Chapter 12 The Role of Fine Needle Aspiration Biopsy in the

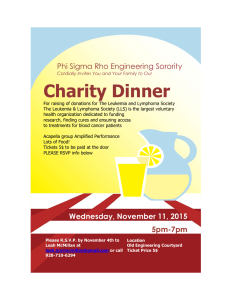

advertisement