July-August 2014 | Volume 16 | Issue 72 www.noiseandhealth.org

advertisement

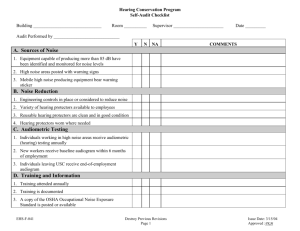

I ith & w SE d e A ex MB d In E, E N LI ED SC ISSN 1463-1741 Impact Factor® for 2012: 1.648 M Noise & Health • Volume 16 • Issue 72 • September-October 2014 • Pages 197-250 A Bi-monthly Inter-disciplinary International Journal www.noiseandhealth.org July-August 2014 | Volume 16 | Issue 72 A little bit less would be great: Adolescents’ opinion towards music levels Annick Gilles1,2, Inge Thuy1, Els De Rycke3, Paul Van de Heyning1,2 Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Antwerp University Hospital, Edegem, 2Department Translational Neuroscience, Faculty of Medicine, Campus Drie Eiken, Antwerp University, Wilrijk, 3Department of Human and Social Welfare, University College Ghent, Ghent, Belgium 1 Abstract Many music organizations are opposed to restrictive noise regulations, because of anxiety related to the possibility of a decrease in the number of adolescents attending music events. The present study consists of two research parts evaluating on one hand the youth’s attitudes toward the sound levels at indoor as well as outdoor musical activities and on the other hand the effect of more strict noise regulations on the party behavior of adolescents and young adults. In the first research part, an interview was conducted during a music event at a youth club. A total of 41 young adults were questioned concerning their opinion toward the intensity levels of the music twice: Once when the sound level was 98 dB(A), LAeq, 60min and once when the sound level was increased up to 103 dB(A), LAeq, 60min. Some additional questions concerning hearing protection (HP) use and attitudes toward more strict noise regulations were asked. In the second research part, an extended version of the questionnaire, with addition of some questions concerning the reasons for using/not using HP at music events, was published online and completed by 749 young adults. During the interview, 51% considered a level of 103 dB(A), LAeq, 60min too loud compared with 12% during a level of 98 dB(A), LAeq, 60min. For the other questions, the answers were similar for both research parts. Current sound levels at music venues were often considered as too loud. More than 80% held a positive attitude toward more strict noise regulations and reported that they would not alter their party behavior when the sound levels would decrease. The main reasons given for the low use of HP were that adolescents forget to use them, consider them as uncomfortable and that they never even thought about using them. These results suggest that adolescents do not demand excessive noise levels and that more strict noise regulation would not influence party behavior of youngsters. Keywords: Adolescents, attitude, hearing protection, noise legalization, questionnaire, recreational noise levels Introduction In modern society, adolescents and young adults are often exposed to loud music at social activities. Adolescents often attend indoor as well as outdoor music venues where sound levels easily reach 104-112 dB(A).[1] In addition, the use of personal listening devices of which maximum output levels often exceed safety barriers,[2-4] has become an established act in the daily lives of this group. As a consequence of increased recreational noise exposure, noise-induced hearing symptoms such as hearing loss, tinnitus, and hyperacusis have become more prevalent in Access this article online Quick Response Code: Website: www.noiseandhealth.org DOI: 10.4103/1463-1741.140508 PubMed ID: *** 285 the younger population.[5] One quarter of young people are weekly exposed to more than 85 dB(A) and the incidence of hearing symptoms seems to correlate with increased noise dose.[6] Tinnitus with a temporary character is experienced by 75% of adolescents and young adults after loud music exposure, usually disappearing within 2 h after noise exposure. Moreover, already 18% reports to perceive permanent tinnitus. Despite the high incidence of noiseinduced tinnitus, which is a clear sign of overexposure, this does not seem to be a motivator for the use of hearing protection (HP) as less than 5% of adolescents uses HP in noisy situations.[7,8] Despite the high prevalence of noiseinduced symptoms after recreational noise exposure, adolescents and young adults seem to have low awareness of the possible risks[8,9] and preventive campaigns have yielded only limited effects on the behavior of youngsters.