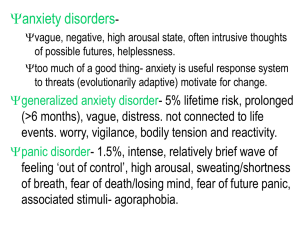

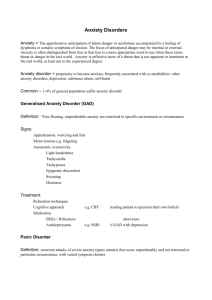

Panic Disorder Generalised Anxiety Disorder and

advertisement