8B Archaeological Landscape Report

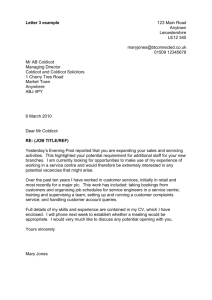

advertisement

An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) Patrick Clay and Paul Courtney ULAS Report No. 2011-150 © ULAS 2011 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) Patrick Clay and Paul Courtney for Hallam Land Management P.A 11/0100/1/OX Checked by Project Manager Signed:. Date: 03.10.2011 Name: Patrick Clay University of Leicester Archaeological Services University Rd., Leicester, LE1 7RH Tel: (0116) 252 2848 Fax: (0116) 2522614 ULAS Report No. 2011-150 ©2011 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) CONTENTS 1.Summary ................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 3. Aims and Objectives .............................................................................................................. 1 4. Assumptions........................................................................................................................... 2 5. Sources ................................................................................................................................... 2 6. Site Location, Geology and Topography ............................................................................... 2 7. Part 1 Landscape History: Prehistoric-Anglo-Saxon ........................................................ 3 7.1. Palaeolithic (with Lynden Cooper) ......................................................................... 3 7.2 Mesolithic c. 9700-6,000 years ago ............................................................................ 4 7.3 Earlier Neolithic c. 4,000-2500BC ............................................................................. 4 7.4 Later Neolithic – Earlier Bronze Age c. 2500- 1000BC ............................................ 5 7.5 Later Bronze Age - Iron Age c. 1000 BC - AD 43 ..................................................... 6 7.6 Roman AD 43-450 ...................................................................................................... 6 7.7 Anglo-Saxon 450-850 .................................................................................................. 7 8. Part 2 Landscape History: Medieval-post-medieval by Paul Courtney ........................... 7 8.1 Brief ............................................................................................................................. 7 8.2 Sources ........................................................................................................................ 7 8.3 Descent of Manor ........................................................................................................ 8 8.4 Problems of sources .................................................................................................. 10 8.5 Medieval Landscape .................................................................................................. 10 8.6 Topographic Features of the Forest in Lubbersthorpe ............................................. 13 8.7 Archaeologically Sensitive Sites in the Historic Landscape (i.e c. AD 1000-present) ……………………………………………………………………………………...14 9. Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... 14 10. References ..................................................................................................................... 15 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1 Application Area with features referred to in the text …………………………..19 Figure 2 1796 engraving of the chapel shows it as in ruins immediately adjacent to the manor complex, probably to the north-west of the main Abbey Farmhouse (from Nichols 1815, 4i, pl. XII)……………………………………………………………………………………..20 Figure 3 Plan of Lubbesthorpe village earthworks (left) and fishpond (see Fig 1.7). From Hartley 1989 Fig. 65……………………………………………………………………….20 Figure 1: Plan of ridge and furrow in the area derived from aerial photography with approx limit of application area outlined. From Hartley 1989 p. 77………………………………21 © ULAS 2011 ii Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) Patrick Clay and Paul Courtney 1.Summary An Archaeological landscape assessment has been prepared by University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) for Hallam Land Management covering land at the ‘Drummond Estate’, which lies in the parishes of Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, in advance of proposed development of the area. The site covers around 380 hectares between Leicester Forest East and Enderby and lies adjacent to the M1 and the M69. The area currently consists of farmland. The landscape assessment has been prepared to supplement the desk-based assessment (Hunt 2008) and suggests how the area has developed over time from the Palaeolithic to the modern periods. 2. Introduction This document is an archaeological assessment of the landscape history for land at the proposed New Lubbesthorpe site, which lies between Leicester Forest East and Enderby, close to the western edge of the M1 motorway within the parishes of Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (National Grid References SK 50 & SP 59; centre-point SK 535 014 Figure 1). The assessment has been commissioned from University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) by Davidsons, Hallam Land Management and Barratt Homes in advance of development proposals for the site. The archaeological assessment has been commissioned as a response to comments from the planning authority, Blaby District Council, their advisors on the Historic Environment, Leicestershire County Council and English Heritage. Further information of the archaeological potential in the form of an assessment of the landscape history of the area was felt to be necessary to assist BDC in making a planning decision. The area includes a number of archaeological sites, including the deserted medieval village (DMV) of Lubbesthorpe (MLE216), which is also a Scheduled Monument (SM30274). There are also several archaeological sites of importance in the vicinity of the assessment area (Hunt 2008). 3. Aims and Objectives The aim of the study is to provide an assessment of how the landscape has developed from the Palaeolithic to the modern period, within the context of the East Midlands (Cooper ed 2006). It is to include an assessment of the areas significance in contributing to the study of the archaeology of the East Midlands over time. The assessment should, once the information has been synthesised, assist in providing an informed planning decision. © ULAS 2011 1 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) All work follows the Institute for Archaeologist’s Code of Conduct and adheres to their Standard and Guidance for Archaeological Desk-based Assessments. 4. Assumptions All work has been carried out based on plans supplied by the client. The archaeological resource is by its nature an incomplete record. Where there are significant alluvial/colluvial deposits, made ground or a lack of previous archaeological fieldwork, archaeological remains can remain undetected. 5. Sources The following sources have been consulted to assess previous land use and archaeological potential: • Archaeological records (Historic Environment Record for Leicestershire and Rutland (HER), Leicestershire County Council). • Previous Ordnance Survey and other maps of the area (Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland). • Geological maps (ULAS Reference Library). • Historical background material (ULAS Reference Library and University of Leicester Library). • Historic Landscape Characterisation Project for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland (Leicestershire County Council Community Services: Historic and Natural Environment). The period divisions used in this document follow those used in L. Cooper 2004 and N. Cooper (ed) 2006. 