[10] As a result, other preventive measures are required and there is clearly a growing need for sound level limitations during music venues, in order to protect people from suffering from hearing damage. In Flanders (the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium), such legislation is already well established Noise & Health, September-October 2014, Volume 16:72, 285-291 Gilles, et al.: Adolescents’ opinion towards loud music levels in an industrial environment and compulsory protective actions are required whenever workers are exposed to noise over 85 dB(A) for 8 h a day. For recreational noise environments, such legislation has been subject of debate for several years but since January 2013, the government also put forward new noise legislation for music venues, indoor as well as outdoor. A music organization can apply for an environmental license in three different categories. In category 1 a maximal intensity level of 85 dB(A) LAeq, 15min is permitted and sound measurements are not required in this category. In category 2 sound levels are greater than 85 dB(A) LAeq, 15min but may not exceed 95 dB(A) LAeq, 15min during the entire musical activity. Sound levels should be measured at a representative location and a clear visual indication of the sound levels to the person responsible for playing the music should be provided. Finally, in category 3 sound levels are higher than 95 dB(A) LAeq, 15min but may not exceed 100 dB(A) LAeq, 60min. This is the highest possible category where intensity levels may reach up to 100 dB(A) averaged over a period of 60 min. Output levels should be constantly measured and monitored during the entire music activity. Again a clear visual indication of the sound levels to the person responsible is required and withal, the free distribution of HP to the public is obliged. This legislation was not warmly received by many organizations of music venues, mainly because they feared a decrease of attendees due to lower sound levels. The current study contained two research parts. In the first part, which was conducted prior to the new noise regulations, a practical pilot study was performed exposing young people to sound levels below and above 100 dB(A) LAeq, 60min while asking for their opinions concerning the noise levels in both situations in order to reveal their opinions toward lower and higher sound levels at music venues. Previous research revealed that attitudes toward noise and the use of HP play a role in the actual behavior of using HP in noise situations.[8,11] However, the use of HP is very low considering the high prevalence of noise-induced symptoms. Therefore, the second research part, conducted in February 2013, consisted of an online questionnaire assessing noise-induced symptoms, the attitudes toward more strict noise regulations, frequency of attendance at open air and indoor musical events, and the reasons why adolescents and young adults do (not) use HP in noisy situations. Methods Research part 1 The study was conducted in a youth club in November 2012, thus prior to the noise legislation. The owner of the youth club was well informed as well as the regular in-house DJ who cooperated in the study. Forty-one young adults of which 26 were females and 15 were males, voluntarily participated in the study (mean age = 19.2 years, standard deviation [SD] = 2.1 years). The DJ was asked to keep the Noise & Health, September-October 2014, Volume 16 volume below 100 dB(A) LAeq, 60min for 2 consecutive hours. Output levels were measured at a referential place (middle of the room) by use of a portable dosimeter (Casella USA, dBadge Micro Noise Dosimeter Kit) and a level of 98 dB(A) LAeq, 60min was registered. After that the DJ was told to play music at the level he usually does at this particular youth club. Sound levels were again measured and a noise level of 103 dB(A) LAeq, 60min was registered. At the beginning of the evening, all participants underwent a short interview performed by the same interviewer. First, it was assessed whether they had knowledge of the new noise legislation (yes-no) and whether they were positive, negative or neutral toward such a measure. In accordance with Weichbold and Zorowka (2005) it was asked what the opinion of the adolescents was concerning the intensity levels at discotheques.