GMP Toolbox: Understanding Good Manufacturing Practice

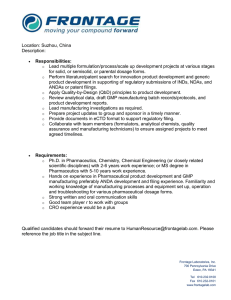

advertisement