6. Site Location, Geology and Topography The site covers an area of around 380 hectares to the west of the M1 motorway, to the south of Leicester Forest East and to the north of Enderby. The area largely consists of farmland and includes several groups of farm buildings, roads and access tracks and small wooded areas. It is a typical sample of East Midlands lowland clayland landscape showing evidence of successful agricultural exploitation over many centuries and is made up of farmland, both arable and pasture with small parcels of woodland, between which are trackways and footpaths. It is essentially an area of plough zone although pastoral use has led the preservation of some earthwork remains including the scheduled monument of Lubbesthorpe Deserted Medieval Village (DMV) and associated field systems (Figure 1). The area covers c. 380 hectares and is broadly bounded by the M1 motorway to the east, Leicester Lane, Enderby to the south, by part of Beggars Lane to the west and by Leicester Forest East to the north. Junction 21 of the M1 lies at the south-east corner of this area and the area is located within the parishes of Lubbesthorpe and Leicester Forest East. The area contains four farms: Abbey Farm, Hopyard Farm, New House Farm and Old Warren Farm and there are some building remains at Old House, which lies close to the western edge of the site. The DMV of Lubbesthorpe, which includes visible earthworks, is located close to the south-eastern extent of the area, near Hopyard Farm and Abbey Farm. The land here is quite undulating but broadly falls from north to south, from between 95m OD and 75m OD. The geology of the area, according to the Ordnance Survey Geological © ULAS 2011 2 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) Survey of Great Britain Sheet 156, is likely to consist of alluvium and river gravels overlying glacial till (boulder clay) and Mercia Mudstone. 7. Part 1. Landscape History: Prehistoric-Anglo-Saxon 7.1. Palaeolithic (with Lynden Cooper) The Palaeolithic, covering the last 900,000 years, has recently seen a resurgence of research and enormous progress has been made in our understanding of this very long time span with the identification of when there may have been potential occupation during cool transitional periods (McNab 2006). There are no Palaeolithic implements recorded on the HER from the area although this does not necessarily preclude their presence as their recognition in the field has only developed recently. (NB This has been confirmed during ongoing trial trenching in the south-east of the application area where two surface finds of this period have been recovered (W. Jarvis pers. comm.)). 7.1.1 Lower Palaeolithic (c. 900,000-250,000 years ago) Most of the geology of the area comprising Mercia Mudstone Group deposits and glacial drift is not conducive to the survival of in-situ deposits where Lower Palaeolithic material may be present. The survival of Lower Palaeolithic implements in secondary contexts, however, is possible. From the earliest (pre-Anglian deposits) no East Midlands sediments have as yet been known to contain archaeology, even though the potential for Bytham river sediments is high. Over 100 Lower Palaeolithic implements have been recovered from on-going quarrying in Brooksby; although to date their context is not known, there have been two recent in-situ discoveries (August 2011). Bytham river sediments pass under Leicester and although the application area is close to the projected Bytham river course the key deposits comprising the Brooksby group of sediments underlying the Bytham Baginton Formation sediments are not present. The south-east of the area comprises Glaciofluvial deposits consisting of brown to red-brown sands and gravels. These are likely to be glacial outwash of Anglian date and at the height of the Anglian, Britain would almost certainly have been uninhabitable (McNabb 2006, 20). While there is unlikely to be any in-situ archaeological deposits it may contain residual artefacts from the Cromerian. There is therefore no potential for any in-situ heritage assets and low potential for a residual chance find from this period to be present within the application area. 7.1.2 The Middle Palaeolithic (c. 250,000-40,000 years ago) For most of the Middle Palaeolithic the area would have been covered by ice and been uninhabitable. The following warm period the Ipswichian led to tropical climate in Britain with a rich fauna including hippopotamus, elephant and rhinocerous. Curiously however human occupation appears to be absent in Britain until colonisation around 58,000 years ago by Neanderthals. The few lithic assemblages of this date are similar to the Mousterian of France and three such implements are known from Leicestershire, the nearest to the study © ULAS 2011 3 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) area being from Aylestone (Cooper 2004, 16). There is therefore low potential for a chance find from this period to be present. 7.1.3 The Upper Palaeolithic (c. 40,000-9,700 years ago). The possibility of occupation from this period has been identified recently at Glaston, Rutland where ridge top locations in the east Leicestershire stone belt might be predicted (Colcutt 2006). However the eroded topography of the Lubbesthorpe area would not be conducive to such survival. Between c. 22,000 before present (BP) and 13,000 BP the onset of ice as far as Lincolnshire would have led to the area being uninhabitable. Around 12,600 BP it was re-colonised and the distinctive culture is termed the Creswellian after the cave site in North Derbyshire/Nottinghamshire. There are c. 30 sites in Britain known from this period two of which are from Leicestershire, from Lockington-Hemington and Bradgate Park, Newtown Linford. A change to a more wooded environment in north Europe around 12000 BP is recorded from pollen records and heralds the Final Upper Palaeolithic. This is associated with a distinctive lithic type the convex backed blade and an example is known from Castle Donington. The Terminal Palaeolithic dating from c. 10,300 to 9,700 BP is characterised by ‘long blade’ lithics and an important site was excavated at Launde, Leicestershire (Cooper L. 2006). Although their identification has increased over the past 20 years Upper Palaeolithic sites are still extremely rare and although there are some isolated examples from Leicestershire, there is a low potential for this type of site to be located within the application area, although chance finds may be present (a possible Creswellian core has been located during ongoing (September 2011) fieldwork as a surface find (W. Jarvis and L. Cooper pers.comm.). 7.2 Mesolithic c. 9700-6,000 years ago There are no heritage assets dating to the Mesolithic period recorded from within the application area. However this may be as a result of difficulties in identifying sites of this period. The very small size of diagnostic lithic artefacts for example microliths and bladelets often results in their not being recognised while the more general blade technology, often used as an indicator of Mesolithic activity, also continues into the Neolithic period. Mesolithic material has been located sealed beneath colluvial or alluvial deposits, including an important site at Asfordby (Cooper et al. 2010). Surveys of comparable areas of Midlands lowland sites at Raunds, Northamptonshire and Medbourne, Leicestershire with similar proportions (c. 60%) of glacial drift (boulder clay) indicate that one Mesolithic site may be present on average every 4.85 sq. km and at an average height of 119.2m O.D (Clay 2002, 110). The landscape would have remained basically wooded with some more open land around the streams. The stream valleys in the application area may have potential for the presence of heritage assets of this period. While most of the stream valleys are to be preserved within the green infrastructure appropriate evaluation at full permission stages will be necessary where impacts are identified. 