[12] The answer possibilities were (a) noise levels should be raised, (b) noise levels should be lowered and (c) noise levels should stay the same. In addition, it was assessed whether, in case of a slight decrease of intensity levels at music events, adolescents would go out (a) more often, (b) as often as now and (c) somewhere else where the noise levels are higher. Furthermore, when assessing HP use, one had to confirm one of following sentences: ‘I usually wear HP’, or ‘I usually do not wear HP’. In case when adolescents used HP they had to report whether it was universal HP or custom made HP. After approximately 30 min, the participants were asked whether they considered the current noise levels (98 dB(A) LAeq, 60min) (a) too loud, (b) too quiet or (c) perfect. After the volume was raised to 103 dB(A) LAeq, 60min the adolescents were asked the same question a second time. Research part 2 During the month of February 2013, an online questionnaire was filled out by 749 adolescents and young adults (age range = 13-25 years old; mean age = 19 years old, SD = 3 years) of which 198 male and 551 female participants. In order to reach as much as young people as possible, the link to the questionnaire was published online and promoted on social media such as Facebook. In addition, 10 high schools and five colleges cooperated in the study and published the link to the questionnaire on their official websites. A first section concerned the frequency of attendance at musical events. For all questions a distinction between indoor (e.g., youth club, night club) and outdoor (e.g., festival) activities was made. The frequency of attendance for both categories was questioned as well as the opinion toward the current intensity levels at such events. In addition, it was questioned how often they experienced following symptoms after recreational noise exposure: Hearing loss, “stuffy ears”, tinnitus, balance problems, ear pain, and hyperacusis. Answer possibilities were always (100%), often (75%), sometimes (50%), seldom (25%) and never (0%). In accordance with the previous research part, it was assessed whether one was aware that new noise legislation came into force. Irrespective of the 286 Gilles, et al.: Adolescents’ opinion towards loud music levels answer to the latter question, it was asked whether one was positive or negative toward this new regulation. In addition, one had to indicate a top three (1 = main reason) of reasons why one held a positive or a negative attitude toward the noise legislation. The next question was also similar to one in the previous research part: “Now we have more strict noise regulations, how often would you go to a youth club or night club?” The same question was asked for outdoor musical activities. Answer possibilities were: a. I would go out less, b. I would go out as often as before, c. I would go out more often. The second section of the questionnaire concerned the use of HP in adolescents and young adults. First was evaluated how often (always [100%], often [75%], sometimes [50%], seldom [25%] and never [0%]) one used HP in noisy environments where again a distinction was made for indoor and outdoor activities and whether one used HP of the universal type or custom made. When one indicated not to use HP, a list of possible reasons was given and one had to select a top three of reasons why one does not use HP. In the opposite case, one had to select a top three why one does use HP. The given reasons for using/not using HP are depicted in Figures 1 and 2. Results Research part 1 The answers of all participants during the interview are listed in Table 1. Almost half of the students were informed that new noise legislation would be in force in the future. Most students reported to be satisfied with the current noise levels in discotheques (in November 2012). However, more than 70% held a positive attitude toward a more restrictive measure. Eight out of the 41 students usually uses HP. Nevertheless, at the time of the interview, only four students actually wore HP. Figure 1 illustrates the opinion towards the noise levels at the music venue. During the first 2 h a noise level of 98 dB(A) LAeq, 60min was measured. At that time, 85.4% of the students considered the noise levels as “perfect”, 12.2% thought the music was “too loud” and 2.4% thought it was “too quiet”. When the noise level was raised to 103 dB(A) LAeq, 60min and students were asked for their opinion again, only 48% still thought the noise level was “perfect” and 51% now considered the music as “too loud”. Research part 2 Table 2 provides all answers of the respondents. The visiting rate of discotheques was quite high as 42% regularly (every 2 weeks or more) attend in night clubs. More than half of the students (55.3%) rated the noise levels at these occasions as too loud and the other half (43.4%) thought that the levels should remain the same. Slightly other results were seen for festivals and open air activities. First, the attendance of festivals is much Table 1: Answers of the 41 participants during the interview Questionnaire