Vol. 47.4 September 2013 - Society for Ethnomusicology

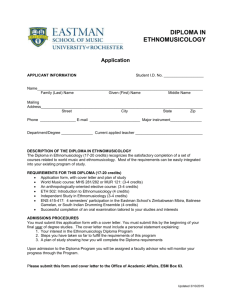

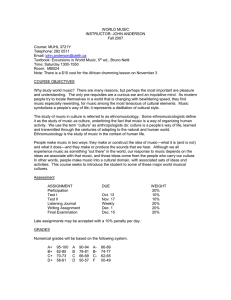

advertisement