7.3 Earlier Neolithic c. 4,000-2500BC © ULAS 2011 4 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) Evidence of Earlier Neolithic occupation is scarce in Leicestershire and usually only restricted to surface scatters of lithic material. A recent site from Rothley, however, has identified occupation from this period with some possible structural evidence (Speed 2011). From the application area Earlier Neolithic material may be present within an assemblage of prehistoric flint tools, including a blade and scraper (MLE7375) with a further scatter nearby (MLE7376) north of Fishpool Spinney. To the south-east of Fishpool Spinney a scatter of flint tools dated to the Early Neolithic through to the Bronze Age have been discovered (MLE7378). A leaf-shaped arrowhead has been located 200m to the north-east of the proposed M1 crossing access road (MLE7122). Surveys of comparable areas of Midlands lowland sites at Raunds, Northamptonshire and Medbourne, Leicestershire with similar proportions (c. 60%) of glacial drift (boulder clay) indicate that one Earlier Neolithic site is usually located every c. 4.85 sq. km and at an average height of 111.26m O.D (Clay 2002, 81). The Lubbesthorpe landscape would have remained predominantly wooded with perhaps some small cleared areas around possible small settlements suggested by the lithic scatters. The stream valleys in the application area again may have the potential for the presence of heritage assets of this period for example Burnt mounds. While most occupation sites from this period are often only identified from flint scatters ceremonial sites are known from cropmark and geophysical survey evidence. While the lithic scatters around Fishpool Spinney indicate that there is some potential for earthfast heritage assets of this period to be present these are likely to have been eroded by ploughing. While most of the stream valleys are to be preserved within the green infrastructure appropriate evaluation of these and other areas will be necessary at full permission stages where potential impacts are identified. 7.4 Later Neolithic – Earlier Bronze Age c. 2500- 1000BC Evidence of Later Neolithic – Earlier Bronze Age occupation is again usually only restricted to surface scatters of lithic material. Two sites from Rothley, however, have identified occupation from this period with some possible structural evidence (Hunt 2006; Speed 2011). Later Neolithic – Earlier Bronze Age material is also present within the assemblages of prehistoric flint tools, (MLE7375; MLE7376; MLE7378) north and south-east of Fishpool Spinney. To the south-east of Fishpool Spinney a scatter of flint tools dated to the Early Neolithic to Bronze Age have been discovered (MLE7378). Close by is a group of Bronze Age pottery that may suggest an occupation site (MLE6259). A low density scatter of flint tools dated to the Early Neolithic to Bronze Age is recorded immediately to the east of the proposed M1 crossing access road (MLE7385). A Middle Bronze Age palstave was discovered at a site within the north-west corner of the proposed Project area (MLE6268) while a second palstave is recorded (MLE6267) to the east of the proposed M1 crossing access road. To the south of this, close to the site of the Old House, is a ring ditch cropmark, which most likely denotes the site of a Bronze Age barrow (MLE218). A grain rubber is recorded immediately to the east of the proposed M1 crossing access road (MLE8486). Surveys of comparable areas of Midlands lowland sites at Raunds, Northamptonshire and Medbourne, Leicestershire with similar proportions (c. 60%) of glacial drift (boulder clay) indicate that one Later Neolithic – Earlier Bronze Age site may be present on average every 3.64 sq. km and at an average height of 104.26m O.D (Clay 2002, 81). As with the earlier Neolithic period the stream valleys in the application area again may again have the potential for the presence of heritage assets of this period such as Burnt mounds. © ULAS 2011 5 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) While the lithic scatters around Fishpool Spinney indicate that there is some potential for heritage assets of this period to be present these are likely to have been eroded by ploughing. The Lubbesthorpe landscape would have remained predominantly wooded although more permanently cleared land will have begun to develop with some of this perhaps used for pasture around settlements suggested by the lithic scatters. Some as yet unidentified ceremonial and burial areas may be present within the application area. While most of the stream valleys are to be preserved within the green infrastructure some appropriate evaluation will be necessary at full permission stages where potential impacts are identified. 7.5 Later Bronze Age - Iron Age c. 1000 BC - AD 43 Evidence of Later Bronze Age – Iron Age occupation is relatively common in Leicestershire with numerous sites having been identified from developer led work over the past 20 years. Sites of this period have been located on c. 25% of greenfield clayland areas, where no previous archaeological remains were known (Clay 2009). From survey of similar areas later Iron Age sites may be present on average every c. 1.82 sq km (Clay 2002, 81). Sherds of Iron Age pottery were found during fieldwalking close to Abbey Farm (MLE7386). Iron Age coins have been found around 1km to the south-west of the area (MLE8487, MLE9080 & MLE9081). Excavations at Grove Park, which lay around 500m to the east of the area, have revealed a large Iron Age occupation site (Clay 1992, Pollard 1997, Ripper and Beamish 1997; Meek et al 2004; MLE79, MLE112, MLE113). Some of the anomalies identified from the geophysical survey may be evidence for Iron Age enclosures and field systems. Mixed economies with a preference for grassland is suggested from pollen evidence for the Later Bronze age with an increase in arable cultivation into the later Iron Age. A largely cleared landscape with managed woodland is likely to have developed by the time of the Roman invasion in AD43. There is therefore a moderate - high potential for heritage assets of this period to be present within the application area and some appropriate evaluation will be necessary at the full permission stages. (NB This has been confirmed during ongoing trial trenching for the south-east of the application area (W. Jarvis pers. comm.)). 7.6 Roman AD 43-450 Evidence of Roman occupation is again relatively common in Leicestershire although there have been less rural sites located than for the Iron Age, reflecting perhaps more nucleation with fewer larger settlements. Sites of this period have been located on c.14% of greenfield clayland areas, where no previous archaeological remains were known (Clay 2009). The Roman Fosse Way runs south-west to north-east, around 500m east of the area (MLE1380). This is likely to have been a major focus of settlement during the period Excavations on the southern side of Leicester Lane in 2008 revealed Iron Age - Roman boundary ditches, a possible trackway and Roman burials (Harvey 2006; 2009). Inspection during a watching brief on a pipeline trench within the medieval earthworks at Abbey Farm revealed Roman pottery and other possible occupation evidence (MLE219) (Field Archaeology Section Leicestershire Museums 1975). Close to Fishpool Spinney, fieldwalking has revealed pottery and kiln bars dated to the Romano-British period © ULAS 2011 6 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) (MLE84). In the northern part of the area, close to the M69 a Romano-British key tumbler (lock) has been found (MLE9797). There are also several sites dated to the Romano-British period (c. AD 43-410) to the west of the proposed development area. These include a late Roman crossbow brooch found just to the west of Beggar’s Lane (MLE7716), a coin hoard found around 800m to the west of Beggar’s Lane (MLE16619) and a large number of artefacts such as brooches, coins and a mortared floor, suggesting a high status building (MLE5979; Gossip 1997). Further evidence for Roman occupation in this area is also in evidence (MLE8347 & MLE8488). Roman pottery and tile are also known from the area to the east of the proposed development area (MLE223 & MLE7717). Several Roman coins and other metal artefacts have been found in the Grove Park area (MLE7686 & MLE7684). A largely cleared landscape with managed woodland is likely to have continued to develop throughout the Roman period. There is therefore a moderate potential for heritage assets of this period to be present within the application area and some appropriate evaluation will be necessary at the full permission stages. 