item Informed about new noise regulation Yes No Opinion toward new noise regulation Negative Positive No opinion Opinion discotheque levels Should be raised Should be lowered Should stay the same Party behavior after more strict regulation Would go out more often Would go out as often as now Would go somewhere else where the noise levels are higher Use of HP I usually wear HP I usually do not wear HP % (n = total of participants) 43.9 (18) 56.1 (23) 19.5 (8) 70.7 (29) 9.8 (4) 4.9 (2) 24.4 (10) 70.7 (29) 4.9 (2) 90.2 (37) 4.9 (2) 19.5 (8) 80.5 (33) HP = Hearing protection Figure 1: Opinion toward the noise levels of 41 young adults during a music event at a youth club 287 Figure 2: Frequency of reasons given for using hearing protection among 749 adolescents and young adults Noise & Health, September-October 2014, Volume 16 Gilles, et al.: Adolescents’ opinion towards loud music levels Table 2: Reponses of 749 adolescents and young adults on the online questionnaire Questionnaire items % (n = total of participants) Frequency youth club, party hall or discotheque attendance 1× a week >1× a week Every 2 weeks Monthly Less than monthly Frequency festival/open air activity <1× during season 1× during season 2× during season 3× during season 4× during season 5× during season >5× during season Opinion youth club, party hall and discotheque noise levels Should be raised Should be lowered Should stay the same Opinion festival/open air activity noise levels Should be raised Should be lowered Should stay the same Informed about new noise legislation Yes No Opinion towards new noise legislation Negative Positive Party behavior after more strict regulation (discotheque) Would go out more often Would go out as often as now Would go out somewhere else where the noise levels are higher Party behavior after more strict regulation (festival) Would go out more often Would go out as often as now Would go out somewhere else where the noise levels are higher Frequency of hearing protection use (disco) (%) Always (100) Often (75) Sometimes (50) Seldom (25) Never (0) Frequency of hearing protection use (festival) (%) Always (100) Often (75) Sometimes (50) Seldom (25) Never (0) Type hearing protection Universal Custom made Noise & Health, September-October 2014, Volume 16 21.2 (159) 8.8 (66) 12.1 (91) 20.7 (155) 37.1 (278) 34.3 (257) 24.4 (183) 20.2 (151) 12.3 (92) 3.5 (26) 1.5 (11) 3.9 (29) 1.3 (10) 55.3 (414) 43.4 (325) 3.3 (25) 35.4 (265) 61.3 (459) 45.9 (344) 54.1 (405) 18 (134) 82 (612) 8.8 (66) 85.7 (642) 5.5 (41) 8.5 (64) 83.6 (626) 7.9 (59) lower as most students only visit one festival during the summer period. In addition, the noise levels are rated more comfortable as 61% says that the noise levels should remain the same. As shown in Table 3, the prevalence of noiseinduced symptoms at indoor as well as outdoor musical events is quite high, especially when looking at tinnitus, hearing loss and “stuffy ears”. In addition, approximately half of the respondents had knowledge concerning the new noise legislation and 82% held a positive attitude toward a more strict noise regulation. Furthermore, the lowering of noise levels at musical venues, indoor as well as outdoor activities would not change the party behavior of adolescents and 85.7% would go out as much as now. Interestingly, a high rate of HP use was found as 11.9% always uses HP at night clubs and even 20% uses HP at festivals. Figure 2 illustrates adolescents’ reasons for using HP. Looking at the most chosen primary reasons the main three reasons were: 1. To prevent noise-induced hearing symptoms; 2. I think it is important to protect my hearing; 3. The music is often too loud. The most chosen primary reasons for not using HP, as illustrated in Figure 3, were: 1. I never thought about using it; 2. I am seldom in noisy situations; 3. I forget to use it. In addition, a fourth important reason is that HP is considered as uncomfortable by many adolescents. Discussion and Conclusions The question whether sound levels at music venues should be lowered has been under debate for quite a time. The present study, assessing adolescents’ opinion towards music noise levels at social activities, showed that adolescents and young adults do not necessarily require such excessive noise levels as Mercier and Hohmann (2002) also previously stated.