Ongoing DOJ Physician Interviews Focus on Buyer Power Issues

advertisement

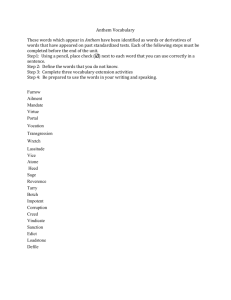

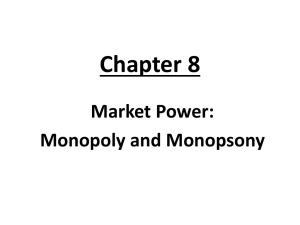

March 11, 2016 Anthem/Cigna; Aetna/Humana: Ongoing DOJ Physician Interviews Focus on Buyer Power Issues; Capitol Forum Analysis Shows Monopsony Enforcement Risk Audio highlights are available here for Policymakers and here for Industry Stakeholders. Investigation Update According to multiple sources, DOJ staff is conducting ongoing interviews with physicians in Anthem/Cigna overlap markets, ranging from doctors in solo practices to those in large medical groups. Interviews have focused on the deal’s potential impact on reimbursement rates, contract terms, and patient quality of care, with DOJ staff in particular querying physicians regarding issues related to care denial, patient access limitations, and networks. These interviews, although wide-ranging, are broadly focused on Anthem’s potential post-merger exercise of monopsony power in the market for purchase of physician services. The Antitrust Division takes monopsony concerns in provider markets extremely seriously, and has enforced on monopsony theories in two prior merger actions. And a Capitol Forum analysis indicates that Anthem, by acquiring Cigna, would account for a share of aggregate provider revenue in many overlap markets well in excess of shares that have driven DOJ enforcement in prior health plan mergers. Specifically, post-merger Anthem would, according to estimates, account for a 40%+ share of provider revenue in 7 markets; a 35%+ share in 16 additional markets, and a 30%+ share in an additional 19 markets. Physician switching costs, as well as potential price discrimination, add to concern surrounding post-merger exercise of monopsony power, and drive real enforcement risk—either through targeted divestitures or, to the extent monopsony concerns are viewed as so broad in scope as to prove unfixable, a full-stop DOJ challenge. In-depth Examination of Health Care Monopsony Issues Monopsony power in markets for purchase of health care provider services—physicians argue deals will drive quantity, quality effects. Through the proposed acquisitions, both Aetna and Anthem will increase their medical memberships substantially—a development that will, by strengthening the payers’ bargaining leverage in provider negotiations, ultimately enable both firms to drive reimbursement rates to physicians and hospitals lower. Buyers, of course, are legally permitted to make acquisitions that would have the effect of lowering their input costs. However, when a merger positions a buyer to depress input prices below competitive levels, it involves the creation of monopsony power—a violation of Clayton Act Section 7. According to deal opponents, at least some large insurers already exercise monopsony power over smaller providers. “What we’re hearing from many of our practices around the country is that there are payers coming to them offering them rates below even their costs,” says Wanda Filer, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians. The exercise of monopsony power may have the impact of reducing quantity of output, degrading quality of output, or both. In the health care context, although monopsony rates are relatively unlikely to depress physician output in the very short-term, in the medium to long-run, physicians may exit (or choose not to enter) the market 1 You are a subscriber to The Capitol Forum. Please contact 202-601-2300 for editorial or sales questions. © 2016 by The Capitol Forum. Direct or indirect reproduction or other distribution of this article without prior written permission from The Capitol Forum is a violation of Federal Copyright Law. in response to sub-competitive reimbursement. “If these family practices are unable to make ends meet that’s problem for that community—if the message gets out to students that’s a problem for workforce,” Filer explains. Although driving output to sub-competitive levels is the most common effect of monopsony, physicians groups have heavily emphasized a second potential monopsony effect of the proposed Anthem/Cigna and Aetna/Humana mergers—a reduction in quality of physician services, and concomitant degradation in patient quality of care. To the extent reimbursement rates fall below competitive levels, physicians are incented to replace lost revenue through increased patient volume. When physicians spend less time with patients, however, worse patient health outcomes, for