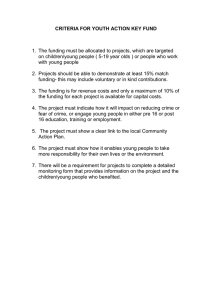

Designing out crime A designers` guide

advertisement