[13] The present study also 11.9 (89) 13.2 (99) 10.1 (76) 7.5 (56) 57.3 (429) 20.3 (152) 15.6 (117) 6.4 (48) 3.3 (25) 54.3 (407) 82 (287) 18 (63) Figure 3: Frequency of reasons given for not using hearing protection among 749 adolescents and young adults 288 Gilles, et al.: Adolescents’ opinion towards loud music levels Table 3: frequency of noise-induced hearing symptoms after recreational noise exposure in 749 adolescents and young adults Experience of noiseinduced symptoms Youth club/party hall/discotheque Hearing loss “Stuffy ears” Tinnitus Imbalance Ear pain Hyperacusis Festival/open air activity Hearing loss “Stuffy ears” Tinnitus Imbalance Ear pain Hyperacusis Always (100%) Often Sometimes Seldom Never (75%) (50%) (25%) (0%) 3.5 6.8 14.8 0.8 1.3 3.9 11.1 21.0 21.4 0.9 4.1 7.9 19.6 24.0 25.8 6.7 14.4 14.3 31.4 24.8 24.3 11.1 23.2 21.6 34.4 23.4 13.8 80.5 56.9 52.3 3.2 3.2 9.1 0.9 1.2 3.1 6.5 10.1 13.0 0.9 3.2 4.8 14.6 19.9 21.0 5.1 10.9 11.2 27.5 28.7 26.3 10.4 20.0 20.2 48.2 38.1 30.7 82.6 64.6 60.7 found that most young people show a positive attitude toward a more strict noise regulation and that their party behavior would not be altered by such measure. Moreover, it appears that many young people often consider the sound levels as too loud, while going out. In the first research part, approximately 86% of the participants considered 98 dB(A) LAeq, 60min as a perfect intensity level during a party. When the noise level was raised up to 103 dB(A) LAeq, 60min, half of the students considered this level as too loud. Nevertheless, 49% still rated such a loud level, which may cause serious hearing damage after prolonged exposition, as “perfect”. Adolescents’ attitudes toward noise may account for this perception. Most adolescents and young adults have positive or neutral attitudes toward loud noise exposure, which means they do not see loud music as something dangerous, but rather as something “normal” in today’s society.[8,14-16] Many adolescents and young adults often perceive noise-induced symptoms such as tinnitus after loud music exposure, but most do not consider this as “alarming” and think they would not develop hearing loss until at a later age.[17] One possible way to alter such perceptions toward loud music is preventive campaigns focusing on the risks of highly amplified music.[18] Previous research has revealed that the model of the theory of planned behavior might provide a theoretical framework to predict and alter human health behavior.[11] According to this model, by use of preventive campaigns, attitudes toward noise and HP can be altered resulting into an increase of HP use.[19] The authors would like to remark that the order of the intensity of music presentation in the present study might influence the opinion towards the sound levels. As such, also the opposite presentation- first 103 dB(A) LAeq, 60min and afterwards 98 dB(A) LAeq, 60min- should have been performed, but this idea was not supported by the DJ. In 289 addition, this part of the study comprised the participation of only 41 subjects. As a result, interpretations should be made with caution. However, in the second research part, a survey was posted online reaching 749 young people showing that also in this group half of the respondents were familiar with the new noise legislation and 82% had a positive attitude toward such a measure. In this population almost 55% reported the sound levels at discotheques as too loud whereas only 35% thought the same of festivals. In accordance to the first research part, 85% reported that their party behavior would not be altered as a result of more strict noise regulations. The fact that adolescents support more strict noise regulations, which intend to protect their hearing, evokes some confusion. Despite of previous studies finding that the majority of adolescents are well aware of the possibly damaging risks of loud music exposure[7,17] the use of HP has been proven to be very low nonetheless.[7,8,16,20] Such findings are surprising considering the high prevalence of noise-induced symptoms such as tinnitus, hearing loss and hyperacusis after leisure noise exposure.[8,21-23] In the present study, the use of HP was almost double as high at outdoor activities such as festivals (20.3% always uses HP) compared with indoor activities such as discotheques (11.9% always uses HP). Such a distinction between indoor and outdoor activities was also made by Widén et al. (2009), but the use of HP was much lower compared with the present study as there was 3% of the participants using HP at open air festivals/ concerts and 0% used HP at youth clubs/discotheques. There are probably multiple reasons for these differing findings. First, it is possible that attitudes toward noise and HP differ between countries because of cultural and social factors. For example, Widén et al. (2006) compared the use of HP in Swedish and US young adults aged 17-21 years old. Swedish students were almost 13 times more likely to use HP at concerts compared to US students (61.2% of the Swedish students used HP compared with 9.5% of the US students).