example, missed ailments or diagnoses, are very likely to follow. And aside from physician access issues, doctors groups contend that monopsony payment rates would leave physicians unable to invest in equipment, training, and hiring—all investments that would, in the long-term, be expected to improve patient quality of care. Given the nature of potential harm, physicians’ arguments regarding patient care quality and access may prove uniquely compelling, from both enforcement and political perspectives. “Because we’re dealing with health care access, and not buying a sink or a car it makes it even more problematic—these are often times life or death decisions,” notes Matthew Katz, the Connecticut State Medical Society’s executive vice president. Anthem/Cigna estimated provider revenue shares in at least 42 markets raise potential monopsony concerns. In the health care context, DOJ has enforced on monopsony theories at relatively low buy-side shares. In challenging UnitedHealth/PacifiCare (2005), for example, DOJ alleged that UnitedHealth would be positioned to exercise monopsony power with a revenue share in excess of 35% in Tucson and 30% in Boulder, “for a substantial number of physicians”—a qualifier indicating that post-merger United’s MSA-wide revenue shares would likely have been even lower than 35% or 30%. Although DOJ’s Aetna/Prudential (1999) complaint does not identify provider revenue shares, in the output market, post-merger Aetna would have enrolled 63% of HMO/HMO-POS members in Houston, and 42% in Dallas. However, because physicians generate revenue from both non-HMO commercial plans as well as government payers, Aetna’s post-merger revenue share of physicians’ services likely fell substantially below these numbers. In fact, in a in a 2009 journal article, Bates White LLC economist Cory Capps suggested that Aetna’s post-merger buy-side patient share may have been as low as 25% in Houston, and 15% in Dallas. According to a Capitol Forum analysis, in a substantial number of geographic markets, a combined Anthem/Cigna would account for provider revenue shares above those that have driven monopsony enforcement in past health plan mergers. Unsurprisingly, markets with greatest buy-side concentration are located in Anthem Blue states, and include MSAs in Connecticut, Georgia, Indiana, Maine, New Hampshire, and Virginia. As the table below demonstrates, post-merger Anthem would, according to these estimates, account for a 40%+ share of provider revenue in seven MSAs and, in an additional 16 markets, a 35%+ provider revenue share. Markets MSA Indianapolis Dalton State IN GA Commercial Market HHI Commercial Share Estimate Provider Revenue Share Estimate Pre-Merger Post-Merger 3,299 5,716 3,340 5,924 AVG 71.6 73.9 ANTH/CIG 46.1% 43.2% 2 You are a subscriber to The Capitol Forum. Please contact 202-601-2300 for editorial or sales questions. © 2016 by The Capitol Forum. Direct or indirect reproduction or other distribution of this article without prior written permission from The Capitol Forum is a violation of Federal Copyright Law. Rochester Terre Haute Manchester Richmond Lafayette Anderson Hartford New Haven Waterbury Kokomo Bridgeport Nashua Danbury Bangor Lynchburg Fort Wayne Danville Portsmouth Michigan City Lewiston Norwich NH IN NH VA IN IN CT CT CT IN CT NH-MA CT ME VA IN VA NH-ME IN ME CT-RI 2,808 5,436 2,683 3,514 2,780 4,803 2,426 3,139 3,108 3,764 2,442 2,384 2,355 2,884 4,484 3,595 7,177 2,733 4,064 3,234 3,121 4,354 7,047 4,215 5,241 4,762 6,073 3,783 4,440 4,403 5,191 3,723 3,640 3,591 4,427 5,436 4,762 7,724 3,940 5,135 4,597 3,921 59.2 66.0 57.9 63.1 64.6 60.6 55.8 55.7 55.6 60.4 54.3 53.8 53.5 60.1 54.8 56.1 54.1 54.1 55.5 58.0 48.7 43.1% 42.6% 42.2% 42.1% 41.6% 39.0% 39.0% 39.0% 38.9% 38.9% 38.0% 37.8% 37.4% 36.7% 36.5% 36.1% 36.1% 36.1% 35.8% 35.4% 35.2% In an additional 19 markets, the combined firm would account for a 30% aggregate provider revenue share, including Gary, IN (34.9%), Evansville IN-KY (34.6%), Winchester VA-WV (34.4%). Elkhart-Goshen, IN (33.9%), Roanoke, VA (33.6%), Blacksburg-Christiansburg-Radford, VA ,(33.6%), Harrisonburg, VA (33.0%), Hinesville-Fort Stewart, GA (32.6%), Fort Collins-Loveland, CO (32.3%), Grand Junction, CO (32.2%), Columbus, GA-AL (31.7%), Bowling Green, KY (31.6%), Albany, GA (31.5%), Portland-South Portland, ME (31.4%), Valdosta, GA (31.3%), Owensboro, KY (31.0%), Savannah, GA (30.4%), Warner Robins, GA (30.4%), and Greeley, CO (30.3%). And in 22 additional markets, post-merger