7.7 Anglo-Saxon 450-850 Evidence of Anglo-Saxon occupation is scarce in Leicestershire and the East Midland in general (Vince 2006). Fieldwalking close to Abbey Farm has produced sherds of Early Anglo-Saxon (c. AD 410-650) pottery, which may be evidence of a settlement site (MLE233). Lubbesthorpe would have continued to develop within the largely cleared landscape with managed woodland throughout the Anglo- Saxon period as settlements begin to lay the foundations for the villages which exist to this day. The Saxon material located near Abbey farm may indicate the earliest origins of the medieval village which was to develop at Lubbesthorpe. There is therefore a low to moderate potential for heritage assets of this period to be present within the application area and some appropriate evaluation will be necessary at the full permission stages. 8. Part 2. Landscape History: Medieval-post medieval 8.1 Aim by Paul Courtney The aim of this section was to use information from the existing desk-top study (Hunt 2008) and other sources to examine the medieval and post–medieval landscape history of the development area, essentially Lubbesthorpe parish and Enderby Hall park. The aim was to draw out the main features of its long term settlement and landscape development and highlight areas of special interest as well as gaps in current knowledge. 8.2 Sources © ULAS 2011 7 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) The study began by surveying the main printed sources. Useful collections of document transcriptions and summaries exist in Nichols (1815, 4i, 37-8) county history and Farnham’s (1933, v, 259-66), Leicestershire Medieval Village Notes. Other documentary sources included catalogues for the Hastings papers (HMC Hastings, 58-61 and 65) and the Duke of Rutland’s archives (HMC, Rutland, iv, 10-11). The patent and close rolls were searched digitally and a few other calendars such as those for inquisitions post mortem manually. The A2A digital facility was used to search for documents in local and national record offices (http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/a2a/) and the Leicestershire Records Office (ROLLR) was visited for a search of its indices and library. In addition documents belonging to Mr Andrew Root, discovered at Yennards Farm were also examined. Useful secondary sources include Fox and Russell’s (1949) study of Leicester Forest, Parker’s (1948) Ph.D thesis on early enclosure in the county, Hartley’s (1989) survey of earthworks in central Leicestershire and the existing ULAS desk-top study by Hunt (2008). A variety of historical maps was used in the process of tying this information together and Google Earth which is now an indispensible tool of landscape research. Unfortunately there was a lack of pre-19th century local maps (see Hunt 2008). 8.3 Descent of Manor 8.3.1 Key references The descent of the manor might at first appear to be only of antiquarian interest but it is vital to understand where documents might be found and also an understanding the pattern of lordship is a key prerequisite to understanding the landscape development. Rather than document every detail, though, the following text will pick out key references. 1086. Domesday manor was part of fee of William Peverell (DB, f. 235b) 1235-6. Eustace Beret (or Barat), a member of the Cantilupe family held a half knight’s fee in Lubbesthorpe from the Peverell fee (BF, ii, 520) 1252. Restitution to William de Cantilupe and his heirs, as their inheritance, of the lands late of Eustace de Cantilupo (presumably Beret) in various manors including Lubbesthorpe (CPR 1247-58, 163) 1268. Millicent Monte Alto (daughter of William de Cantilupe and wife of Eudo de la Zouche) gave rights in Lubbesthorpe to William de la Zouche (presumably a relative, though several candidates) (CIPM, iv, Edw. 1, no. 171). 1284-5. Roger de la Zouche holds manor of Lubbesthorpe from Le Monte (FA, iii, 98) 1302. License by Roger la Zouche, for the alienation in mortmain by him of a messuage, 30 acres of land, 4 acres of meadow, and 26s 8d. of rent in Lubbesthorpe, and two cartloads of brushwood (busce) in the wood of Lubbesthorpe, to a chaplain to celebrate divine service in the chapel of St. Peter’s (the cathedral) in York for the souls of the said Roger, William la Zouche, his father, and Eudo la Zouche and Millicent his wife (CPR 1301-7, 27) © ULAS 2011 8 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) 1303. Roger de la Zouche holds 1/3 of a knight’s fee from William de la Zouche (of Harringworth) of the gift of Millicent Montealto (CIPM, iv, Edw. 1, no. 171; TNA c133/110). 8.3.2 Summary In 1086, the manor of Lubbesthorpe was part of the Peverell fee, centred on Nottinghamshire, created for the Conqueror’s illegitimate son. However, this honour reverted to the crown in the late 12th century. At some point before 1235 the manor was granted by the crown to the Cantilupe family and passed by the second marriage of Millicent Monte Alto (a Cantilupe) to the Zouche of Harringwoth family in the mid-13th century. None of these overlords was based at Lubbesthorpe and may have visited rarely if at all. In 1268 the manor was granted to a lesser line of the Zouche family who held only this manor and dwelt in its manor house In 1303 an inquisition on the death of Roger la Zouche recorded a capital messuage worth half a mark (6s 8d), a garden and curtilage (land around a house) which was worth 4s per annum, a dovecote worth 4s per annum, 100 acres of demesne (belonging to the lord) arable worth 40s, 44 acres of meadow worth 79s 6d, 30 acres of pasture worth 25s, a windmill worth 1 mark (13s 4d) and a wood (boscus) of 100 acres worth 30s. Three free tenants held 3 virgates of land rendered 20s, 15 customary tenants who held one virgate (c. 20-30 acres) each rendered 75s and 13 cottagers 21s-8d. the value of the communal bread oven is illegible but the court was worth 2s per annum (TNA C13/110). The preponderance of virgates suggests that no active land market existed. This may have contributed to the relatively large number of landless or near landless cottagers who presumably worked as wage labourers. 