[24] However, this difference was more due to the difference in attitudes towards noise and especially toward elements concerning youth culture (such as sound levels at discotheques) and not to the variable “country”. [24] Second, the timing of interrogating adolescents may be a very crucial factor as the attitudes toward noise and HP are probably subject to temporary factors such as preventive campaigns. In the case of Widén et al. (2006), preventive campaigns focusing on the risks of hearing damage caused by loud music exposure preceded the study where in the US such campaigns have been mainly targeting industrial environments. Recently in Belgium, similar results were found as the use of HP increased fourfold after an informational campaign.[19] However, the long-term effects of such behavioral changes are unknown and it is well possible that the use of HP returns to baseline in the absence of preventive campaigns presented on a regular basis. Nevertheless, the present study also focused on the reasons why or why not young people use HP in Noise & Health, September-October 2014, Volume 16 Gilles, et al.: Adolescents’ opinion towards loud music levels noisy situations. The reasons for not using HP are quite similar to those found by Crandell et al. (2004) who also found that HP is mainly seen as inconvenient, one forgets to use it and many never even thought about it.[20] The fact that HP is often considered as uncomfortable probably has multiple reasons. Most often universal HP is used, which is assumed to fit for everyone. However, in smaller ear canals the HP does not fit which might cause discomfort as a result of pressure and occlusion of the ear canal. On the contrary, in larger ear canals the HP will not stay in place and the ear plugs tend to fall out, which also causes discomfort and the need for frequent reinsertion may lead to the cessation of HP use. Properly made custom HPs can reduce discomfort in many cases. In addition, some individuals may benefit from special musician’s earplugs that include special filters, which can maintain the music quality as opposed to universal HPs, which might distort sounds.[25] Address for correspondence: Dr. Annick Gilles, Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Antwerp University Hospital, Wilrijkstraat 10, Edegem 2650, Belgium. E-mail: annick.gilles@uza.be References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Some extra information was found by also asking why one does use HP. Although the main reason was to prevent noise-induced hearing damage, it was also clear that many students used HP because they already experienced noise damage in the form of hearing loss, tinnitus or hyperacusis and they want to prevent further damage. As shown in Table 3, temporary noise-induced hearing symptoms are quite prevalent after recreational noise exposure. These findings hold useful information for future preventive campaigns, which should not only focus on the long-term effects of recreational noise but should more carefully consider the short term symptoms such as hearing loss, tinnitus and hyperacusis in order to make young people more aware of the risks. As temporary symptoms are often seen as a “normal” condition after noise exposition by adolescents,[8] future campaigns should underline the importance of temporary symptoms as a warning signal for possible permanent damage. Demonstration of a high-pitched sound (which is usually the tinnitus pitch heard after noise exposure) in educational environments may make more people aware of the fact that tinnitus (also in its temporary form) is a sign of overexposure, which may not recover some day. To date, it is unclear, which strategy is most suitable in order to prevent noiseinduced damage in adolescents. The free distribution of HP, which is obliged for venues originating in category 3 and the display of sound levels visible to the public with information on the risks of amplified music might incline more people to use HP. Venues should invest in acoustic material when required in order to meet the criteria of the new noise legislation and the government should adopt a cautious and strict approach in case of any violation. Rawool (2012) described several strategies for reducing noise exposure at music venues.