Anthem would account for a 25%+ share of provider revenue. The provider revenue analysis utilizes American Medical Association estimates of combined Anthem/Cigna MSA-level HHI, and merger-driven change in HHI, in combined HMO+PPO+POS markets—effectively, all commercial insurance. Using HHI numbers, we calculated all-commercial market share estimates, which were then weighted to account for the fact that providers generate revenue from non-commercial payers, primarily Medicare and Medicaid. Finally, in order to more accurately project aggregate revenue shares, the numbers were weighted to reflect the fact that Medicare and Medicaid reimburse providers at sub-commercial rates. Note that, in the analysis, payer category is not weighted by consumption. So, for example, although Medicare patients typically consume health care services at an above average rate, the provider revenue share estimates assume that in Indiana, where Medicare covers 15% of residents, Medicare patients account for 15% of Indiana 3 You are a subscriber to The Capitol Forum. Please contact 202-601-2300 for editorial or sales questions. © 2016 by The Capitol Forum. Direct or indirect reproduction or other distribution of this article without prior written permission from The Capitol Forum is a violation of Federal Copyright Law. provider services rendered. At the same time, uninsured patients, who account for 11% of Indiana residents, consume provider (and, specially, physician) services at a below average rate, but are assumed to account for 11% of provider services rendered. Notably, the combined Aetna/Humana would have relatively lower shares—in only two markets, Rockford, Illinois (25.8%) and Springfield, Ohio (25.5%), would the combined firm account for a 25%+ share of aggregate provider revenue. That said, the analysis likely marginally understates Aetna/Humana’s provider revenue shares, given that, in many overlap markets, Aetna/Humana account for some percentage of provider Medicare payments. However, because about 70% of Medicare business is traditional Medicare—even in a market in which Aetna/Humana enrolled 33% of Medicare Advantage members, the firm would account for just 10% of Medicare payments. So, for example, in Illinois, where 14% of the population is covered by Medicare, about 4.2% of the population is enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan, and, assuming a 33% state-wide share, just 1.4% in an Aetna or Humana MA plan. Aggregate shares may understate potential monopsony effects—switching costs; substitutability of government payers. In addition to aggregate revenue shares, two important input market characteristics may drive heightened monopsony concerns in the health care provider context. The first involves physician switching costs, or, put differently, a physician’s costs to replace lost patients. In the event a managed care organization terminates a physician contract, the physician may be able to replace a small percentage of lost patients with negligible disruption, by filling from a patient backlog, or short-term timeshifting. Above a certain threshold, however, because a physician cannot replace a substantial number of patients immediately, the physician will face the prospect of real, and irreplaceable, lost income. This is a function of that fact that physicians’ time cannot be stored—if a physician spends weeks or months operating below capacity, that income is lost forever. Furthermore, because lost patients cannot be replaced immediately, a physician’s cost to replace, for example, 40% of their practice’s patients may be more than double the cost of replacing 20% of patients—put differently, a physician’s lost income may increase more than proportionally with the number of patients they must replace. In fact, this argument was a key driver of the Division’s 1999 Aetna/Prudential challenge, explains Georgetown University economics professor Marius Schwartz, who served as the Antitrust Division’s Economics Director of Enforcement at the time the complaint was filed. “The key idea was that it gets progressively harder—if you have to replace twice as many patients it costs you more than twice than if you had to replace half the patients,” says Schwartz. This is, notes Schwartz, a function of the fact that physicians typically incur a delay in replacing patients—"if you have to replace more patients you have to wait a longer time until you do the full replacement because patients don't all arrive on the same day— they arrive over time," Schwartz explains. In addition to the timing issue, commercial payers’ potential monopsony power is strengthened by the fact that Medicare and Medicaid patients do not represent, from a revenue perspective, a full substitute for commerciallyinsured patients. “You’re not replacing equivalents—you’re replacing patients where you get payments at a much higher amount with patients where reimbursement is significantly less,” says Neil Kirschner, a Senior Associate of Health Policy and Regulatory Affairs at the American College of Physicians. 