369-399 - United Nations - Office of Legal Affairs

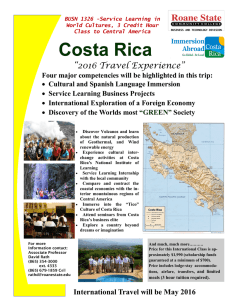

advertisement