8.3.2 Later History In the late 14th century the manor appears to have been split into three by inheritance; to the St Andrew, Constable and Ashby families, only the last being Leicestershire centred (Nichols 1815, 3i, 37-8; HMC Hastings, i, 59-60; Farnham 1933, v, 264-6). These portions appear to have a complex pattern of inheritance and being leased that is difficult to disentangle especially given no easy access to the Hastings deeds in the Huntington Library. It should also be noted that St John’s Hospital in Leicester had a small holding in Lubbesthorpe (HMC Hastings, i, 60). The Ashby’s seem to the only resident lords and were certainly leasing at least some of the other lands in Lubbesthorpe during the 15th century and may well have been responsible for reuniting the manor. What is especially uncertain, is what role they played in the desertion of the village. Robert Sacherville (or Sackville) was described as of Lubbesthorpe in 1504, and presumably he was living in the manor house, and leasing the manor (Farnham 1933, v, 265). In the reign of Henry VIII, Sir Richard Sacherville purchased the manor of Lubbesthorpe for 300 marks and demised it in his will on his death in 1534 to his godson, Francis Hastings, (later lord Hastings, second earl of Huntingdon) stipulating provision was made for prayers for his soul within the church of St. Peter, Lubbesthorpe. Richard had married Francis’s mother having served Edward Hastings, her first husband, as receiver general as well as being chief steward and forester of Leicestershire for the duchy of Lancaster (Burton 1622 sub Lubbesthorpe; Richards and Everingham 2005, 419; Hill 1875, 227: transcript of will). According to the 1581 survey (Parker 1948, 216-21) the new house at Lubbesthorpe was built by Francis in about 1551 (‘within 30 years last past’). In 1581, Edward Hastings the third earl was in deep debt to the Crown. He arranged an extension of the loan using Lubbesthorpe as surety (Cross © ULAS 2011 9 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) 1966, 77 and 337; ROLLR 5DG/542). This was the context of the royal survey of the manor and house in 1580 (NA:PRO E178/1239 : transcribed by L. A. Parker in his doctoral thesis of 1949, 216-21 ). Burton (1622 sub Lubbesthorpe) adds that the manor was later sold to Sir George Manners of Haddon Hall, Derbyshire, earl of Rutland who already owned adjacent Aylestone. In 1627-8 Leicester Forest was deforested (Nichols 1815, iv, 785 et seq.). 8.4 Problems of sources Lubbesthorpe was a valuable manor, despite being relatively small in size, largely due no doubt to its woodland resources. In 1592 it was worth £400 a year the same as Loughborough cum membris (Cross 1963, 25). As such it is perhaps quite well documented for the medieval period although few post-medieval documents appear to survive. Unfortunately a large collection of relevant documents including 31 deeds dating from 1312-1615 were purchased by the Huntington library in California in 1927 (Cross 1963; Watson 1987) and thus remain relatively in accessible. The deed collection might well shed light on the process of manorial consolidation in the 15th century and the process of desertion. The 1348 indenture (Farnham, v, 262-3) mentioned above is said to have many field names which may provide information on its field system, for instance did it have 2, 3 or 4 fields. One document not seen in the National archives, and probably unsuitable for copying, is a set of depositions from resulting from an enquiry into the bound of the royal forest and Lubbesthorpe manor lands (NA DL 44/924). 8.5 Medieval Landscape 8.5.1 Manor and Chapel complex Lubbesthorpe no doubt had a manor house even by the time of Domesday Book. In 1348 provision was made by Roger le Zouche to provide for his father and mother during their remaining lives including lands, rents and part of the manor site located on the east side of the great gates of manor. Mention is made of a wall of an old grange (barn) by the said gates, the east gable of hall, the orchard the garden and a vivary or livestock house (Farnham 1933, v, 262-3). Around 1550 the manor house was rebuilt in stone with a slate roof over the main building. It and its outbuildings were arranged in a double courtyard plan which can still be seen in the modern Abbey Farm layout, which appears to incorporate at least parts of the 16th century structures (App 1). The main house of two stories appears to have stood on the eastern side of an inner courtyard with a tower at the north end. The footprint of the tower may be the gap between the house and an outbuilding visible in the 1796 print of the chapel (Nichols 1815, 4i, pl. XII). The kitchen appears to have lain adjacent to the house along the southern edge of the inner courtyard. The survey reveals a wide range of outbuildings some arranged into an outer court although its location is not clear from survey alone (App. 1). The chapel appears to be first documented in a charter dated to 1289-96 and was dedicated to St. Peter (HMC Rutland, iv, 10). It was a chapel dependent on the parish church of Aylestone and does not appear to have had burial rights. William Burton (1622, 185) described it as in decay. Nichols (1815, 3i, 38) describes it as ruined and a barn as standing on its site at the end of the 18th century. The 1586 survey describes it as lying outside the two courts, being slate covered and containing 2 bays (App. 1). A 1796 engraving of the chapel shows it as in ruins immediately adjacent to the manor complex, probably to the north-west of the main house (Nichols 1815, 4i, pl. XII) (Fig.2). 8.5.2 Village © ULAS 2011 10 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) In 1086 ten villeins and two bordars (cottagers) are recorded under Lubbersthorpe while two sokemen living in Bromkinsthorpe also held land there. The villeins would have probably held a virgate or standard holding in the fields like the bordars would have mainly survived on wages. In 1303 an extent lists 31 tenants on the manor (TNA C133/110/10). The Lay Subsidy of 1332 records eight taxpayers including the master of St Johns Hospital in Leicester and John ‘le Wodewarde’ paying 19s-11d. In 1377, 17 persons were taxed a sum of 6s 4d in Lubbesthorpe. In 1416 Lubbesthorpe was rated at £1-1s; but in 1446, 6s 8d was rebated, twice the average for the county (Farnham 1933, v, 265-6; Parker 1948, 77-8). A deed of 1422 transferring land in the open fields of Lubbesthorpe lists four persons as being of Lubbesthorpe (ROLLR DE728/542). A further deed of 1471 also mentions land in the field of Lubbesthorpe and involves two persons describes as of Lubbesthorpe (Parker 1948, 77-8 citing Hastings deed in Farnham MS). The 1416 and 1446 tax figures suggest the population of Lubbesthorpe was already in decline demographically. This probably made it susceptible to gradual enclosure by larger farmers as tenancies lapsed. The 1581 survey suggests that Lubbesthorpe was fully enclosed and, apart from some woods, given over to grazing. Twenty closes are named and valued (total £363-13s-4d) but no acreages are given. Interesting names include Millhill Field - valued at £30, West Field pasture-£35 Old Park Pasture-£4 and Thorny Close (with two coppices and the Oxpens)-£20. The Township pasture (valued at £6) may be the site of the former village. Depositions in a 1612 enquiry into forest bounds suggest it had been so for at least 60 years past (Parker 1948, 77-8 and 216-22). The 1666 hearth tax recorded eight persons having 13 hearths between them. In 1722 there were three freeholders polled in the elections and in the 1801 census 81 persons occupying 10 houses recorded (Farnham 1933, v, 266; Nichols 1815, 3i, 38). The post-medieval manor was thus clearly not deserted but a major issue is the date of origin of the scattered farms. The 1666 hearth tax lists both Thomas Wells and Richard Ward as having three hearths, Benjamin Boyer as two and the four other taxpayers had one each. If one of the three hearth households was Lubbesthorpe manor there were probably two tenant farms elsewhere, perhaps the Hatt is a good candidate for one. It is uncertain if the onehearthers were wage-earning labourers or small tenant farmers. Nichols (1815, 4i, 38) records six or seven tenant graziers as living in the manor as tenants of the Duke of Rutland. 8.5.3 Communications. Both Beggar’s Lane (or Moll’s Lane) and the Old Bridle Path could be of some antiquity but it is not possible to date their origin from documentary or topographic evidence. 