Ladda PDF Lärdomsprov som heltext

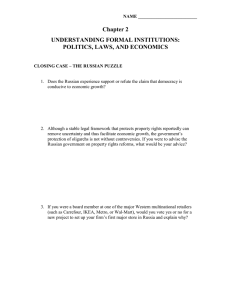

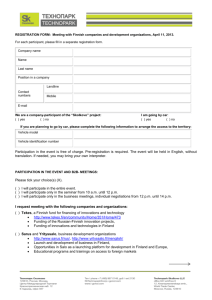

advertisement