4 You are a subscriber to The Capitol Forum. Please contact 202-601-2300 for editorial or sales questions. © 2016 by The Capitol Forum. Direct or indirect reproduction or other distribution of this article without prior written permission from The Capitol Forum is a violation of Federal Copyright Law. Given relatively lower government reimbursement rates, a physician would need to attract, for example, multiple Medicaid patients in order to replace revenue from a single lost commercially insured patient—a prospect that makes patient replacement even more difficult. And, when measured by lost variable profits, arguably the more relevant metric when measuring potential monopsony power, the government/commercial patient replacement ratio increases even further. Aggregate shares may understate potential monopsony effects—price discrimination. The fact that some providers are relatively more dependent on a certain payer’s patients, and commercial payers’ resulting ability to price discriminate in provider contract negotiations, may also enhance potential exercise of monopsony power. For example, a combined Anthem/Cigna would account for a roughly 42.2% aggregate provider revenue share in the Manchester, New Hampshire MSA. This share, however, will vary by individual practice—post-merger Anthem may, for example, account for 32.2% of one provider’s revenues, but 52.2% of another’s. This varying provider dependence provides a mechanism for price discrimination, through which Anthem may target dependent providers for lower rates. Potential price discrimination likewise played an important role in the Division’s 1999 Aetna/Prudential challenge. “If the insurer perceives that a particular physician group is more vulnerable post-merger, it may be able to impose lower reimbursement rates than if it has to do it market-wide” says Schwartz. “The unit of analysis was more granular—you don’t just look at all the physicians in Houston—you have to look at it more practice-bypractice.” Of course, aggregate market-wide market shares are nonetheless important in monopsony analysis, as they affect a provider’s potential replacement rate—higher Anthem market-wide shares mean the pool of non-Anthem replacement patients is much smaller, and the task of replacing lost patients more difficult. At the same time, however, the potential for price discrimination means that MSA-wide aggregate market shares almost certainly understate Anthem’s ability to depress reimbursement rates to at least some targeted physicians. Arguments against buyer power—new demand; PPOs. In the face of these switching costs and price discrimination arguments, Anthem will contend that, for a number of reasons, its Cigna acquisition will not actually create or enhance monopsony power. Although these arguments run the gamut, many rely on changes in the health plan marketplace since DOJ’s prior monopsony enforcement actions—especially changes wrought by the ACA. A first involves the argument that switching costs, or costs to replace patients, are overstated, given the ACAdriven coverage expansion and accompanying new demand for health care services. This new demand, coupled with a short-term Medicaid fee bump that states including Indiana and Connecticut have implemented, could mean that physicians’ cost to replace commercially-insured patients may have decreased. In addition, the ACA’s Medical Loss Ratio requirements may, to some extent, limit insurers’ expected gain from the exercise of monopsony power. Although not directly ACA-related, the relative growth of PPO and POS plans, through which insurers offer members some coverage for out of network provider services, may enable a physician to capture revenue from existing patients even if they exit a payer’s network. Physicians may also re-capture lost patient revenue by excluding third-party payers altogether through, for example, direct primary care or concierge practices. As a 5 You are a subscriber to The Capitol