8.5.4 Woods. Domesday book (f. 235b) records a barren (worthless) wood six furlongs in length by one furlong wide as belonging to the Peverell manor, notionally about 1320 x 220 yards though these were customary measurements which might vary between districts. The reason for the wood being ‘barren’ is unclear, although probably it had been recently felled. The 1322 lay subsidy mentioned John le Woodward as a tax payer. A 13th century deed mentions a tenement as having common rights to wood for repairs, hedging and firewood and in the common wood of Lubbesthorpe (HMC Hastings, i, 59). The royal survey of Lubbestorpe in 1581 mentions diverse and fair young oaks and ashes in several closes as well as plenty of thorns and also two underwoods (coppices) of five years growth and one with no growth. It gives no hint of their specific location other than two coppices were said to lie with the © ULAS 2011 11 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) Oxpens in Thorny close. There was also said to be approximately 300 acres of unenclosed ground within the King’s Forest. 8.5.5 Parks. In 1348 Roger de Zouche grants to his parents for the remainder of their lives various lands and rents including all the ‘ancient park’. In 1354, John of Thoresby the Archbishop of York complained that William de Zouche and others broke into his park in Lubbesthorpe drove away impounded cattle and caused his mowers and reapers to leave his services losing 200 marks worth of crops (CPR 1354-58, 127). Certainly, the previous archbishop was a member of the Zouch family and 30 acres of land and rents in Lubbesthorpe had been granted in 1302 to the cathedral for a chantry (CPR 1301-7, 27). The archbishop may have received the ‘park’ by an unrecorded grant or else its use is just a legal nicety for his 30 acres of demesne, or the 1302 grant may have been made from within the original park, Whatever the issues, they appear to have been resolved in 1361 when confirmation is made of grants by William de Zouche of the old and new parks adjoining the Chase of Leicester to John de Charnel, canon of St Peters (cathedral) in York plus 100s rent and a windmill (HMC Hastings, i, 5960). The 1526 perambulation of the royal forest mentions ‘Lubbster park’ (NA DL39/5/14: I am grateful to Tony Squires for this reference). No more is heard of these two parks until the 1581 survey which records the Old Park pasture. Tony Squires (forthcoming, fig. 7) has plotted the slight archaeological traces of the park. The 1967-8 field name survey by the Women’s Institute recorded a number of relevant ‘park’ field names from an 1870 estate map in private hands. All of these names had disappeared by 1967-8 (ROLLR FNS/101/1, 1A, 2). `The names were: Old Park, Middle Park, Old Park Meadow, Over Old Park and Nether Old Park and all formed a contiguous group (see Figs.1.2 and 4). This area also has little surviving ridge and furrow. 8.5.6 Fishponds and Windmill. The fish ponds are recorded in 1293 when Thomas Winter and others were accused of fishing the ‘stews’ at night and taking fish to the value of 40s and also of breaking the walls of Richard le Zouche’s court (CIM, i , 451). It is unclear if the last two events are related though if so would tend to suggest a now vanished fishpond complex near the manor house. However, Hartley (1989, 58, Fig 65: SK 529 018. HER MLE222) records surviving earthworks as an embanked fishpond which is located to the southern edge of the group of 1870 park field-names (Figs. 1.7 and Figs.3-4). A mill is first documented in 1241 (CRR, 16, nos. 1292 and 1295). In 1348 the manor’s mill was clearly a windmill and it was granted to John de Charnel in 1361 (HMC, Hastings, i, 5960). The 1581 survey mentions a Millhill field amongst the close names. A rather enigmatic bound in 1526 of the Thwaite wood mentions Millhill (Fox and Russell 1948, 84). Its location is far from certain but the rising ground to the west of Hatt Spinney seems a likely location for the windmill (Fig. 1.3). 8.5.7 The Forest Leicester Forest is first recorded in Domesday Book (f. 230a) as the Hereswode which is variously translated as the wood of the army (i.e. the Danish army based at Leicester) or the wood of the community. It is described as the woodland of the sheriffdom in Domesday thus © ULAS 2011 12 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) corresponding to Sherwood (the wood of the shire) in Nottinghamshire. The history of the wood has been discussed in an outstanding topographic study by Levi Fox and Percy Russell published in 1948 although it has few specific source references as it was produced for a general market. Some documents including the decree of inclosure are transcribed in vol 4i (pp. 781-94) of Nichol’s (1815) county history. Control of the forest was assumed by the earls of Leicester after the Conquest. It passed to the Lancastrian family as part of the honour of Leicester later becoming part of the duchy of Lancaster. From 1399 the duchy became a crown estate on the accession of Henry IV. Many of the manors in and around the Forest and the burgesses of Leicester had rights of common within it. The 1526 crown survey reported that few timber trees remained within the royal forest. In 1628 the crown, desperate for cash, deforested Leicester Forest. Under Lubbersthorpe and Aylestone, the Lady Grace Manners received 242 acres and also bought the 123 acres that were allotted to the crown bringing an extra 365 acres to the manor (Fox and Russell 1948, passim). Besides the Thwaite (or Hatt), Fox and Russell (1948, 116) suggested that these lands broadly corresponded with Old Warren and the Lawn farms in the western part of Lubbesthorpe 8.6 Topographic Features of the Forest in Lubbersthorpe The Thwaite was a wood with its own supervisor lying north and east of Lubbersthorpe village. It is first documented in the 14th century and had its own forester and lodge. The 1526 survey describes it as comprising a wood held without common rights. It then comprised a) the Thwaite comprising 114 acres and b) the area known as Enderby Walks which was open to commoners (Fox and Russell 1948, passim). Fox and Russell (1948, 35) suggest that Boyer’s Lodge in Braunstone, a 17th century timber framed house, may have been the site of the medieval lodge, being named after the last keeper of the Thwaite ward. The Hatt Spinney is the last remnant of the Thwaite wood (Fig. 1.3). In 1638 Lady Manners received the ground called the Hatt as part of the forest settlement. The Hatt farm must be another possible contender for the site of the Thwaite lodge as it seems unlikely that the Boyer Lodge (Fig 1.8), now in Kirby Muxloe parish, ever lay within the Thwaite. However, the Hatt farm lies outside the development area and has been destroyed by the construction of the present industrial estate to the east of the M1 (Fig. 1.4). The Lawn or Launde, was part of the forest which took its name from a clearing made to feed deer. It is first documented in 1372. It extended into what is now Enderby parish and included a warren traces of which are still visible west of Beggars Lane in Lubbesthorpe (MLE221; SM30239; Fig. 1.9). A map of c.1600 in the Huntington collection is one of the few surviving maps of the forest and records that the Launde covered 164 acres (Cross 1963, 24). In 1612 part of the Launde was cleared and enclosed (100 acres) to provide an area for driving deer for shooting by stationary archers for a royal visit, although the King never made use of it. An artificial pool was made between the king’s and Lady Manners (Lubbesthorpe) grounds; this has not been located. In 1628 the Launde was split between several adjacent manors. Enderby Warren (Fig 1.1 and Fig.4). This was described as covering two acres in 1526. A 1605 enquiry found it had spread onto common ground (Fox