of the system puzzled,

dismayed or even angry

some examples of poor practice in training delivery, typified by ‘tick and flick’ processes in

assessment

the impact of budgetary constraints on access to VET programs in some areas.

•

•

There was a considerable body of opinion that overall the reforms under ‘Tasmania Tomorrow’ had

not lived up to the expectations raised, and had perhaps even left Tasmania no better, or even

worse off, than it was prior to the changes. As it will take time to restore the image and status of

VET, this confirmed that it is imperative that the next set of changes is workable and broadly agreed.

Diffused Identity

Particularly during the public consultations it also became clear that the term VET is used very

loosely and inaccurately in some quarters, which may in turn reflect a damaged image. Examples of

where it was used inaccurately were in reference to:

•

taster programs or other introductory programs to the world of work conducted for year 9-10

students in schools

the operations of LINC Tasmania

leisure and lifestyle programs that may be offered in an adult education setting.

•

•

In none of these cases are nationally accredited outcomes involved. The accepted terminology in

Tasmania for programs at Year 10 level and below is Vocational Education and Learning (VEL)25 but

VEL does not necessarily exclude VET and the distinctions are not always clear in the wider

community. The operations of LINC Tasmania provide a welcoming and accessible gateway to VET,

but LINCs are not RTOs and any advancement towards accredited education and training outcomes

occurs through referral by LINC Tasmania staff to an RTO. Leisure and lifestyle programs are

essentially for personal interest and may or may not lead to the individual embarking on a VET

program.

Further, there was confusion about whether or not foundation programs such as literacy and

numeracy rightly belong within the province of VET with some maintaining that VET is only designed

to meet the direct needs of the labour market.

The Tasmanian Skills Strategy addresses this issue:

25

http://www.education.tas.gov.au/school/curriculum/guaranteeing-futures/vocation

32

“The Tasmanian Skills Strategy aspires to create an inclusive, fair, highly skilled and prosperous Tasmania

where:

•

•

•

•

Tasmanians have the skills to participate in a clever and connected community;

Together Tasmanians will overcome individual disadvantage and exclusion to increase participation;

Providers will partner with industry to deliver skills through high quality services; and

Employers will build workforce skills to innovate, invest and increase productivity.” 26

Importantly, the lack of clarity about what does and does not constitute VET has also led to

misconceptions about where funding is allocated and why, thus further blurring and often distorting

the image of the sector.

6.2

Definitions of VET

As a starting point, the Vocational Education and Training Act 1994 contains the authoritative

definition of VET:

vocational education and training means the education, training and attainment of qualifications or

statements of attainment under the vocational education and training provision of the Australian

Qualifications Framework. 27

The Act further specifies that:

Vocational education and training is to be –

• directed to the development of vocational competencies; and

• in preparation for, or directed to, the enhancement of opportunities to undertake vocational

education and training; and

• structured to incorporate principles of equal opportunity and fairness.

Vocational education and training includes –