Forum. Please contact 202-601-2300 for editorial or sales questions. © 2016 by The Capitol Forum. Direct or indirect reproduction or other distribution of this article without prior written permission from The Capitol Forum is a violation of Federal Copyright Law. result, even if a managed care organization terminates a physician contract, the physician is unlikely to actually lose 100% of the payer’s patients (or revenues) in question. Existing provider market power may limit hospital services monopsony concerns. Recent marketplace developments aside, Anthem’s increased post-merger enrollment, and bargaining leverage, would almost certainly lead to lower reimbursement rates for many physicians, physicians groups, and hospitals. An additional key argument for the parties, however, is that, for many providers, this outcome is unlikely to actually reflect the exercise of monopsony power. This argument rests on the fact that, in order to exercise monopsony power, a buyer must depress rates, or input prices, below competitive levels. “In the true monopsony model, the suppliers are competitive, they’re just making a competitive rate of return and where you have a dominant buyer facing them, you can have a variety of adverse consequences,” explains John Kirkwood, a professor of law at Seattle University, and author of a number of widely-cited law review articles on monopsony power. By contrast, notes Kirkwood, when suppliers already enjoy some degree of market power, an increase in buyer leverage may simply bring a supplier’s prices closer to a competitive level—an outcome that represents countervailing, rather than monopsony, power. Especially given aggressive consolidation over the last two decades, many hospital systems today almost certainly enjoy some degree of market power. And even some specialty practices, to a lesser extent, may benefit from supracompetitive rates, given their scarcity relative to primary care physicians. To the extent Anthem is positioned to depress hospital and specialty reimbursement rates, then, it may simply push rates closer to competitive levels—an outcome that would not, in and of itself, represent the exercise of monopsony power. DOJ typically skeptical of countervailing power arguments. The parties’ countervailing power argument is especially important, given that if Anthem realizes increased provider discounts post-merger, the firm’s selfinsured customers, who pay claims directly, will therefore benefit directly. In fact, the expectation that Anthem will exercise countervailing power in negotiations with dominant hospital systems post-merger is a primary reason that many large self-insured customers view the firm’s Cigna acquisition as a neutral, or even positive, development. At the same time, however, ASO is only one health plan segment, and Anthem’s fully-insured customers are relatively less likely (and, if the empirical evidence is predictive, very unlikely) to benefit from pass-through provider discounts. That said, antitrust enforcers are generally skeptical of countervailing power justifications. And in fact, in November 13 remarks to a health care industry conference at Yale University, Antitrust Division chief Bill Baer sounded a skeptical note on such arguments, emphasizing that “[c]ourts have long rejected the notion that ‘countervailing market power’ justifies anticompetitive mergers or agreements....[c]onsumers do not benefit when sellers – or buyers – merge simply to gain bargaining leverage.” In short, Anthem’s ability to exert countervailing power in the purchase of hospital services, even with some consumer pass-through, is unlikely to outweigh the possibility that post-merger Anthem could exercise monopsony power in markets for the sale of, for example, primary care physician services. “Family practitioners run at lower margins than certain specialties, particularly if they’re in solo or small group practice, so trying to accommodate lower reimbursement is going to be very difficult for them,” explains Mike Jurgensen, the Medical Society of Virginia’s Senior Vice President of Health Policy and Planning. “They don’t have any leverage now, they’d have even less later.” 