and Russell 1948, 84 and 96). Enderby Park. (Fig 1.5) This park is a landscape park associated with Enderby Hall which stands apart from the site of the medieval manor house in Enderby. The Smith family © ULAS 2011 13 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) acquired the manor in 1695. At the end of the 18th century, Sir Charles Lorraine Smith was living in the hall rather than the manor house which is depicted in Nichols as a Italianate style house in an informal parkland landscape (Nichols, 4i, 136 and pl.XXVIIb). Fox and Russell (1948, 119) ascribe to him much of the planting of woods to the north of Enderby Hall. The Hall has a small 17th century house at its core and appears to have been developed into a substantial residence in several stages from the early 18th century onwards (Pevsner and Williamson 1984, 151-2). The park has no known medieval antecedent and is probably of 18th century origin. It is part of a general informal landscaping of the lands adjacent to the hall incorporating a garden tree-lined carriage way and various woods and spinneys on adjacent tenant land designed to provide a vista from the house and grounds devoid of the poor as well game for sport and pot. The house was also shielded from the quarrying already taking place around the village prior to the 1825 Greenwood map of the county and had expanded to west and south-west of Warren farm by the 1886 Ordnance Survey 25ins to 1 mile map. Warren Farm incorporates the site of Enderby warren within the royal forest prior to 1628 (Fox and Russell 1948, fig: opp 120). Unfortunately there appear to be no estate records for the Smith estate in the public domain. 8.7 Archaeologically Sensitive Sites in the Historic Landscape (i.e c. AD 1000-present) This list is not meant to be comprehensive (see Hunt 2011 for more details), MLE = references to Leicestershire HER (Historic Environment Record) 1). Abbey Farm and adjacent deserted village site SK 541 011 (MLE216), Scheduled Monument SM30274 2). Fishpond adjacent to Old Park area NGR SK 529 019 (MLE 222) 3) 16th century brick clamp NGR SK 544 010 (MLE231) (Hunt 2011, 19) 4) Enderby Hall Park pond NGR SP 539 996 (MLE 105) Rabbit Warren NGR SK 529 018 (MLE 221), Scheduled Monument SM30239 lies just outside outlined development area Farms of Uncertain Age in Development Area All are marked on the 1835 1st edn 1 ins to 1 mile OS map sheet 63 (Names in 1835 in brackets) Hopyard (un-named); New House (Enderby Lodge); Old House (Old Warren); Old Warren (un-named) 9. Conclusion The area of New Lubbesthorpe is in many ways a typical example of a plough-zone lowland Midlands landscape. No in-situ Palaeolithic evidence is likely although isolated artefacts have recently been located be present. Mesolithic activity may be present along the stream sides. Land-use during the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC may include some gradual clearance with limited and isolated prehistoric activity before 1000BC but more evidence is likely for the Iron Age and Roman periods. From evidence located on nearby sites it is likely that the landscape may have been dominated by woodland and pasture in the first half of the 1st millennium BC with more arable cultivation in the later Iron Age (Monckton 2006, 268-70). During the Roman period the land is likely to have been cultivated by communities living in rural settlements associated with the Fosse Way. Boundary systems and burials to the southeast (Harvey 2009) may indicate the presence of settlement between the application area and the river Soar. In common with much of the lowland East Midlands early Anglo-Saxon © ULAS 2011 14 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) material is rare (Vince 2006) although some pottery has been located in the area. By the later Saxon period the settlement patterns indicated in the Domesday survey may have started to be established. The medieval period sees the development of the landscape centred on the village of Lubbesthorpe before its abandonment in the 16th century. In common with much of the East Midlands enclosure established much of the pattern of landscape that exists today with a mixture of arable and pasture fields, small wooded areas and farmsteads. Less typical is its forest-edge position. For a small medieval manor, woodland had an important role in its economy. This contributed to its high valuation in the 1581 survey and the investment in the substantial manor house built in the 16th century. However, like many other Leicestershire manors of small size it was susceptible to desertion and enclosure for livestock farming. Woodland resources were also important to the economy of the earl’s forest which was managed by the duchy of Lancaster in the later Middle Ages as a source of timber, hunting, rabbit warrening and rents. The forest was clearly in decline as a wooded area by the 16th century. It was also an area where the royal woodland was very much dispersed amongst old farming settlements. When it was finally deforested in 1628, Leicester Forest was thus largely split between existing landowners rather than granted in large chunks to royal favourites to build new houses as happened in parts of Northamptonshire or the Dukeries of Nottinghamshire. 10. References Beamish, M. G., 2009 ‘Island Visits: Neolithic and Bronze Age Activity on the Trent Valley Floor. Excavations at Egginton and Willington, Derbyshire, 1998-1999’, The Derbyshire Archaeological Journal 129, 17-172 Bowman, P. and Liddle, P. (eds), 2004 Leicestershire Landsapes. Leicestershire Museums Archaeological Fieldwork Group Monograph 1. Leicester: Leicestershire County Council. Burton, W. 1622, Description of Leicestershire. London. BF Book of Fees. CIM Calendar of Inquisitions Miscellaneous. CIPM Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem. CPR Calendar of Patent Rolls. CRR Curia Regis Rolls. Clay, P., 1992 ‘An Iron Age Farmstead at Grove Farm, Enderby, Leicestershire’, Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society 46, 1-82. Clay, P., 2002 The Prehistory of the East Midlands Claylands. Aspects of settlement and land-use from the Mesolithic to the Iron Age in central England. Leicester Archaeology Monograph 9. Leicester: School of Archaeology and Ancient History, Leicester University. Clay, P., 2009 ‘Finding archaeology on claylands: an inconvenient truth’. The Archaeologist 71 Spring 2009, 26-27. © ULAS 2011 15 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) Colcutt, S., 2006 ‘Appendix 2. Palaeolithic prospection. Some simple guidelines in J. McNabb 2006, 46-49. Cooper, L., 2001 ‘Glaston, Rutland’, Current Archaeology 173, 180–4. Cooper, L., 2002 ‘A Creswellian campsite, Newtown Linford’, Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society 76, 78–80. Cooper, L., 2004 ‘The hunter-gatherers of Leicestershire and Rutland’, in P. Bowman and P. Liddle 2004, 12–29. Cooper, L., 2006 ‘Launde, a Terminal Palaeolithic Camp-site in the English Midlands and its North European Context’. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 72, 53-93. Cooper, N.J.,(ed) 2006 The Archaeology of the East Midlands. An Archaeological Resource Assessment and Research Agenda. Leicester: Leicester Archaeology Monograph 13 Cooper, L., Jarvis., W., and Monckton A., 2010 A Mesolithic station at Asfordby, Leicestershire: Updated Project Design (EH HEEP ref 5899) version 1.1. ULAS unpublished report. Cross, C. 1963, ‘The Hastings manuscripts: Sources for Leicestershire history in California’ Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society. 