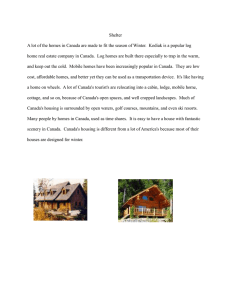

London Housing Design Guide Ñ

advertisement