6 You are a subscriber to The Capitol Forum. Please contact 202-601-2300 for editorial or sales questions. © 2016 by The Capitol Forum. Direct or indirect reproduction or other distribution of this article without prior written permission from The Capitol Forum is a violation of Federal Copyright Law. Parties pitch countervailing power; scale as accelerating ACA reforms. Even to the extent DOJ concludes that countervailing power is not a pro-competitive justification for either merger, the parties publicly argue that consolidation will actually accelerate the implementation of ACA-driven political and public policy goals— specifically, delivery system reform through value-based payment models. Value-based reimbursement, of course, is nearly universally recognized as a more cost-efficient, and ultimately outcome-improving, delivery system than traditional fee for service, and its implementation is viewed as something of a legacy issue for the Obama Administration. And countervailing power over dominant providers, coupled with enhanced scale, argue the parties, will speed the shift to value-based reimbursement provider contracts. A related point involves the argument that, due to ACA-driven changes to reimbursement models, concerns around monopsony power have become less relevant. Through various mechanisms, including Accountable Care Organizations, the ACA incents payers and providers to work collaboratively, sharing both risk and profit margin. Given the incentives for partnership, the argument goes, the new system is much less adversarial, and a payer has no business incentive to drive reimbursement rates below competitive levels—as providers will instead simply opt to collaborate with other payers. Deal opponents, however, argue that increased insurer buyer power would actually impair the ACA’s goals by, for example, preventing physicians from investing in practice transformations, including electronic medical records and care coordinators, that the ACA encourages. And, of course, given new ACA-created demand, a situation in which medium or long-run supply of primary physician services declined, would lead to access and wait time issues the ACA’s architects would certainly hope to avoid. In short, given pushback not just from the American Hospital Association and American Medical Association, but also national primary care groups, state-level medical associations and individual physicians, arguments around monopsony power as less relevant in a post-ACA world ring somewhat hollow. “I suppose there’s a kernel of truth in there, in that the Affordable Care Act does try to incent new payment systems but if you look at who’s opposing these mergers, it looks like the upstream providers don’t buy the argument,” concludes Kirkwood. Issue Snapshot Outlook: Market Consensus of 48% is Reasonable Reasons for Challenge/Collapse Most Compelling Narrative In 10 of 14 overlap states, the combined Anthem/Cigna would enroll 50%+ of ASO members. ASO plans sold to self-insured employers are likely a properly defined product market, and any deal to create a firm with a 50%+ share in any properly defined product market is likely to draw an agency challenge. Problematically, the ASO overlap, for a number of reasons, does not appear amenable to a divestiture solution. In addition, the transaction appears to raise real, and wide-ranging, monopsony Reasons for Merger Clearance Most Compelling Narrative In the sale of ASO plans to self-funded employers, whether national accounts or single-site large groups, Anthem will face continued competition from United and Aetna, as well as, in some locations, strong regional players. Furthermore, due to growth in unbundling and private health insurance exchanges, the sale of ASO plans to self-funded employers may not constitute a properly defined relevant product market. Regardless, runner-up bid data may demonstrate that Anthem and Cigna do not compete particularly closely self-funded 7 You are a subscriber to The Capitol Forum. Please contact 202-601-2300 for editorial or sales questions. © 2016 by The Capitol Forum. Direct or indirect reproduction or other distribution of this article without prior written permission from The Capitol Forum is a violation of Federal Copyright Law. issues in markets across the country. Especially given significant DOJ and political scrutiny around health insurer consolidation, these harms to competition could be sufficient to draw a full-stop DOJ challenge. business employers, who, importantly, are oftentimes sophisticated, powerful buyers. And brokers and customers in Anthem/Cigna overlap states generally view the deal as competitively neutral at worst, and in some instances, actually likely to drive lower prices and broader access. Competitive Analysis -Self-insured employers are unlikely to view fully insured plans, private exchanges, or