38, 21-33. Cross, C. 1966, The Puritan Earl: The Life of Henry Hastings Third Earl of Huntingdon 1536 – 1595. London. Farnham, G. T. 1933, Leicestershire Medieval Village Notes, 6 vols. 1928-33. Leicester. Field Archaeology Section Leicestershire Museums 1975 ‘Lubbesthorpe’ in McWhirr, A. (eds.) Archaeology in Leicestershire and Rutland 1975 Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society 50, 60. Gossip, J. 1997. A walkover and fieldwalking survey on the proposed Enderby to Earl Shilton gas supply pipeline. ULAS Report 1997-026. Hartley, R.F., 1989. The Medieval Earthworks of Central Leicestershire. Leicester: Leicestershire Museums, Art Galleries and Records Services. Harvey. J. 2006. An Archaeological Evaluation at the Proposed Aylestone Park and Ride Scheme (Site 35), Leicester Lane, Enderby, Leicestershire (SP 5111 9958). ULAS Report 2006-023. Harvey. J. 2009. Archaeological Excavations on Land Between St John’s/Leicester Lane, Enderby, Leicestershire. ULAS Report 2009-169. Hill, J. H. 1875. The History of Market Harborough. Leicester. HMC Hastings Royal Commission on Historical manuscripts Commision 78, Report on the manuscripts of the late Reginald Rawdon Hastings, Esq., of the Manor House, Ashby de la Zouche, 4 vols. 1928-34. London. © ULAS 2011 16 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) HMC Rutland Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts 34, The manuscripts of His Grace the Duke of Rutland, preserved at Belvoir Castle. 4 vols 1888-1905. London. Hunt, L. 2006. ‘Rothley Lodge Farm’, Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society 80, 237-238 Hunt, L. 2008. An Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment for the Drummond Estate, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 30 and SP 59). ULAS Report 2008-196. TNA The National Archives: former Public Records Office, Kew, London. McNabb, J., 2006 ‘The Palaeolithic’, in N. Cooper (ed.) 2006, 11-50. Meek, J., Shore, M. and Clay, P. 2004 Iron Age Enclosures at Enderby and Huncote, Leicestershire in Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society 78, 1-34. Monckton, A., 2006 ‘Environmental Archaeology in the East Midlands’ in N. Cooper (ed.) 2006, 259-286. Nichols, J. 1815, The History and Antiquities of the County of Leicester. 4 vols in 8. London 1795-1815 Parker, L. A. 1948, Enclosure in Leicestershire 1485-1607, unpublished University of London Ph.D thesis. Copies available in ROLLR and Leicester University Library. Richards D. R. and Everingham, K. J. 2005, Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial And Medieval Families (Royal Ancestry)/ Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company. Ripper, S., and Beamish, M., 1997 ‘Enderby, Grove Park’ in Cooper, N. (ed.) ‘Archaeology in Leicestershire and Rutland 1996’ in Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society 71, 113. ROLLR Record Office for Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland, Wigston. Squires, A. forthcoming, ‘Leicester Forest- its woodland and parks’ in P. Liddle and C. Harman, C., (eds.) Medieval Leicestershire. Glenfield: Leicestershire County Council. Speed, G., 2011 An Archaeological Excavation at Temple Grange, Rothley, Leicestershire. ULAS Report 2011-120. Vince, A., 2006 ‘The Anglo-Saxon Period (c. 400-850) in N. Cooper (ed.) 2006, 161-184. Watson, K. ed. 1987, Henry E. Huntington Library Hastings Manuscripts. London: List and Index Society Patrick Clay Paul Courtney ULAS University of Leicester University Road © ULAS 2011 17 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) Leicester LE1 7RH 29.09.2011 (revised 20.12.2011) © ULAS 2011 18 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) Appendix 1 Summary of survey of house in 1581 after Parker 1948: transcription of NA:PRO E178/1239 (Numbering and comments in italics are by Paul Courtney) 1. House measures 77x23 ft. 2. Hall 53x23 ft (5 glazed windows, each of 8 lights), brick chimney 3. At ‘nether’ (presumably South) end is a buttery (8x24 ft) and a pantry (18x8 ft) Both have a glazed window, pantry window has 8 lights 4. Porch to hall (9x10ft). Room over has closet with 3 glazed windows. (Presumably on east side as kitchen on west) 5. N. end of hall has a tower, 16x16 ft. Pair of stairs leads up toa gret chamber over the hall which has a chnimney , 5 glazed windows (12 lights each). 6. Southward is a withdrawing chamber with 1 window of 6 lights 7. More southward is a bed chamber, 2 windows of 12 lights, a chimney and a little chamber adjoining 8. A garret over the length of the building (presumably excluding tower) with 6 windows. 9. 9. In the tower 14 windows of which 11 are glazed and 3 have six lights. 10. New building covered with slate and (?earlier) tower of lead 11. On west side is a ‘very fair’ kitchen adjoining onto said hall with two ranges and a ‘fair’ lodging over with chimney in it. 12. Larder house at west end of kitchen and two chambers over it with one chimney for lodging clerk of the kitchen and cooks. 13. The kitchen and larder measure 48 x 18ft. and there is also a closet for a spicery. All are covered in slate 14. On the south side of the buttery is annexed a house called the wine cellar. 15. Over the same is a handsome lodging with a little room thereto adjoining also covered with slate. 16. Buildings adjoining to the hall on the north side of the court covered with slate of one story in height wherein are several chambers for lodgings throughout containing in length 144ft in length 18 ft in breadth, being built of ‘stuil and stuil bredth’ = stud and stud breadth set upon stonework. 17. At the entrance to the inner court there is a great gate and covered with slate. 18. 19. Adjoining onto it is a porter’s lodge lofted over ‘of woodwork and runghast’ wherein are lodgings above and beneath all covered with slate. 19. Also in the court next to the kitchen there is a house for any necessary use containing one bay of 18ft in l covered with slate. 20. Also in the garden there is a ‘Stillinge house’ covered with slate of 10 ft in lgth. 21. Also in the outer court there are certain houses covered with straw whereof one is a barn of 4 bays. Also one stable cont 3 bays covered with straw. Also a horse mill with all the furniture thereto belonging. Also another stable at the end thereof called a leantoo. Also a house called the laundry of 4 bays with 23 handsome rooms in the same to dry clothes. And one for the dairy maid. Also a little stable for 4 horses which same houses are covered with straw. Also a chapel standing without the courts -slate covered containing 2 bays. Also there is a house standing further from the house called a slaughter house of 1 bay covered with straw. Also on the south side of the house is a fair plot of ground for a garden with an orchard adjoining- both which parcels contain 1 ½ acres. © ULAS 2011 19 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) 8 9 2 4 3 7 6 1 5 Figure 1 Application Area with features referred to in the text as follows: 1. Enderby Warren . 2. Park Field names (1870). 3. Hatt Spinney. 4. Hatt Farm. 5. Enderby Park. 6. Abbey Farm.. 7. Fishpond identified by Hartley (1989, 58 fig. 65) see Fig. 3. 8. Boyers Lodge. © ULAS 2011 20 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) Figure 2 1796 engraving of the chapel shows it as in ruins immediately adjacent to the manor complex, probably to the north-west of the main Abbey Farmhouse (from Nichols 1815, 4i, pl. XII) Figure 3 Plan of Lubbesthorpe village earthworks (left) and fishpond (see Fig 1.7). From Hartley 1989 Fig. 65. © ULAS 2011 21 Report No. 2011-150 An Archaeological Landscape Assessment for New Lubbesthorpe, Lubbesthorpe and Enderby, Leicestershire (SK 50 & SP 59) Figure 2: Plan of ridge and furrow in the area derived from aerial photography with approx limit of application area outlined. From Hartley 1989 p. 77. © ULAS 2011 22 Report No. 2011-150 Contact Details Richard Buckley or Patrick Clay University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester LE1 7RH T: +44 (0)116 252 2848 F: +44 (0)116 252 2614 E: ulas@le.ac.uk w: www.le.ac.uk/ulas