[26] Presumably, a combination of strategies is necessary in order to limit noise-induced damage in adolescents but further research is required. Noise & Health, September-October 2014, Volume 16 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. Serra MR, Biassoni EC, Richter U, Minoldo G, Franco G, Abraham S, et al. Recreational noise exposure and its effects on the hearing of adolescents. Part I: An interdisciplinary long-term study. Int J Audiol 2005;44:65-73. Fligor BJ, Cox LC. Output levels of commercially available portable compact disc players and the potential risk to hearing. Ear Hear 2004;25:513-27. Portnuff CD, Fligor BJ, Arehart KH. Teenage use of portable listening devices: A hazard to hearing? J Am Acad Audiol 2011;22:663-77. Peng JH, Tao ZZ, Huang ZW. Risk of damage to hearing from personal listening devices in young adults. J Otolaryngol 2007;36:181-5. Henderson E, Testa MA, Hartnick C. Prevalence of noise-induced hearing-threshold shifts and hearing loss among US youths. Pediatrics 2011;127:e39-46. Jokitulppo J, Toivonen M, Björk E. Estimated leisure-time noise exposure, hearing thresholds, and hearing symptoms of Finnish conscripts. Mil Med 2006;171:112-6. Gilles A, De Ridder D, Van Hal G, Wouters K, Kleine Punte A, Van de Heyning P. Prevalence of leisure noise-induced tinnitus and the attitude toward noise in university students. Otol Neurotol 2012;33:899-906. Gilles A, Van Hal G, De Ridder D, Wouters K, Van de Heyning P. Epidemiology of noise-induced tinnitus and the attitudes and beliefs towards noise and hearing protection in adolescents. PLoS One 2013;8:e70297. Muchnik C, Amir N, Shabtai E, Kaplan-Neeman R. Preferred listening levels of personal listening devices in young teenagers: Self reports and physical measurements. Int J Audiol 2012;51:287-93. Weichbold V, Zorowka P. Can a hearing education campaign for adolescents change their music listening behavior? Int J Audiol 2007;46:128-33. Widén SE. A suggested model for decision-making regarding hearing conservation: Towards a systems theory approach. Int J Audiol 2013;52:57-64. Weichbold V, Zorowka P. Will adolescents visit discotheque less often if sound levels of music are decreased? HNO 2005;53:845-8, 850. Mercier V, Hohmann BW. Is electronically amplified music too loud? What do young people think? Noise Health 2002;4:47-55. Landälv D, Malmström L, Widén SE. Adolescents’ reported hearing symptoms and attitudes toward loud music. Noise Health 2013;15:347-54. Holmes AE, Widén SE, Erlandsson S, Carver CL, White LL. Perceived hearing status and attitudes toward noise in young adults. Am J Audiol 2007;16:S182-9. Widén SE, Holmes AE, Johnson T, Bohlin M, Erlandsson SI. Hearing, use of hearing protection, and attitudes towards noise among young American adults. Int J Audiol 2009;48:537-45. Rawool VW, Colligon-Wayne LA. Auditory lifestyles and beliefs related to hearing loss among college students in the USA. Noise Health 2008;10:1-10. Bohlin MC, Erlandsson SI. Risk behaviour and noise exposure among adolescents. Noise Health 2007;9:55-63. Gilles A, Paul Vde H. Effectiveness of a preventive campaign for noiseinduced hearing damage in adolescents. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2014;78:604-9. Crandell C, Mills TL, Gauthier R. Knowledge, behaviors, and attitudes about hearing loss and hearing protection among racial/ethnically diverse young adults. J Natl Med Assoc 2004;96:176-86. 290 Gilles, et al.: Adolescents’ opinion towards loud music levels 21. Chung JH, Des Roches CM, Meunier J, Eavey RD. Evaluation of noise-induced hearing loss in young people using a web-based survey technique. Pediatrics 2005;115:861-7. 22. Quintanilla-Dieck Mde L, Artunduaga MA, Eavey RD. Intentional exposure to loud music: The second MTV.com survey reveals an opportunity to educate. J Pediatr 2009;155:550-5. 23. Jokitulppo JS, Björk EA, Akaan-Penttilä E. Estimated leisure noise exposure and hearing symptoms in Finnish teenagers. Scand Audiol 1997;26:257-62. 24. Widén SE, Holmes AE, Erlandsson SI. Reported hearing protection use in young adults from Sweden and the USA: Effects of attitude and gender. Int J Audiol 2006;45:273-80. 25. Rawool VW. Conservation and Management of Hearing Loss in 291 Musicians. Hearing Conservation: In Occupational, Recreational, Educational and Home Settings. New York: Thieme; 2012. p. 201-23. 26. Rawool VW. Noise Control and Hearing Conservation in Nonoccupational Settings. Hearing Conservation: In Occupational, Recreational, Educational and Home Settings. New York: Thieme; 2012. p. 224-41. How to cite this article: Gilles A, Thuy I, De Rycke E, de Heyning PV. A little bit less would be great: Adolescents’ opinion towards music levels. Noise Health 2014;16:285-91. Source of Support: Nil, Conflict of Interest: None declared. Noise & Health, September-October 2014, Volume 16