unbundling as plausible alternatives to contracting with Anthem or Cigna. Put differently, there may be a properly defined market for sale of ASO plans to self-insured employers, in which the Anthem/Cigna deal would increase concentration significantly, and position Anthem with a 50%+ share in 10 of 14 overlap states. Competitive Analysis -Self-funded employers may be positioned to defeat a price increase through a number of means, including unbundling (using an independent TPA for administration) or implementing a multi-carrier private exchange. -Harm in the market for ASO plans sold to selfinsured employers appears difficult to remedy through behavioral or structural fixes. -Post-merger Anthem would account for an estimated 35%+ aggregate provider revenue share in at least 23 MSAs—a post-merger share sure to drive monopsony concerns—especially given switching cost and price discrimination issues. -Although monopsony issues may be addressable through targeted structural remedies, the potentially broad scope of harm leads to the prospect that DOJ could opt for a full-stop challenge instead. -Even in non-overlap states, given Anthem’s membership in the BCBSA and BlueCard program, it is not clear that Anthem is incented to use the Cigna brand to aggressively compete head to head with non-Anthem Blues. Put differently, the deal could lead to diminished competitive intensity even in non-overlap markets, or even strengthen nonAnthem Blues’ dominant positions in certain markets. Political and Other Factors -Health insurance mergers have traditionally faced a very high level of DOJ scrutiny, and post-ACA, this -Runner up bid data may show that Anthem and Cigna, given their different competitive strengths, are unlikely to be self-funded employers’ first and second choice ASO plans, rendering post-merger unilateral effects relatively less likely. -The combined firm’s share of ASO lives in overlap markets notwithstanding, customers and large group brokers largely view the deal as likely to drive neutral, or even favorable, pricing effects. -Despite the BCBSA rules, Anthem may show that the Cigna acquisition would drive a competitively neutral, or pro-competitive outcome in the firms’ 36 non-overlap states. -The deal may broaden access, or, perhaps more importantly, drive system-wide health care costs lower—especially to the extent the merger can accelerate the transition to value-based reimbursement models. To the extent the parties can convincingly win this argument, monopsony concerns may fall by the wayside. Political and Other Factors 8 You are a subscriber to The Capitol Forum. Please contact 202-601-2300 for editorial or sales questions. © 2016 by The Capitol Forum. Direct or indirect reproduction or other distribution of this article without prior written permission from The Capitol Forum is a violation of Federal Copyright Law. scrutiny is likely to increase even further. DOJ leadership has frequently warned against any insurer consolidation that would threaten the ACA’s goals. -The deal faces significant interest group opposition, with the politically powerful American Medical Association and American Hospital Association the deal’s most vocal critics. National provider groups, and state-level medical associations, as well as the American Antitrust Institute and Center for American Progress have expressed opposition to the deal as well. -State-level insurance commissioner review (the deal requires approval in 26 states) represents an additional layer of risk. -Democratic presidential front-runner Hillary Clinton has expressed “serious concerns” about the Anthem/Cigna deal—a statement that provides additional political cover for a challenge, and is sure to embolden political and consumer opponents. Timeline -July 24, 2015—deal announcement. -September 28, 2015—both parties receive DOJ second requests. -The parties certified compliance with DOJ’s second requests in early February. -The parties expect the deal to close in H2 2016. -The merger agreement sets an outside date of January 31, 2017, although either party may extend this date to April 30, 2017 if the only outstanding condition to close involves receipt of governmental/regulatory clearances. 9 You are a subscriber to The Capitol Forum. Please contact 202-601-2300 for editorial or sales questions. © 2016 by The Capitol Forum. Direct or indirect reproduction or other distribution of this article without prior written permission from The Capitol Forum is a violation of Federal Copyright Law.